(updated below - updated again)

Tony Blair, in The Sunday Times this weekend:

I was stopped by someone the other week who said it was not surprising there was so much terrorism in the world when we invaded their countries (meaning Afghanistan and Iraq). No wonder Muslims felt angry.When he had finished, I said to him: tell me exactly what they feel angry about. We remove two utterly brutal and dictatorial regimes; we replace them with a United Nations-supervised democratic process and the Muslims in both countries get the chance to vote, which incidentally they take in very large numbers. And the only reason it is difficult still is because other Muslims are using terrorism to try to destroy the fledgling democracy and, in doing so, are killing fellow Muslims.

What's more, British troops are risking their lives trying to prevent the killing. Why should anyone feel angry about us?

British colonial administrator Lord Frederick Lugard, writing in Conclusion: Value of British Rule, "The Dual Mandate in Tropical Africa", 1926 -- defending the merit and virtue of British domination of various African nations:

CHAPTER X. METHODS OF RULING NATIVE RACES.

THREE decades have passed since England assumed effective occupation and administration of those portions of the interior of tropical Africa for which she had accepted responsibility when the nations of Europe partitioned the continent between them. How has her task as trustee, on the one hand, for the advancement of the subject races, and on the other hand, for the development of its material resources for the benefit of mankind, been fulfilled? . . . .

The [Labour Party] would persuade the British democracy that it is better to shirk Imperial responsibility, and relegate it to international committees; that material development benefits the capitalist profiteer; and that British rule over subject races stands for spoliation and self-interest.

Guided by these advisers -- some of the more prominent of whom are apparently not of British race -- the Labour Party has not hestitated put forward its own thesis of Government of tropical dependencies under the Mandates. To these views I hope that I have already in some measure offered a reply, and I will endeavour briefly to summarise in these concluding pages. . . .

Let it be admitted at the outset that European brains, capital, and energy have not been, and never will be, expended in developing the resources of Africa from motives of pure philanthropy that Europe is in Africa for the mutual benefit of her own industrial classes, and of the native races in their progress to a higher plane; that the benefit can be made reciprocal, and that it is the aim and desire of civilised administration to fulfil this dual mandate.

By railways and roads, by reclamation of swamps and irrigation of deserts, and by a system of fair trade and competition, we have added to the prosperity and wealth of these lands, and checked famine and disease. We have put an end to the awful misery of the slave-trade and inter-tribal war, to human sacrifice and the ordeals of the witch-doctor. Where these things survive they are severely suppressed. We are endeavouring to teach the native races to conduct their own affairs with justice and humanity, and to educate them alike in letters and in industry . . . .

As Roman imperialism laid the foundations of modern civilisation, and led the wild barbarians of these islands along the path of progress, so in Africa to-day we are repaying debt, and bringing to the dark places of the earth, the abode, of barbarism and cruelty, the torch of culture and progress, while ministering to the material needs of our own civilisation. . . .

Towards the common goal each will advance by the methods most consonant with its national genius. British methods have not perhaps in all cases produced ideal results, but I am profoundly convinced that there can be no question but that British rule has promoted the happiness and welfare of the primitive races. Let those who question it examine the results impartially.

If there is unrest, and a desire for independence, as in India and Egypt, it is because we have taught the value of liberty and freedom, which for centuries these peoples had not known. Their very discontent is measure of their progress.

We hold these countries because it is the genius of our race to colonise, to trade, and to govern. The task in which England is engaged in the tropics--alike in Africa and in the East--has become Part Of her tradition, and she has ever given of her best in the cause of liberty and civilisation.

There will always be those who cry aloud that the task is being badly done, that it does not need doing, that we can get more profit by leaving others to do it, that it brings evil to subject races and breeds profiteers at home. These were not the principles which prompted our forefathers, and secured for us the place we hold in the world to-day in trust for those who shall come after us.

Leave aside for the moment the inflammatory question of whether it is valid to compare our invasion and four-year-and-counting occupation of Iraq and previous policies of British colonialism. There is simply no denying the glaring and substantive similarity between the "justification" for that occupation offered by Blair (and Bush and others), and the rationale justifying British colonial domination of Africa from Lord Lugard, excerpted at length here.

But at least Lord Lugard, though arguing how great colonialization was for the "native races," did not expect their gratitude. Yet it never ceases to amaze how such basic truth eludes people like Blair, who argues, in essence, that Iraqis ought to be grateful for all the opportunities the invasion and occupation has brought them.

In general, human beings do not appreciate it when foreign armies invade their nation, shatter its infrastructure, drop bombs throughout the country, kill tens of thousands of civilians, unleash anarchy and chaos, and then proceed to occupy the country with a force of 150,000 foreign soldiers. And that is true even if a genuine monster like Saddam Hussein is removed from power and killed in the process.

No matter how well-intentioned the invaders might think they are -- indeed, no matter how well-intentioned the invaders actually might be -- that behavior is going to engender anger and resentment among the invaded populace, not to mention the rest of the world, and that resentment is going to increase as the brutality and duration (and ineptitude) of the occupation increases.

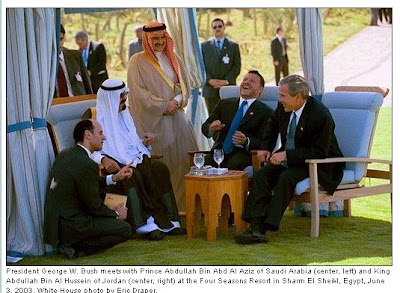

And all of that is to say nothing of the extremely precarious notion that Muslims perceive that the aim of the invasion is to bequeath to the Muslim world what George Bush calls "the Almighty God's gift to every man, woman and child": freedom and democracy. Does Blair think that people in the Muslim world don't see or understand the meaning of images such as this:

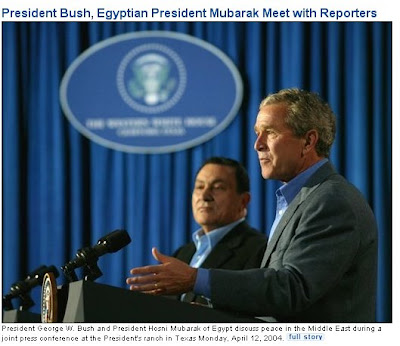

Or this:

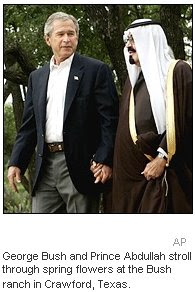

Or this:

Our closest Middle Eastern allies are some of the most repressive tyrants on the planet, while we direct some of our most intense hostility to governments far more democratic. And we demonstrate infinitely less interest in regions around the world which lack resources we want and need and/or lack countries which are of great importance to key domestic political groups. In light of these facts, how receptive are Muslims going to be to the claim that we are the bearers of "God's gift" to the Muslim world?

It is one thing to argue that we invaded Iraq in order to strengthen U.S. security. But the idea that people are going to be grateful when we invade various countries and subdue resistance with extreme violence and brutality is dangerously absurd. Echoes of the same mindset are evident now as various warmongers insinuate that the Iranian population is eagerly awaiting our "liberating" campaign of bombing and regime change.

The fact that Tony Blair -- after four years in Iraq of extreme violence, chaos, disruption, brutality, death squads, Abu Ghraib, and a total breakdown of the most basic societal functions and norms -- can ask: "Why should anyone feel angry about us?," is a potent indication of just how self-absorbed, out-of-touch, and detached from reality the prime authors of this war have been.

UPDATE: This might be one answer to Blair's question:

The poll -- the third in Iraq since early 2004 by ABC News and media partners -- draws a stark portrait of an increasingly pessimistic population under great emotional stress.About three-fourths of Iraqis report feelings of anger, depression and difficulty concentrating.

More than half of Iraqis have curtailed activities like going out of their homes, going to markets or other crowded places and traveling through police checkpoints.

Only 18 percent of Iraqis have confidence in U.S. and coalition troops, and 86 percent are concerned that someone in their household will be a victim of violence.

Slightly more than half of Iraqis -- 51 percent -- now say that violence against U.S. forces is acceptable -- up from 17 percent who felt that way in early 2004. More than nine in 10 Sunni Arabs in Iraq now feel this way. . . .

For the first time since 2003, fewer than half in the country, 42 percent, said that life in Iraq now is better than it was under Saddam Hussein, the late dictator accused of murdering tens of thousands during a brutal regime.

Conducting the face-to-face poll was a difficult ordeal in such a violent country. More than 100 Iraqi interviewers conducted the poll and some reported seeing bombings, beatings and even a mass kidnapping. Several teams of interviewers were detained by police -- but every interviewer made it home safely.

"Why should anyone feel angry about us?"

UPDATE II: This also helps to explain some of the "anger" that has Blair so bewildered:

New U.S. Embassy in Iraq cloaked in mysteryThe fortress-like compound rising beside the Tigris River here will be the largest of its kind in the world, the size of Vatican City, with the population of a small town, its own defense force, self-contained power and water, and a precarious perch at the heart of Iraq's turbulent future.

The new U.S. Embassy also seems as cloaked in secrecy as the ministate in Rome.

The embassy complex -- 21 buildings on 104 acres, according to a U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee report -- is taking shape on riverside parkland in the fortified "Green Zone," just east of al-Samoud, a former palace of Saddam Hussein's, and across the road from the building where the ex-dictator is now on trial.

The 5,500 Americans and Iraqis working at the embassy, almost half listed as security, are far more numerous than at any other U.S. mission worldwide. They rarely venture out into the "Red Zone," that is, violence-torn Iraq.

This huge American contingent at the center of power has drawn criticism.

"The presence of a massive U.S. embassy -- by far the largest in the world -- co-located in the Green Zone with the Iraqi government is seen by Iraqis as an indication of who actually exercises power in their country," the International Crisis Group, a European-based research group, said in one of its periodic reports on Iraq.

That we are constructing a permanent fortress in Baghdad and calling it an "embassy" is not fooling anyone, as this quite typical report from Al Jazeera.com, broadcast to the Muslim world, demonstrates:

Since the fall of Baghdad in 2003, about 1,000 U.S. diplomatic and military staff have been using one of Saddam Hussein's former palaces as a make-shift embassy, a move that raised concerns that the Americans merely replaced Saddam's authoritarian rule with their own. . . .The compound will cost $592m and will cover 104 acres of land, about the size of the Vatican, making it the biggest and most expensive U.S. embassy on earth.

But many analysts warn that such a move further raises Iraqi fears that the U.S. is there to stay. Toby Dodge, an expert on Iraq at Queen Mary, University of London, has just come back from a month spent in Iraq, largely in the Green Zone. He believes the Americans will not leave Iraq until the end of the next presidency at the earliest, and so he warns that the new embassy will serve its purpose for several years to come.

Perhaps Iraqis are angry because they disbelieve America's claim that its occupation is temporary, and perhaps one reason they disbelieve that claim is because of actions such as this. Or, as Avedon Carol put it today: "if you don't want insurgents to fight you tooth and nail, it would be good to show signs that you really want to get out, rather than building permanent bases in their country."

Shares