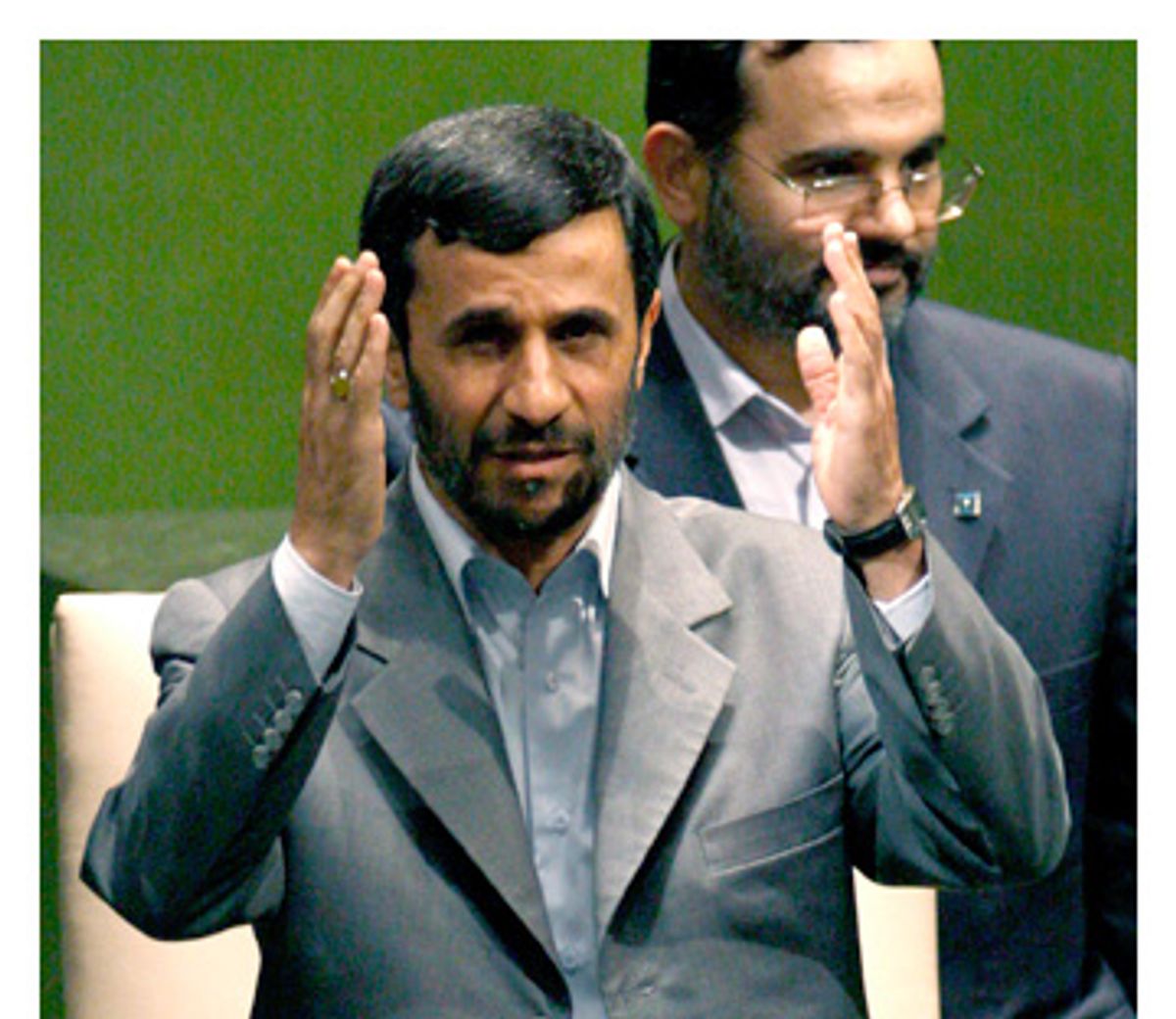

President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran wrapped up his trip to New York on Wednesday and headed south for Bolivia and Venezuela, where he will undoubtedly meet with a kinder reception than the one afforded him by Americans this week. Much has been made of the Iranian president's proposed-but-thwarted trip to ground zero, his controversial appearance at Columbia University and his theatrical speech at the U.N. But lost in all the criticisms and caricatures of Ahmadinejad as statesman -- which are often wildly off-mark in terms of gauging the president's overall authority and influence in Iran -- has been serious consideration of what his now yearly trips to attend the U.N. General Assembly signify for the Iranian political landscape and for the future of Iran's foreign policy.

I've had the opportunity to attend events with President Ahmadinejad on his three trips to the U.S. (including serving as the interpreter for his U.N. speeches for the last two), and have spent time with his aides and Iranian diplomats during the New York visits. This visit felt perhaps the most politically charged yet, and was certainly the most controversial, even for the Iranians. But amid all the theatrics, Ahmadinejad's political savvy and strategic intentions in New York should not be underestimated.

Ahmadinejad is a shrewd politician, a populist who tailors his remarks and speeches for specific audiences, and plays as good a propaganda game as anyone in the Byzantine maze of Iranian politics. Although his tactics backfire as often as they succeed, he once again managed to forcefully project himself onto the world stage with the welcome assistance of the press, and accomplish much of what he set out to do within the boundaries of his authority. The raison d'être of his visit, a declarative laying out of Iranian policy in front of the world body -- including a reiteration of Iran's nuclear ambitions -- would have to closely reflect the views of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the true center of Iranian political power. But the words uttered in Ahmadinejad's address to the U.N. would be his own, and he is not one to lose an opportunity to further his own agenda, especially in the media capital of the world.

Beyond a firm and sincere defense of his country's rights, Ahmadinejad's agenda was to inflate and burnish his image at home as well as in the Third (and particularly Muslim) World. His first stop in New York was an evening with Iranian expatriates, an event open only to Iranian media. He knew that images of Iranians inside America cheering a president who is losing popularity at home could only help bolster his image as a nationalist leader revered beyond Iran's borders. His rebuffed request to lay a wreath at ground zero conveyed to his constituents at home and abroad that whenever he tries to extend a hand of friendship, it is the Americans who rudely slap it away. His appearance at Columbia served to illustrate his graciousness in the face of open hostility by the West. And his meeting with gift-giving rabbis -- albeit from the fringe anti-Zionist Neturei Karta group from Brooklyn -- furnished images, broadcast in Iran but virtually ignored here, portraying him as something less than the bigot or anti-Semite that his accusers make him out to be. Ahmadinejad's Holocaust denial, or Holocaust questioning if one were to be generous, may be abhorrent, but the insistence in the West on inflating its (and therefore his) importance only serves to bolster his image in the Middle East. The focus there is on the second part of his infamous skepticism of the Holocaust -- "If it happened, then why do the Muslims have to pay?"

In the eyes of Muslims, his day at the U.N. served to show him as a world leader of great importance, and audiences watching throughout the Middle East undoubtedly noticed not only that the television cameras turning on him frequently as President Bush spoke, but that he politely sat and listened to Bush's speech at all. In contrast, worldwide telecasts showed the U.S. delegation rising and walking out en masse, as they customarily do whenever an Iranian president takes to the lectern. Diplomacy, which is fundamentally about reciprocity, often means that if one party snubs another, the other responds in kind -- but Ahmadinejad's tactical refusal to play by those rules and to instead show respect to the leader of the U.S., begged the question, "Who's the unreasonable man?"

Though Ahmadinejad may wish otherwise, his role in Iranian politics is in reality sharply constrained. Notwithstanding perhaps a rise in impolitic language, Iran's foreign policy is unchanged since Ahmadinejad assumed office, despite our efforts to portray him as one who has moved Iran from an accommodating and increasingly compliant and Westward-leaning society to a belligerent, defiant and threatening rogue state of the Middle East. While Ahmadinejad's speeches rely heavily on religious references -- he seems to assume that most Americans are deeply religious and will respect his piety -- very little of what he has to say, at least on issues of import, veers from what the Supreme Leader and other clerical leaders have said for years. Iran, for example, has consistently asserted that it will not be bullied into suspending or abandoning uranium enrichment, a right it has always maintained is inalienable, including under the mild-mannered, reform-minded President Khatami. Iran has also long insisted that it will never be the aggressor in any war, including against its arch-enemy Israel, a point Ahmadinejad was obliged to repeat in a press conference during this trip as well.

Ahmadinejad's dinner with members of the media and various think tanks on his last night in New York, a few hours after he delivered his address to the U.N. General Assembly, was again covered only by Iranian television cameras. It served to illustrate his reasonableness again, as he patiently answered sometimes difficult questions by tough interlocutors. Ahmadinejad, exhausted as he was by his schedule and the unfortunate timing of Ramadan, which meant his lips did not touch food or water during daylight hours, appeared satisfied and lively at the dinner. Harried Iranian diplomats accompanying him from Tehran and those based at Iran's U.N. Mission here may have had doubts about the wisdom of some of his appearances and his reception in the U.S. -- Ahmadinejad even referred to those concerns among his colleagues in comments at the dinner -- but he himself seemed to have none. The other top diplomats' voices are certainly heard in the corridors of clerical power in Tehran, and Ahmadinejad will likely face some criticism when he returns to Tehran -- but he was undoubtedly confident that his publicity was doing him, as well as his country, far more good than harm.

It is difficult to predict what the long-term implications of Ahmadinejad's circus of a visit to New York this year will be. If the U.N. Security Council is persuaded once again to impose a new round of sanctions on Iran, Ahmadinejad may be criticized back home for having been unable to move Iran's nuclear issue away from conflict by insisting on using forceful, belligerent and undiplomatic language. If, as President Bush and Congress seem to be intent on, the U.S. designates Iran's elite Revolutionary Guards as a terrorist entity (a theatrical notion of its own that would ultimately be for the propagandistic purpose of demonizing the Iranians further and keeping the Dick Cheney-backed military option close at hand), Ahmadinejad might face charges from more reform-minded clerics and politicians that his visit only pushed the Americans in making their decision. His unconventional personal views, such as declaring Iran devoid of homosexual culture (rather than his declaring Iran as literally devoid of homosexuals, as was erroneously translated in much of the U.S. media), will be seen to have contributed to Americans' notions of an irredeemable regime.

On the other hand, if Iran succeeds in delaying further action against it at the U.N., if it suffers no further uni- or multilateral sanctions that have hurt the economy -- an area where Ahmadinejad is most vulnerable -- and if the talk of war diminishes, he may well be credited for his provocative approach to foreign policy.

The Ayatollahs of Iran are never comfortable with too much attention -- and Ahmadinejad brings plenty of unwanted attention -- and they are very wary of an Iranian president establishing a cult of personality. (Khatami suffered this fear of the leading mullahs, so much so that he banned photographs of himself in government offices.) At times Ahmadinejad appears to be pushing the boundaries in cultivating his own image, especially with his grand displays in New York. But in the end the mullahs are most concerned with the endurance of the Islamic Republic and its system of government. They crave a measure of economic stability and a strong sense of strategic security -- and Ahmadinejad's fortunes will continue to rise or fall based very much on the degree to which he is seen as serving those goals.

Shares