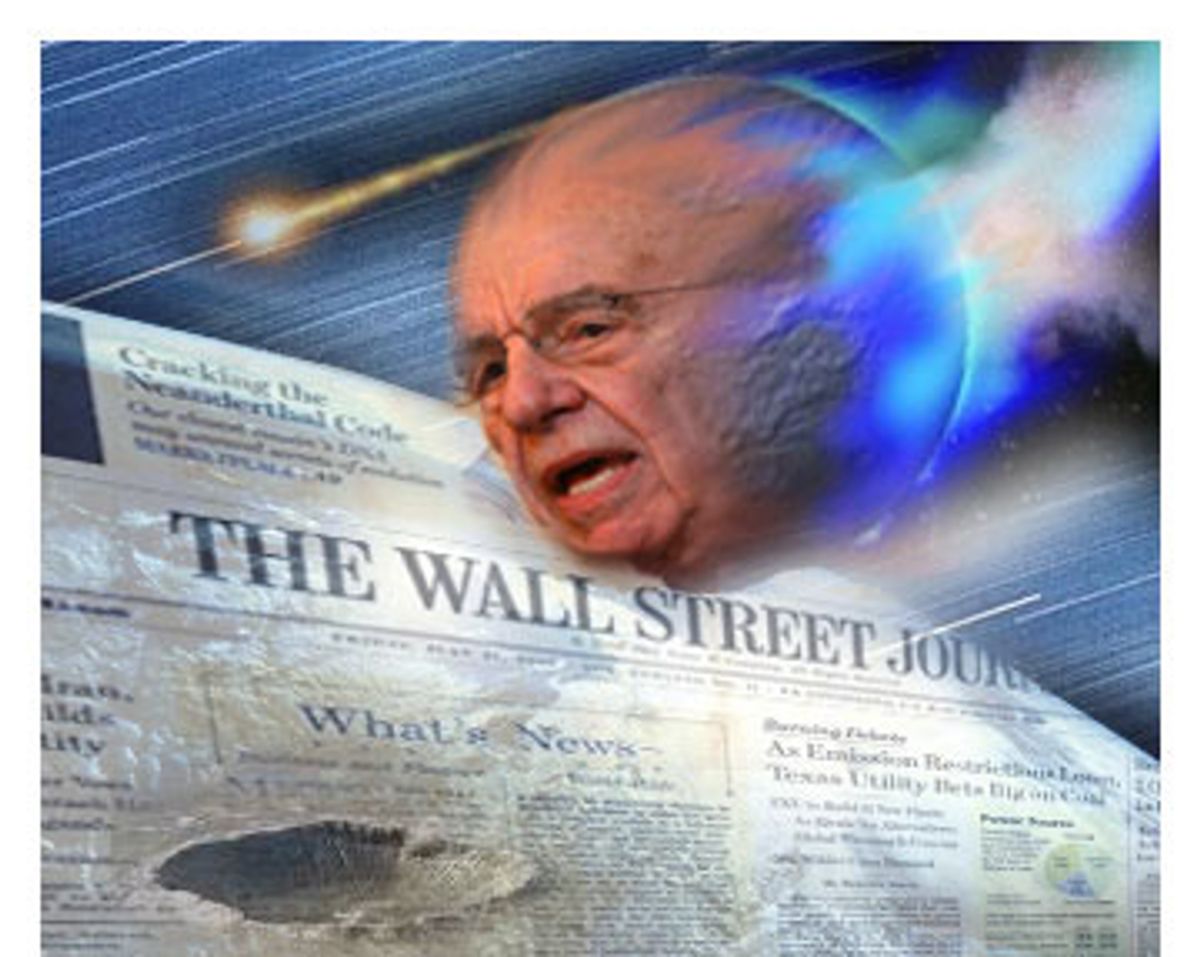

Imagine an asteroid plummeting toward Earth. You are an astrophysicist, so you have done the calculations. You know the trajectory and azimuth and mass of the thing, and you know that this speck in the sky will soon be turning all of humanity into carpet sweepings.

That describes the predicament facing the reporters and editors of Dow Jones & Co., publishers of the Wall Street Journal, as they watch asteroid Rupert Murdoch stream their way. The mogul is offering $5 billion to make Dow Jones part of his News Corp. media empire, sandwiched somewhere between the New York Post and "The O'Reilly Factor." While the rest of the world struggles to make sense of that dark blotch in the sky, these unemotional business and financial reporters have it all figured out. They know what's going to happen because they cover this kind of thing all the time -- stodgy, family-owned, "mature" businesses about to be made more "efficient" and "lean," all in the name of God, country and shareholder value.

They know that it is Dow Jones' turn to be put on the Shareholder Value Slim-Fast diet. With 52 percent of the voting shares opposing the merger, that means that just 3 measly percentage points stand between Murdoch and his prize. The sheer power of his money is very likely to pull in the shares that he needs. And Wall Street expects the Dow Jones board of directors to fall in line. As CNBC's Jim Cramer put it, "They are not on the board to protect the newsroom. They are on the board to assess whether Dow Jones can get to $60 on its own at some time in the future without the Murdoch bid."

The reporters at Dow Jones know that you can forget about all the spin you see from the Murdoch camp -- about how he will continue the Journal's lofty journalistic traditions and how he beefed up the foreign bureaus of the Times of London when he took over that paper. If and when Murdoch gets Dow Jones he is going to make money on it, and that will require drastic cutbacks -- entire "inefficient" divisions shuttered, employees thrown into the streets. Employee union negotiators, who had thought current management was hardheaded, are likely to look back on the pre-Murdoch days with nostalgia. "He's paying 40 to 50 times earnings, and he is going to get a return on that. He is going to crank down on costs," said one longtime Dow Jones journo who knows his way around a balance sheet.

And why not? Dow Jones opened the door to Murdoch -- or anyone with sufficient bucks to buy the company -- when it became a public company in 1963.

The Murdoch-Dow Jones face-off is only the most dramatic illustration of what has been obvious for a long time, which is that public ownership and newspapers do not mix. Investor interests can be balanced against the interests of journalism, and compromises in either direction can be rationalized, but at bottom it is an irreconcilable conflict in which journalism will always lose.

Public ownership has been a disaster for newspapers not just because it invites hostile takeovers. Quite simply, much of what newspapers do has no clear investment rationale. Entire segments of the business -- such as foreign bureaus and investigative reporting -- are inimical to profitability, particularly when viewed on the quarter-by-quarter basis favored by Wall Street. Cramer nailed down the shareholder value view of the newspaper biz a few weeks ago, when he said, "These are diminishing assets. They don't need to exist. Younger people rarely read them."

Cramer is not wrong or cynical; he is simply being realistic and refreshingly free of hypocrisy. Viewed from a shareholder value perspective, the newspaper business is a dinosaur. And that is why the shareholder point of view needs to be eliminated from the newspaper business. The shareholders, not the newspapers, are the ones who don't need to exist.

A free press has a purpose in society. Shareholders, bless their hearts, deserve to make money without being screwed. But they should find another way of turning a profit. Columbia Journalism Review put the case against public ownership mildly in a recent editorial, saying, "Public ownership of newspapers no longer makes the kind of sense it made when the industry was rapidly shedding labor costs thanks to new technology, and when the money that stockholders poured in was invested partly in editorial."

This is not to say newspapers don't benefit from infusions of capital and fresh ownership at the top. The Hartford Courant is, in many respects, a better paper now than it was when I worked there in the 1970s, before it came under Times Mirror (now Tribune Co.) ownership. But the same cannot be said for the Norwich Bulletin, which was stripped of its distinctive local character after being bought by the Gannett chain, publisher of USA Today and other, less glorious properties. A newspaper that once presented dull but exhaustive coverage of local news has been homogenized, stripped of individuality and turned into a wire-service-dominated McPaper.

While it's true that today's Courant is always in the running for top awards, it has lost much of its down-home spirit. When I began working there, in a long-disbanded bureau next to a riverfront bar in a smelly section of Groton, Conn., I produced three to four daily articles of local interest to the Courant's readers in nearby New London -- all 650 or so subscribers. That would have been an insane waste of shareholder resources for a public company. But the Courant didn't worry about that. It was privately owned. Covering New London and other low-readership towns was viewed by management as a duty for a statewide newspaper.

My competitor in New London was a feisty little paper called the Day. It is still one of the best small newspapers in the country because it has not been gobbled up by a chain, and it has not been gobbled up by a chain because it is owned by people who don't have to answer to shareholders. It is owned by a public trust established by the man who ran the paper from 1891 until his death in 1938, an immigrant from Düsseldorf, Germany, named Theodore Bodenwein. Bodenwein was no Joseph Pulitzer. "He emphatically opposed muckraking, which he felt was unnecessary and out of character for a small New England city," observed Gregory Stone in his book, "The Day Paper," about the independent newspaper. But the ownership structure Bodenwein created means that New London will always have a competent, non-chain-owned newspaper devoted to covering southeastern Connecticut.

So while the Courant folded its New London-Groton bureau, and the Norwich Bulletin was Gannett-ized, the Day, heedless of profit motives, has continued to do a great job as a useless, doesn't-need-to-exist newspaper.

The Day used to be the rule, not the exception. Newspapers were operated by public-spirited families like the Bodenweins and the Sulzbergers and the Bancroft clan that owns most Dow Jones shares. The latter, unlike the Sulzbergers, had no role in the operation of the paper -- a hands-off attitude that Dow Jonesers will, I am sure, miss greatly once they enter the Murdoch era. With a few isolated exceptions, the families have long since sold out and their successors have surrendered to the number crunchers, because numbers are all that matter to a public company.

Take a look at the Los Angeles Times, which cut its staff by almost 6 percent, or 150 persons, last month. Or the Chicago Tribune, which is cutting its staff by 3 percent, or 100 employees. But even drastic cuts like those are not enough to satisfy the Street, which views newspapers as being as obsolete as a dumpster full of IBM Selectrics. Last month, the Tribune Co. threw in the towel and sold out to real estate magnate Sam Zell. It's a complex deal and far more modest than the king's ransom Murdoch is offering.

Public companies are valued on the basis of the share price divided by earnings per share, the "price-earnings ratio." Murdoch's offer of $60 a share divided by its earnings per share equals a hair over 43. His bid (which could still go up a bit) is a loopy, sky-high sum that is a 65 percent premium over Dow's recent share price. It's obvious he wants the company bad. By comparison, Gannett, the famously "well-managed" corporate journalistic homogenizer, has a P/E of just 12.

The only reason Murdoch is in the game at all, the only reason he has a chance of forcing a hostile Bancroft family to sell the company, is that as a public company, Dow Jones' chronic struggles with profitability are public property. Every public company is perpetually on the auction block. The Bancroft family tried to stave off the inevitable with a two-tier stock structure, but as they are learning, that cannot keep out a determined suitor. And with numbers like this, they may not want to.

It all comes down to values -- not journalistic values, God forbid, but shareholder value. Corporate boards are supposed to worship at the altar. If a Murdoch or a Saudi prince or a hedge fund wants to buy a company, the highest bidder wins -- unless there is a "shareholder value" excuse for him or her being passed over. And what the new owners do with a company afterward is nobody's business but theirs. Remember that newspapers don't need to exist from an investor standpoint. Remember too that this position may not seem all that terrible if it is your pension fund or 401K that is invested in a media stock.

My Dow Jones journo friend recognizes the inevitable: Newspapers, he says, are in a "contracting industry, and in a contracting industry you want a rat bastard who will restructure the costs." That is likely to mean integrating the company's far-flung operations with the rest of the News Corp. empire. Or it could mean "restructuring" in the traditional Rust Belt slash-and-burn sense of the word.

Already we're getting hints of things to come from the Murdoch camp -- such as his recent interview with the New York Times in which he expressed impatience with "long" articles in the Journal. What this means is that one of the last habitats of the Tyrannosaurus rex called "long-form journalism" is about to be covered with asphalt. Another concern is that the Journal's conservative editorial page might spill over into the news columns, as many have feared. Murdoch's comment some weeks ago that the CEO-friendly CNBC cable channel was actually hostile to business, unlike his planned Fox business channel, could be a harbinger of things to come.

If indeed Dow Jones descends into purgatory, don't blame Murdoch. What you will be seeing is shareholder value in action, and you can bet that its bounties will continue to flow even if Dow Jones eludes his grasp. Newspapers will continue to linger on as wretched parodies of their former selves, their articles shortened, their skepticism toward business curtailed and their "unnecessary" areas of coverage terminated.

The only solution is to get rid of the shareholders. Newspaper owners need to buy back their shares -- not to sell them to the local skyscraper tycoon, but to put them in trusts such as Bodenwein's, or the Poynter Institute, which keeps the St. Petersburg Times independent, or the Harper's Magazine Foundation, set up by members of the MacArthur family, which rescued the magazine from death in 1980.

There is, in other words, no solution, and what I have just described has approximately zero chance of happening. Nor is there much interest among today's moguls in rescuing the newspaper industry, not as a money machine but as a public trust. George Soros is focused largely overseas, and his hedge fund pals are more interested in being seen at the Robin Hood Foundation gala with Gwyneth Paltrow than in saving a dying industry that might have some public value.

Today's captains of industry have proved clueless, or worse, when blundering into journalism. Last year, the billionaire owner of the Dallas Mavericks, Mark Cuban, set up a Web site called "Sharesleuth" devoted to investigative reporting of crummy small companies. At first the move seemed terrific -- a supposedly public-spirited billionaire backing a notoriously unprofitable form of journalism. But then it emerged that Cuban would be trading ahead of Sharesleuth's stock picks, turning a potential boon for investors into a legal insider-trading vehicle. When critics finished retching, Cuban observed: "Our obligation is not to the reader, it is to the trading activities of our owners." In that single, breathtakingly arrogant sentence, Cuban neatly summed up the credo that is likely to put Rupert Murdoch in charge of the world's leading business and financial newspaper.

The only sliver of hope for Dow Jones would be a stiff-necked, principled stance by the Bancroft family. On Monday, two major shareholders, James H. Ottaway Jr. and his son Jay, put out tough statements ferociously opposing the merger. "As a citizen," said Jay, "I would be afraid to live in a world where news is solely entertainment, and there is an agenda behind every story I read, watch or hear. There is plenty of evidence that Murdoch does not treat his news services as a public trust."

If this were an old Warner Bros. newspaper movie, the Ottaways would pull off a triumph in the third act. But this is real life, and the Ottaways control just 5.2 percent of the voting shares. In a showdown between journalistic grit and cold, hard numbers, the numbers win every time.

Shares