Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata's graphic novel series "Death Note" (whose 12th and final volume has just been published in the U.S.) is an existential horror story about the capriciousness of death. It's also fantastically addictive summer beach reading: a rocket-paced, cheerfully convoluted thriller about a psychotic, nearly omnipotent teenage serial killer -- who's the good guy, more or less -- and his nemesis, the world's greatest detective, who's also a teenage boy, and spends a good chunk of the story handcuffed to him. The series is a bestseller in Japan, where it has spawned a hit two-part live-action movie adaptation and an animated series, and it has been building up a cult following in America, too. (Meanwhile, Beijing has banned the "Death Note" books as "illegal terrifying publications.")

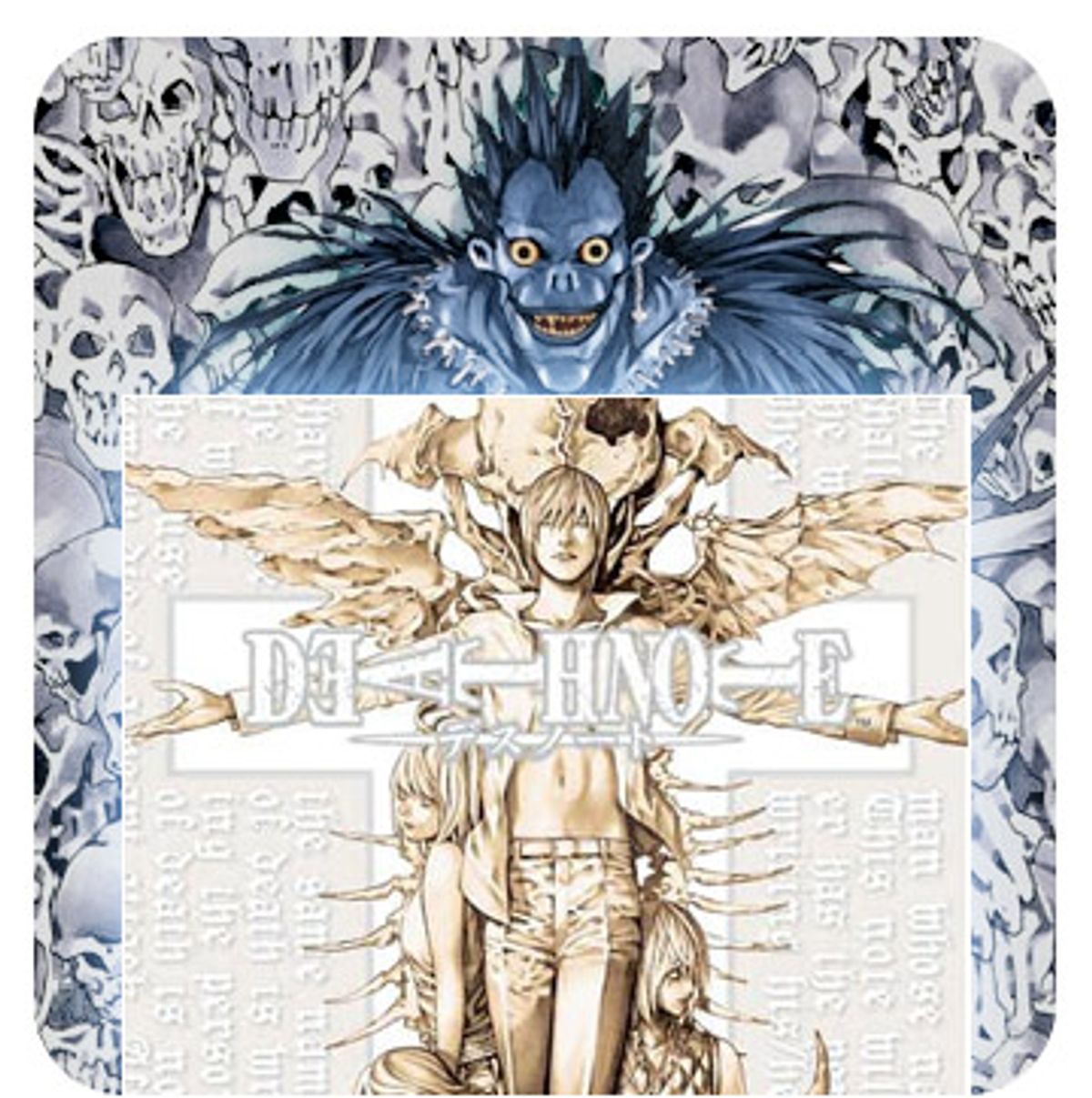

The setup is that a death god (or "Shinigami") by the name of Ryuk accidentally-on-purpose drops his notebook into the human world. Write anyone's name in the book, and that person will suffer a fatal heart attack 40 seconds later -- unless you accompany the name with an indication of exactly how and when the person will die. Ryuk's notebook is found by Light Yagami, a brilliant, aimless college-bound son of a cop, who decides he's going to use the power of life and death to make a better world. Wackiness ensues.

At first, Light kills horrendous criminals who've escaped justice. Then he starts killing criminals who haven't escaped the justice system -- and the media starts referring to the mysterious bad-guy assassin as "Kira" (phonetic Japanese for the English "killer"). Then he starts killing people who might be able to expose him as Kira, including an American FBI team that comes after him. Eventually, the Japanese police form a task force -- including Light's father -- to take down Kira, led by the aforementioned world's greatest detective, a mysterious figure known only as "L." (Actually, he's the world's three greatest detectives ... and that's just for starters. L proved popular enough that there's a separate movie about him currently being made in Japan.)

L realizes that Light might well be Kira, and that even if he's not, he's smart enough to help with the investigation -- so Light ends up joining the team that's trying to track him down. That begins the frantic, gnarled cat-and-mouse game between L and Kira that occupies the rest of the series in one form or another. The story hints at some kind of erotic tension between the two of them (this is where the handcuffs come in), but they're mostly interested in seducing each other into a trap; they're the adversaries each has been waiting all his life for.

There's an awful lot of "if he knows that I know that he knows that I know, then that's exactly what he's expecting me to do" stuff. And then ... well, it's tough to get too specific about "Death Note" without spoiling its fun -- especially since it's built on a series of massive plot twists, each of which sends it careening off in a new direction until a final philosophical whammy slams the final volume closed. Suffice it to say that Ryuk the apple-eating death god is Kira's companion, but never really his ally. As Gloucester puts it in "King Lear": "As flies to wanton boys are we to th' gods;/ They kill us for their sport."

There's a rumor that "Death Note" was originally supposed to be only about half as long as it turned out to be, but when the original Japanese serialization proved to be wildly popular, Obata and Ohba were persuaded to extend it. That makes sense, since about halfway through the series, there's a point that seems like a natural ending. It's a fake-out, but it does signal a change (which some readers hate) in the tone of the series into a parable about mortality, immortality and the difference between physical existence and identity. Near the end, there's a series of exceptionally creepy scenes in which one character is seen playing with little wooden toys that represent the rest of the cast -- and then wearing a cardboard mask of another character's face. For the first half of "Death Note," Kira and L appear to be characters like any other, but in the second half, Ohba repeatedly makes it clear that they're roles that his characters can assume or abandon.

That's a lot of weight to carry, but very little of the heavy stuff comes through on a first reading. "Death Note" is an unbelievably suspenseful story -- one of the very few comics I've read in years in which I could barely slow down enough to pay attention to its formal craft because I was so caught up in wondering, "Omigod, what's Kira gonna do next?" Ohba and Obata's style, in fact, tries to call attention to itself as little as possible. Every image and every bit of dialogue puts all its energy into pushing the story forward. There's nothing to linger over because "Death Note" does nothing but move. Even its talkiest scenes are fraught with terror; each interaction between characters, no matter how casual, is secretly an interrogation, a 20-moves-ahead push toward a checkmate. A couple of car chases and shootouts almost seem like a distraction from the story's real business of high-caliber psyche-outs.

The core of the creeping fear in "Death Note," actually, is its moral uncertainty: Most of its characters perpetually struggle with doubts over whether they're doing right or wrong. Light is an unrepentant serial killer, a butcher on an enormous scale, but he isn't a Freddy Krueger, a monster who represents pure evil, or a Patrick Bateman, a demonic symbol of his age. As coldly manipulative and egomaniacal as he is, he genuinely believes he has the moral high ground, and he sort of has a point -- Ohba suggests that Light's totalitarian world, ruled by a propagandistic TV channel and an arbitrary secret executioner, is in some ways a better, happier world than ours. And over the course of the series, we see glimpses of how the Death Note could be far worse in someone else's hands; in the books' only really weak sequence, a corporation acquires a Death Note of its own and uses it to prop up its business interests (by committee, no less).

What makes "Death Note" tick, though, is how neatly wrought its characters are -- Obata underscores their psychological interactions with telling little tics of body language. An actress named Misa Amane is drawn (and written) in Japanese comics' tradition of cute, tiny, airhead girls with big eyes, but she's a lot cannier than she pretends to be, and you can watch her measuring how much quasi-innocent charm to pour on in every situation. The Shinigami's zombified midair postures and caricatures of decay make for some crisp, dark comedy. And L is a magnificent piece of character design: chunky spikes of black hair, deer-in-headlights expression, always sitting with his knees in front of his face and snacking on candy. For all his breathtaking leaps of detective logic, he's an emotional innocent.

He's also an element in a little metatextual game: A group of major characters over the course of the series have initials in an alphabetical cluster, and the O who's never mentioned in the story itself could be Ohba himself, or an empty circle. (Ohba's name is apparently a pseudonym; his real identity is as closely guarded a secret as L's.) "Death Note" is one of those projects -- like "Harry Potter" and "Buffy" and "X-Men" -- that inspire their fans to read deeply into the story, and to imagine it extending in all directions. There are already thousands of "Death Note" fan-fiction stories on the Web, as well as mountains of fan-made art (and more than a few fan-made porn comics). Ohba and Obata drop dozens of hints about their characters' motivations and history that they never fully explain; their readers have been more than happy to pick up the clues and run with them.

Part of the fun of "Death Note" for American readers is also the way that Japanese culture frames and directs the plot. Given the enormous success of the movie version in Japan, and the fact that the story isn't tied terribly closely to the comics medium, I've wondered if a filmed remake set in America could work. I don't think so. For one thing, the peculiar logic of "Death Note" depends on unbreakable social rules that aren't nearly as stringent in the United States. Ohba's characters -- including the ones who are happy to murder with a stroke of a pen -- repeatedly refuse to take obvious courses of action that would violate their socialization and moral codes.

Even the fatal notebook itself is regulated by a series of arcane mystical laws: the precise amounts of time its death sentences can take, the consequences of giving up possession of it, its relationship to the Shinigami. At worst, an American version of Kira, whacking the bad guys left and right without blinking, would just be John Rambo. Ohba and Obata's story is just the opposite: It's built around the ever-tightening knots of moral ambiguity that come with the power of judgment, and the creeping fear that free will may actually mean nothing and personal identity may be no more than a hollow mask.

Shares