Having now carefully reviewed the Al-Marri decision (.pdf), as well as ample commentary from those defending and criticizing the opinion, there are several points worth making. But the overarching point is how extraordinary it is -- specifically, how extraordinarily disturbing it is -- that we are even debating these issues at all.

Although its ultimate resolution is complicated, the question raised by Al-Marri is a clear and simple one: Does the President have the power -- and/or should he have it -- to arrest individuals on U.S. soil and keep them imprisoned for years and years, indefinitely, without charging them with a crime, allowing them access to lawyers or the outside world, and/or providing a meaningful opportunity to contest the validity of the charges?

How can that question not answer itself? Who would possibly believe that an American President has such powers, and more to the point, what kind of a person would want a President to have such powers? That is one of a handful of powers which this country was founded to prevent.

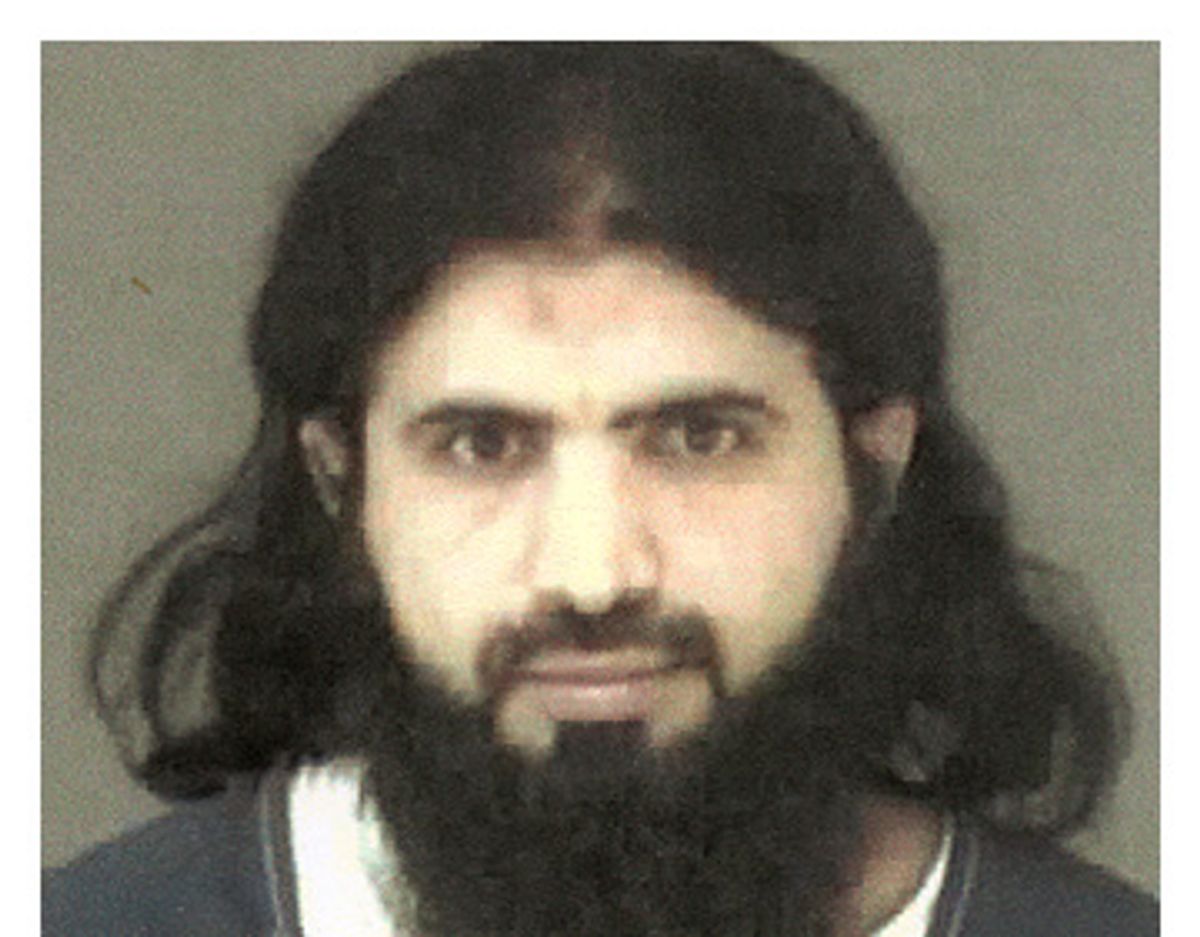

Al-Marri was in the U.S. legally, studying at Bradley University, living with his wife and 5 children, and sitting at home in Peoria, Illinois when he was detained and then ultimately charged, in a court of law, with committing various crimes. He was set to have a trial in July 2003 when the President suddenly and unilaterally decreed him to be an "enemy combatant," ordered him put into military custody, had his trial cancelled, and then proceeded to imprison him for the next four years -- including many months where he was denied any contact at all with the outside world, including lawyers -- all without charging him with any crime.

Does that even sound remotely like the United States? If the President has the power to do that to al-Marri -- to arrest him from his home inside the U.S. and keep him locked up forever without due process -- then, by definition, the President can detain anyone in exactly the same way. And all of the high-minded and oh-so-civil lawyerly rhetoric in the world cannot mask the radicalism and profoundly un-American vision which proponents of such powers embrace.

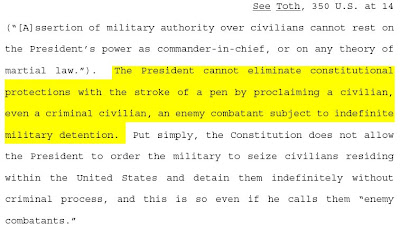

Anyone who objects to the court's decision -- and particularly anyone who seeks to vest the President with powers of indefinite, due-process-less military detention of individuals on U.S. soil -- is, by definition, advocating nothing less than the establishment of martial law inside the U.S. That is the precise point the court made, at page 72 (emphasis added):

"Absent suspension of the writ of habeas corpus or declaration of martial law, the Constitution simply does not provide the President the power to exercise military authority over civilians within the U.S."

Whether we want that is now the locus of respectable debate inside this country. Beyond that general framework, there are several specific points worth making:

(1) Those who want to vest the President with the power to detain suspected terrorists with no due process never address what checks or limits would exist on abuse of that power. Search high and low for defenders of this presidential power and see if you can find a single one who addresses this question.

Allowing the President unilaterally to declare individuals to be "enemy combatants" with no meaningful review process means, by definition, that the President's power to imprison people for life is unchallengeable and unreviewable. No hyperbole is needed to describe that as a core tyrannical power, one of the defining attributes of dictatorial rule. How does that, by itself, not end the debate over whether this is something that ought to be done?

It is just self-evident that vesting the President with this power will result in inevitable and widespread abuse of that power. That is why our system of government does not recognize such a thing as unchecked power generally or executive imprisonment specifically. Those who advocate unilateral presidential imprisonment power willfully ignore that issue and simply pretend (or blindly trust) that the power will only be used against The Terrorists -- exactly the assumption our entire system of government was constructed to reject.

(2) Despite its 77-page length opinion, the court's decision is compelled by one extremely simple and clear proposition. As Anonymous Liberal documents at length -- and as the court's opinion makes clear -- the reason that the President cannot consign al-Marri to a military prison with no trial is because doing so is against the law. Just as was true with warrantless eavesdropping and Guantanamo military commissions, the issue is just that simple, yet those who want to vest the President with these powers could not care any less about the law.

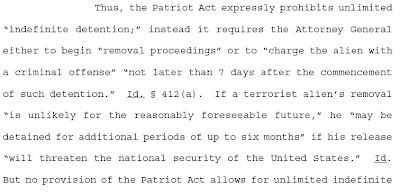

As A.L. explains, the court's decision rests on the very simple proposition that Congress, when it enacted the Patriot Act, provided a very clear legal framework for the detention of suspected terrorists inside the U.S. -- namely, it allows temporary detention but requires due process be accorded to the accused suspect. The court rested its decision on a strict statutory reading of the law:

detention.

detention.

That law is crystal clear. But yet again, the claim to power of the Bush administration and its followers is reduced to one simple proposition -- namely, that the President is greater than the law, that his powers exist outside of the laws enacted by the American people through their Congress, and that the need to fight The Terrorists means that nothing can limit the Commander-in-Chief's authority.

It is the same argument over and over -- grounded in the now-familiar Ideology of Lawlessness -- which has governed this country for the last six years: namely, the President is not a mere public servant subject to the rule of law, but is the omnipotent Commander-in-Chief who can exercise extraordinary powers such as due-process-less imprisonment even on U.S. soil without any legal authorization, and more amazing still, even in the face of clear statutes prohibiting exactly those powers. The desired power here is not only tyrannical, but completely lawless as well.

(3) As usual, those who seek to vest the President with such tyrannical power rely almost exclusively on scare tactics -- not only that the Terrorists are a grave and mortal threat, but specifically, that if we force the President to prove that individuals are actually guilty before punishing them, then all sorts of horrible things will occur.

As due-process-hating former prosecutor Andy McCarthy warns, allowing trials would mean that suspects "receive lavish discovery that could be extremely helpful to the people trying to kill us." The anti-due-process National Review identically editorializes that a terrorist suspect would "be entitled to -- and able to share with his confederates -- the fruits of discovery from U.S. intelligence files detailing the enemy's capabilities and plans."

When has that ever happened? We have tried scores of terrorist suspects now in civilian courts. Other countries, including England, have done the same. Is there a single instance where our doing so was "extremely helpful to the people trying to kill us"? And, as always, terrorist-obsessed fear-mongers focus on one side of the risk ledger. What of the risks of vesting in the President the power to imprison people inside of the U.S. indefinitely? That risk is one they studiously ignore.

Yes, it is true that due process limits what the government can do and risks allowing those who want to harm others to go free. The Founders weighed exactly those risks and concluded that it was preferable to impose those limits anyway, because effective governments can safeguard against risks within the rule of law. As big, bad and scary as the Terrorists are, it is hardly worth fundamentally revising the core calculus which has defined our country for the last 220 years. And rational people do not believe that we are incapable of safeguarding against The Terrorists without vesting tyrannical powers in our leader.

(4) Most of the criticism of this decision is based upon the claim that it rests on an artificial and meaningless distinction between (a) those who take up arms against the U.S. on a foreign battlefield (such as Hamdi and Padilla allegedly did) and (b) those who are merely alleged to be plotting within the U.S. (as al-Marri allegedly did). But that distinction is critical, not artificial, at least for those who believe in the rule of law.

The most dangerous proposition advanced by the Yoo-ian Authoritarians is that the "battlefield" in the "war on terror" extends to every square inch of the planet, including the U.S., and that "enemy combatants" are to be found everywhere and among every group -- including U.S. citizens on U.S. soil. The implication of that premise is as obvious as it is jarring -- it means that the powers that a President can exercise in war on a foreign battlefield, against foreign soldiers, would apply just the same inside the U.S., as applied against U.S. citizens or anyone else.

It would mean, in essence, that we have military rule -- with the President as Commander-in-Chief not only over the armed forces, as the Constitution confines that power, but over everyone and everything. As the court put it:  Those who are objecting to this ruling, who believe that the President has the powers claimed here, are -- by definition -- objecting to that proposition. That is how radical they are, no matter how lofty and legalistic is the language they use to express it.

Those who are objecting to this ruling, who believe that the President has the powers claimed here, are -- by definition -- objecting to that proposition. That is how radical they are, no matter how lofty and legalistic is the language they use to express it.

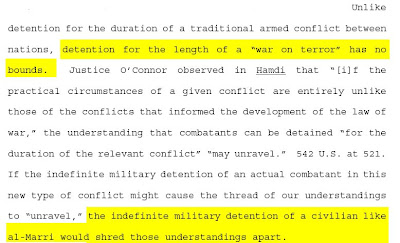

(5) There is an additional point which proponents of presidential omnipotence avoid just as steadfastly as they ignore the inevitability of abuse: namely, that this "war" is unlike all others we have fought previously because, by its very terms and by all accounts, it is one that will not be over for decades, which means the "war powers" they seek to vest in the President will change this country permanently. Again, the court described this argument aptly:

Anyone who believes that the President should have the power to order individuals inside the U.S. imprisoned forever with no charges and no process is someone who, by definition, simply does not believe in the political system of the United States.

Anyone who believes that the President should have the power to order individuals inside the U.S. imprisoned forever with no charges and no process is someone who, by definition, simply does not believe in the political system of the United States.

(6) Finally, the fact that al-Marri is "merely" a legal resident of the U.S. rather than a U.S. citizen should not obscure the fact that the reasoning of the administration and its followers in this case would apply equally to American citizens. Indeed, it is vital to emphasize that the court in this case was constrained by a prior Fourth Circuit ruling which was binding on this court that upheld the due-process-less detention of American citizen Jose Padilla, a decision which was set to be reviewed by the Supreme Court when the Bush administration finally transferred Padilla to a civilian court and charged him with a crime in order to render Padilla's case "moot."

Thus, the administration does not argue that it has the power to imprison al-Marri in a military prison forever, with no charges, because he is merely a legal resident, rather than an American citizen.

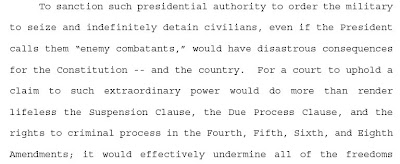

Instead, it argues -- and a prior Fourth Circuit court has concluded -- that it has the power to so detain anyone, U.S. citizens included, whom the President deems to be an "enemy combatant." Those who believe the President has and should have this power with regard to al-Marri have no reasonable means to confine that power to non-citizens (and, indeed, the administration argued and the Supreme Court in Hamdi accepted the premise that the administration can detain U.S. citizens captured on a foreign battlefield as "enemy combatants"). Their tyrannical vision -- whereby the Leader can order people imprisoned forever with no trial -- is the very one which the Founders of this country sought first and foremost to avoid. The court undescored how threatening these theories are:

Freedoms are virtually always lost incrementally. I know we are supposed to debate these matters soberly and with civility, but it is difficult to treat advocates of tyranny as anything other than dangerous extremists. The very fact that such individuals can and are openly advocating that we vest the President with the power to imprison people inside the U.S. with no charges by itself ought to be causing far more alarm than it is. This 2-1 decision may very well be reversed on appeal and was likely the by-product of a fortuitously assigned panel than anything else. If the possibility of arbitrary and indefinite executive imprisonment does not constitute a true constitutional crisis, then it is hard to imagine what would.

Shares