0 minutes. Former “SportsCenter” host Keith Olbermann welcomes everyone to Soldier Field, home of Da’ Bears. “We have definitely not gathered for an NFL preseason game,” he says. But many in the crowd of roughly 15,000 union workers are not listening to him. They are mugging for the camera.

2 minutes. A squinty round union boss named John Sweeney comes on-screen. “We believe one of the people up here tonight will be our next president,” he says, in a voice that sounds like air being let slowly out of a balloon. Behind him, in a pit just below the lip of the stage, workers in bright green, yellow, orange and blue shirts are waving things: hats, hands shaped like peace signs, arms. Heads bob up and down like whackamole.

4 minutes. Olbermann, who now works for MSNBC, warns the candidates to pay attention to the red and yellow lights that keep time. “Ignore the lights, we turn off your air conditioning. Second offense, your air conditioning becomes heat,” he says. He does not explain how MSNBC air conditions an outdoor football stadium. It is about 90 degrees in Chicago. Two words come to mind: union labor.

8 minutes. Illinois Sen. Barack Obama is asked to name some way the nation is not prepared for something. He immediately attacks New York Sen. Hillary Clinton, who voted in 2002 to authorize the use of force in Iraq. “Look, I don’t believe that we are safer now than we were after 9/11, because we have made a series of terrible decisions in our foreign policy,” he says. “We went into Iraq, a war that we should have never authorized and should not have been waged.” No hesitation at all — a quick jab to the chin. This man has come for a fight.

11 minutes. He is not the only one. John Edwards is asked how he would convince Americans to deal with inconveniences like traffic jams caused by repairing old bridges. He swings at Clinton, who said in another debate Saturday that she would take contributions from lobbyists. “This past Saturday, I think a very stark contrast was presented to Democratic voters in this primary,” says Edwards. “We should say: ‘This game is over. The system is rigged in Washington, D.C.’ ” It’s scored as a clean uppercut. Clinton absorbs the hit without so much as a grimace.

16 minutes. For the second time in 10 minutes, Olbermann asks the crowd to stop applauding so much. “The less applause we have, the more questions we can get in,” he reasons. But Ohio Rep. Dennis Kucinich has just called himself the “workers’ candidate.” The place is going nuts.

18 minutes. Olbermann introduces a round of questions on NAFTA, the Bill Clinton-led trade pact with Mexico and Canada that all Democrats now seem to hate. “All Democrats,” by the way, includes Bill Clinton’s wife. “NAFTA and the way it’s been implemented has hurt a lot of American workers,” she says. In the business, this is called CYA.

20 minutes. After New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson promises to get rid of “union-busting attorneys” in the executive branch, Soldier Field goes crazy with cheers again. Olbermann gives up. “We’re not going to contain the applause, I’m afraid,” he says, with apparent sadness.

21 minutes. Obama gets his second round. Of course he goes after Clinton, this time by returning to the lobbyist issue. “Are we going to make certain that you have a voice in Washington and not just those who are paying the big money in Washington to have that opportunity to negotiate?” he asks. It’s a glancing blow. Hillary is still holding steady.

24 minutes. Now it’s Edwards’ turn to take a few more shots. “I want everyone to hear my voice on this,” Edwards calls out in his best riled-up-populist tone. “The one thing you can count on is you will never see a picture of me on the front of Fortune magazine saying, ‘I am the candidate that big, corporate America is betting on.'” This is a sucker punch to Clinton’s gut. She was on the cover of Fortune in June, with the headline “Business loves Hillary.” It’s not clear how much more she can take.

26 minutes. Olbermann takes pity on the former first lady and gives her a chance to respond. Clinton plays the martyr. She announces that she will absorb the blows for the good of the party. “Well, I am — I’m just — I’m just taking it all in,” she says. Then she fires back. “You know, I’ve noticed in the last few days that a lot of the other campaigns have been using my name a lot.” This is a reference to her epic lead in the polls. A new Gallup survey, released Tuesday, shows her with a 23-point lead over Obama and a 32-point lead over Edwards. Then she says, “If you want a winner who knows how to take them on, I’m your girl.”

27 minutes. The union folk love that line. Olbermann is desperate, losing control of the crowd. He tries humor. “I’m just wondering if Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln had a moderator and if he had to try to quiet the crowd down,” he jokes.

33 minutes. First commercial break. The advertisers are precisely the kind of companies that hire big-money lobbyists to buy off politicians — the oil giant ConocoPhillips, the finance behemoth Liberty Mutual, the health insurer Kaiser Permanente.

36 minutes. We’re back. Behind Olbermann all the union folk are milling about, taking pictures, waving at the camera. They don’t sit down even though the host is trying to get on with the debate.

39 minutes. Delaware Sen. Joe Biden is sick of all the Clinton bashing. So he goes after Obama for announcing last week that he would be willing to attack Pakistan if it was the only way to get al-Qaida. “If al-Qaida establishes a base in Iraq, all these people who are talking about going into Pakistan are going to have to send your kids back to Iraq,” he says. “Let’s start talking the truth to the American people.” He is swinging a bit wild. It’s not clear if he is aiming only at Obama or at everyone onstage.

40 minutes. Clinton takes a risk and appears to compliment President Bush on the current military effort in western Iraq. “If it is a possibility that al-Qaida would stay in Iraq, I think we need to stay focused on trying to keep them on the run as we currently are doing in Al Anbar province,” she says. Nobody seems to notice.

46 minutes. Connecticut Sen. Chris Dodd is feeling left out, so he unleashes a right-cross, left-jab combination on Obama, boring down on the Pakistan comments. “I think it is highly irresponsible of people who are running for the presidency and seek that office to suggest we may be willing unilaterally to invade a nation,” he says. The MSNBC producers love it, and cut to a split screen so we can see Obama take the hits. He is stoic, with absolutely no facial expression, like a stone carving.

47 minutes. Obama ducks, returns with quick jabs, right, left, right. “I find it amusing that those who helped to authorize and engineer the biggest foreign policy disaster in our generation are now criticizing me,” he says. “You obviously didn’t read my speech.” He explains that he would only attack Pakistan as a last resort to go after high-value al-Qaida targets that couldn’t be reached otherwise.

48 minutes. Olbermann tries to bring Clinton into the fight. She obliges, effectively throwing Obama against the ropes. “I think it is a very big mistake to telegraph that,” she says of bombing Pakistan. “You can think big, but remember you shouldn’t always say everything you think if you’re running for president, because it has consequences across the world.” The Chicago crowd starts booing Clinton. They won’t let her knock out their home-state senator.

49 minutes. This is getting exhausting. Dodd says that Obama is acting “dangerous.” Obama says the American people have a right to debate foreign policy and politicians should not keep their thoughts secret. Olbermann hammers the bell. The round is over. Cut to commercial.

54 minutes. We’re back. Olbermann starts talking about the victims of mine disasters, but it is hard to focus on him. Some guy in a bright green shirt, with a big gut and thinning hair, is standing up in the crowd, pointing at his chest, as if to say, “Hey! Look! I’m on TV. Yeah! I’m on TV. Look at me! Woo hoo!” No beer cups are visible in the audience, but a flask would be easy to hide.

61 minutes. There is a heartbreaking question from the audience. A man who walks with crutches talks about losing his pension and his family’s health coverage because of a disability. His chin vibrates as he fights back the tears. “Every day of my life I sit at the kitchen table across from the woman who devoted 36 years of her life to my family and I can’t afford to pay for her healthcare,” he says. “What’s wrong with America and what will you do to change it?” Nearly the whole stadium comes to its feet to cheer.

62 minutes. Edwards is clapping onstage, with his hands above his head. “Bless you, first of all, for what you’ve been through,” he says. “You’ve a perfect example of exactly what’s wrong with America, both on pension protection and on health care.” Edwards goes on, talking about how workers should be treated like CEOs, about how America needs universal healthcare, and about all the picket lines he has walked. He goes way over time, and when Olbermann tries to cut him off, Edwards snaps, “Let me finish this.” That air-conditioning thing appears to have been an empty threat.

68 minutes. Biden isn’t done fighting. He accuses Edwards of coming late to the union cause. “For 34 years, I’ve walked with you in picket lines,” he says to the crowd before turning to Edwards. “And the fact of the matter is, it’s not where you’ve been the last two years. Where were you the six years you were in the Senate? … The question is, did you walk when it cost? Did you walk when you were from a state that is not a labor state?”

71 minutes. Edwards responds, without directly addressing how much he supported unions when he served as a North Carolina senator. He points to the fact that he was on a picket line last Saturday and Sunday. “Every president of a union who is here today and their members here knows exactly where I have been,” he says.

75 minutes. Clinton is trying to answer a question about education, but someone in the crowd is shouting something at her. She powers through. Olbermann wisely tries to go to break, but that guy with the green shirt is still behind him, doing his best impression of Homer Simpson, pointing now at his belly. The whole event is careening out of control.

80 minutes. We’re back. Olbermann is speaking but all that matters is the guy in the green shirt. He’s been making the touchdown sign. Then he turns around and points to his back. Something is written there, probably a union seal, but it’s hard to see.

87 minutes. Obama punches himself in the nose. He is asked if he would honor Giants slugger Barry Bonds at the White House for beating Hank Aaron’s lifetime home run record. Obama describes the question as an unanswerable hypothetical and then talks about cynicism in sports that comes from steroid use. “Was that a no, sir, or a yes?” Olbermann asks.

88 minutes. Obama looks confused. “He hasn’t done it yet, so we will answer the question when it comes,” the Illinois senator says. There is a safe, legalistic, “right” answer to the question, the one the commissioner of baseball, Bud Selig, is already hiding behind: You say everyone in America, including Bonds, is innocent until proven guilty, and then you stand but do not applaud. Obama, instead, drops the ball.

88 minutes. Another shot of Olbermann, another shot of the man in the green T-shirt, who has totally lost it.

95 minutes. Perhaps fearful that he has been making too much sense, Kucinich starts talking crazy. He says once he wins the presidency, Republicans will be so impressed that they will cede the 2012 elections. “I’m kind of the Seabiscuit of this campaign,” he says. Whatever that means.

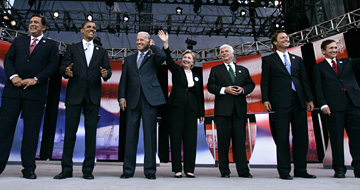

96 minutes. Finally, it’s over. Olbermann gives the stats: “One stage, seven candidates and only 96 minutes.” Then MSNBC’s Chris Matthews sums up the whole thing quite well: “It wasn’t an NFL football game, but it was pretty close.”