Whether it's an old-fashioned Indian summer or a newfangled Al Gore-fueled catastrophe, the Eastern seaboard is enjoying a glorious autumnal heat wave, just as maple leaves begin to drift into backyards and prestige films begin to drift into theaters. Even in 85-degree weather, nothing signals fall like the New York Film Festival, a semi-official marshaling of the season's "important" cinema events. This year's festival opens Sept. 28 with the premiere of Wes Anderson's new movie, "The Darjeeling Limited" (look for Stephanie Zacharek's review tomorrow), and will end Oct. 14 with Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud's animated "Persepolis."

I've grumped sporadically over the years about the NYFF's slightly snooty, Manhattan-centric tone of cultural superiority, so it's time to confess to some warm and fuzzy feelings toward the grande dame of American film festivals (this year is its 45th). For one thing, as festival programmer Richard Peña observed in a recent interview with S.T. VanAirsdale of the Reeler, the NYFF is actively and aggressively curated. "The public really feels that this is a festival that is carefully selected," Peña said. "They might disagree violently with our selections, but they feel like somebody has selected these films -- that somebody has said, 'This film and not that film.'"

Peña is taking a none-too-subtle dig at his neighbors to the south, the programmers at the Tribeca Film Festival, who have jostled their way to some degree of global prominence (and/or notoriety) by seemingly screening any damn movie that's less than four hours long and pretty much in focus. There's a lot to be said for his approach. The NYFF is not trying to be a chaotic, grab-bag global marketplace like Berlin or Tribeca, nor is it trying to be an industry-insider trade show loaded with world premieres, like Cannes or Sundance. Unlike all those festivals, the NYFF is primarily aimed at the public -- a highly selective public composed of upper-end New York aesthetes and socialites, yes, but still the public.

It's no longer true that the NYFF can define the market for imported or independent film in any significant economic sense, but Peña's highly selective roster of titles -- almost all of which have already premiered elsewhere -- still captures a lot of media and audience attention. Some of this year's offerings, like Julian Schnabel's "The Diving Bell and the Butterfly" or Joel and Ethan Coen's "No Country for Old Men" or Noah Baumbach's "Margot at the Wedding" (starring Nicole Kidman), were almost foregone conclusions. Scheduling what the great Eric Rohmer claims will be his last movie, "The Romance of Astrée and Céladon," was also automatic. But every year, the NYFF committee comes up with some wild cards, like the post-Katrina documentary "The Axe in the Attic" or "Mr. Warmth," a film about the legendarily caustic comic Don Rickles. (That's right: Don Rickles. At the New York Film Festival.)

Even on a list of 29 features, there are some mystifying selections, like actress-director Valeria Bruni-Tedeschi's mediocre romantic comedy "Actresses," or B-movie god Abel Ferrara's incoherent "Go Go Tales," which plays like a spoof "Sopranos" episode. But I'll take the weird choices and the glitzy society parties, given that this year's festival is built around an extremely potent and diverse crop of foreign movies, of exactly the sort likely to play blink-and-you'll-miss-'em American engagements. These include Cristian Mungiu's Palme d'Or-winning "4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days," Hou Hsiao-hsien's "Flight of the Red Balloon," Carlos Reygadas' "Silent Light" and Lee Chang-dong's "Secret Sunshine," four movies likely to make my personal top 10 this year.

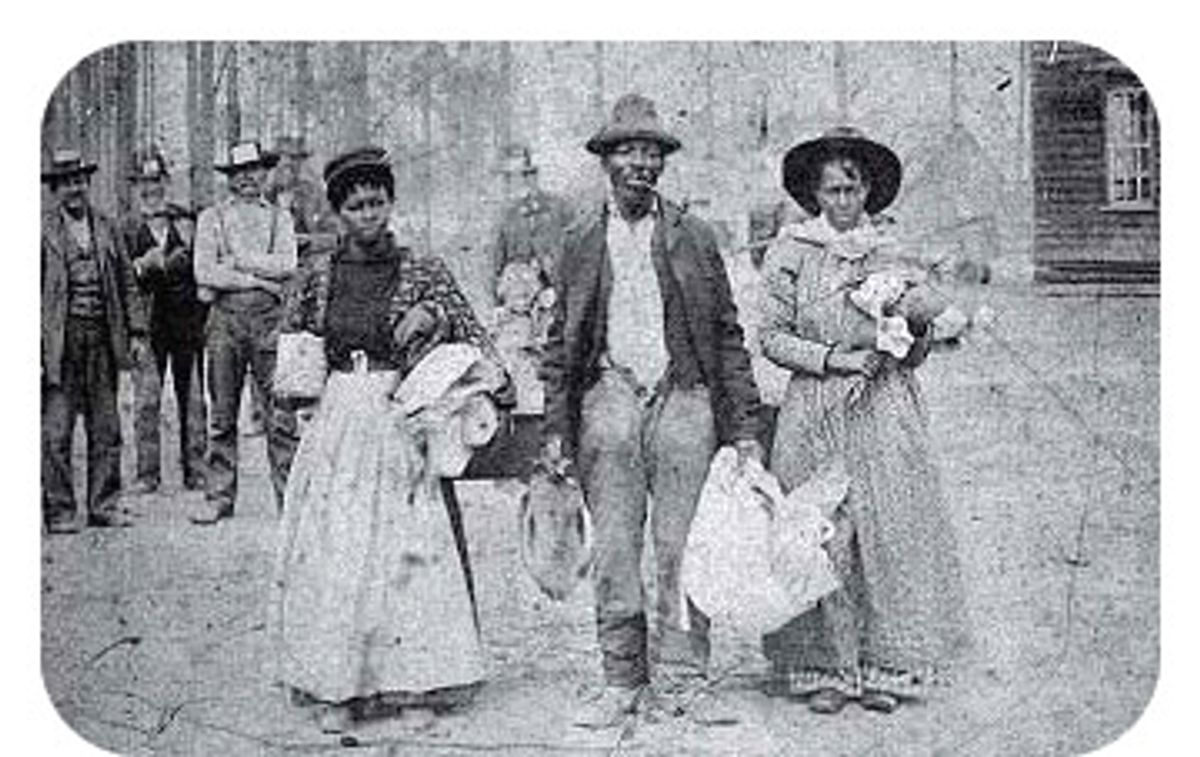

With the festival sucking up much of the media oxygen, this week's release calendar has a miscellaneous, potluck feeling. But that doesn't mean there's nothing to see. Marco Williams' extraordinary documentary "Banished" explores the buried but not-quite-forgotten history of various all-white communities in the South and Midwest (here's a hint: They weren't always that way), while Bill Haney's festival-fave documentary "The Price of Sugar" uncovers one of the Western Hemisphere's darkest secrets, the slavery-like exploitation of Haitian workers on the Dominican Republic's sugar plantations.

John Jeffcoat's "Outsourced" isn't a documentary, even though it addresses a hot-button contemporary issue. Instead, it's a highly enjoyable if lightweight romantic comedy, set in a call center outside Mumbai where Indian telephone workers sell patriotic kitsch to Middle American consumers. You can draw various conclusions from the fact that this skillful, sweet and engaging entertainment is being self-distributed, but none of them are encouraging. Let's see, what else have we got? Apparently some French dude named Truffaut made a movie about a juvenile delinquent in the late '50s. A lot of people thought it was worth seeing at the time. What does it look like now?

"Banished": American apartheid, long after the death of Jim Crow

When the aging retiree in Harrison, Ark., welcomes filmmaker Marco Williams into his home, it seems almost like the setup for a Hollywood comedy. With his mismatched outfit of high-water trousers and flannel shirt, crusty old Bob Scott seems like the irascible geezer who might just have a heart of gold; in his T-shirt, jeans and flowing dreadlocks, Williams seems every inch the big-city African-American intellectual. They sit down at Scott's table and have a pleasant conversation about life in Harrison. Scott likes living there because people are friendly, the cost of living is low and the Ozark scenery is lovely. But one factor was even more important to him and his fellow retirees, he says: "No blacks."

It is not just historical accident that Boone County, which includes Harrison, has only 40 or so African-Americans among its 34,000 residents. Nor that Forsyth County, Ga., Washington County, Ind., Pierce City, Mo., and dozens of other counties and municipalities in the Midwest and South are nearly or totally all-white today. From the end of the Civil War through the 1920s, many rural communities systematically purged their black residents, driving them out with implicit or explicit threats of violence. Sometimes these blacks were allowed to sell their land, albeit under duress and at discount prices. Often they were simply driven off, forced to abandon homes and land and flee for their lives.

Hardly anyone now living witnessed these events, but as Williams' film forcefully demonstrates, the wounds have nowhere near healed. Descendants of displaced African-Americans have passed the stories down as formative family legend, and while whites are far more eager to bury the past, many remain uncomfortably aware that something unsavory lingers at the farthest edges of community memory.

Williams focuses on three areas with distinct and disparate histories: Forsyth County today is a bedroom community on the outer suburban fringe of Atlanta, anxious to present itself as part of the tolerant New South, unshackled from the past. Yet Forsyth was the site of one of the most extensive ethnic cleansing campaigns anywhere in the country; as recently as 1987, a multiracial Martin Luther King Day march was viciously attacked by an angry white mob. Meanwhile, the descendants of black landowners driven out in 1912 have begun to seek restitution or reparations for land that was apparently stolen from them, a movement vigorously resisted by white legal and political authorities.

In Pierce City, Williams follows the painful quest of James and Charles Brown, two St. Louis brothers who discover that their great-grandparents were driven out of town in 1901, to find and remove ancestral remains from the local graveyard. Awkwardly and uncertainly, Pierce City's coroner and former mayor begin to help the Browns, and to approach their own sense of communal responsibility. But when the Browns demand that Pierce City pay for the exhumation and relocation, the tentative sense of brotherhood falls away. Why should we offer reparations, these well-meaning white citizens demand, for something we didn't do?

Back in Bob Scott's Arkansas town, the racism is more overt than in other communities. Williams has a surprisingly polite conversation with Thom Robb, head of the local Ku Klux Klan, who amiably tells him that cross burning is an ancient Scottish rite (not, of course, an act of racial hatred) but that on the whole he thinks Harrison is better off as a white town. At the same time, Harrison's white residents have done more to confront the problem than anyone in the other two areas: Local preachers have held days of prayer and atonement; volunteers helped renovate a black church in a neighboring county; a scholarship was established for African-American student-athletes from other towns.

"Banished" offers a startling tour into an unforgotten history that remains invisible to most Americans, with the erudite Williams, who is simultaneously polite and confrontational, as our host. It would be ludicrous to suggest that he doesn't take sides: Williams clearly believes that a major historical crime has been swept under the rug, and his film is loaded with moments of understated emotional power. When the black Strickland family of Atlanta find a neglected and overgrown family burial ground on white-owned land in Forsyth County, and kneel there in prayer not far from the current residents' Confederate-flag-bedecked pickup, all the legal questions and ethical quandaries fade into the background.

All the same, Williams never shies away from his film's unanswerable questions. Much as I longed for the Brown brothers and Pierce City officials to find some agreeable middle ground, both remain prisoners of history. James Brown springs his demand for reimbursement on the coroner who has befriended him, just after the latter has shipped and reinterred his great-grandfather's remains. In response, the town fathers retreat into specious and sentimental rhetoric (and refuse to answer Brown directly). Someday, perhaps, these century-old crimes will be forgotten and black people will move into places like Pierce City and Harrison, not knowing or caring about what happened there. But not yet, and not for a long time to come.

"Banished" is now playing at Film Forum in New York. Other engagements, and DVD release, will follow.

"Outsourced": Love in the fulfillment house, or the meta-outsourced indie comedy

Look, I'm not going to pretend that John Jeffcoat's romantic comedy "Outsourced" will change anybody's life, but it's an exceptionally likable film made on a shoestring -- hey, it's cheap to shoot in India! -- that couldn't find conventional distribution. If that's not a reason to root for it, what the hell is? Jeffcoat's sideways approach to a controversial social issue -- the relocation of customer-service jobs to India -- is fresh and never condescending, and the film is terrifically acted with above-average production values. Most Hollywood love stories cost 10 times as much and deliver half the juice, at best.

Actually, I wince to think what your average Hollywood director would have done with this setup: An American call-center manager is reassigned to a newly constructed building outside Mumbai, where he has to train his own replacement and ends up falling in love with -- well, with India, actually. Mind you, there is an awfully attractive Indian woman named Asha (the delightful Ayesha Dharker) involved, but acerbic Todd (Josh Hamilton) has to find out a lot about the country and its people -- and yes, about his own intelligence and conscience -- before he's ready for her.

Jeffcoat isn't afraid to make his characters both types and individuals, in the best comic tradition. Todd is likable, cynical and self-involved, while Puro (Asif Basra), the Indian manager who's going to get his job (at roughly one-eighth the salary), is hardworking, fast-talking and ambitious, with an unreadably sunny veneer. But from the beginning, we can see elements of emotional reserve and shifting intelligence in both these guys. They're always more than cultural stereotypes, and even the predictable power exchange between them -- Todd has to teach his call-center employees how to "sound American," while Puro and the other Indians have to teach him how to be a human being -- isn't as clichéd as that sounds.

Jeffcoat's depiction of the call-center world is funny, fascinating and almost anthropological; he never preaches at you on the morality, or lack thereof, of this distinct late-capitalist phenomenon. (As you may have discovered, it can be difficult to get call-center workers to admit they're not really in Chicago or Dallas.) As "Outsourced" gradually and gracefully moves Todd and the luminous Asha toward each other -- and toward the "Kama Sutra suite" of a sleazy tourist hotel -- it remains respectful of the tremendous distance between them. She, after all, has been engaged to a cousin since the age of 4, and he's on his way back to his Seattle condo as soon as the call center is down to six minutes per customer. I guess "Outsourced" is simply too bright and pleasant to become a huge hit, but it's a confident little genre film with near-classic charm.

"Outsourced" opens Sept. 28 in New York, Eugene, Ore., Portland, Ore., San Francisco, Seattle and Austin, Texas; and Oct. 5 in Los Angeles and San Jose, Calif., with more cities to follow.

Fast forward: The true "Price of Sugar" in blood, sweat and tears; "The 400 Blows" after almost 50 years

As I write this, it's still difficult to find accurate information about where and when Bill Haney's profoundly disturbing documentary "The Price of Sugar" will be opening commercially in the United States. Partly this is because the Vicini family, sugar barons of the Dominican Republic, have hired Patton Boggs, a major Washington law firm, to try to halt the film's release, or at least paint it as slanted and defamatory. Narrated by Paul Newman, Haney's film follows an Anglo-Spanish missionary priest, Christopher Hartley, as he tries to bring some justice to the slavery-like conditions under which Haitian immigrants cut sugar cane in the Vicini fields.

As Hartley remarks in the film, Americans may be dismayed to learn the true cost of the sugar they put in their morning coffee: Haitian workers are routinely imprisoned by armed guards and underpaid (or go unpaid for long periods), and those who run away or try to insist on minimal legal rights frequently disappear. While Hartley and Haney have succeeded in focusing international attention on the Dominican sugar fields, both the Vicinis and the Dominican population continue to insist that nothing is wrong. Hartley has been reassigned to Ethiopia by his church superiors, and public screenings have reportedly been interrupted by counter-demonstrators. (Scheduled to open Sept. 28 in New York, Los Angeles and other major cities.)

Every critic has their blind spots, and here's one I've never quite been able to explain to myself: I don't especially like the films of François Truffaut. I've often found them a little precious and self-congratulatory, a little too French in the most stereotypically winsome and fatalistic manner. Look, I agree that it's inexplicable, and on seeing Truffaut's prodigiously influential 1959 breakthrough, "The 400 Blows," for about the fifth time, I think I've come to terms with it.

Technically, the picture is superb, with its intimate technique, its many memorable shots -- especially that last one on the beach, when teenage runaway Antoine turns accusingly, or achingly, toward the audience -- and its simultaneously bleak and beautiful widescreen presentation of downscale street life in postwar Paris. For the first few viewings, I think I found Truffaut overly sympathetic to the delinquent hero (played so memorably by the young Jean-Pierre Léaud), and too ready to lapse into a romantic vision of a heartless, oppressive society bent on crushing the soul of the young.

Well, OK, "The 400 Blows" is about those things, but now I can see that Truffaut at least sometimes views Antoine from a dispassionate distance, about the same way he sees Antoine's maddeningly inconsistent, wounded and overworked parents. (I guess society has crushed them too.) I suspect I just didn't see this undisputed masterpiece when I was the right age for it to resound achingly in my soul or whatever. At the very least, "The 400 Blows" is a beautiful film that launched a major career and has shaped all cinematic depictions of rebellious adolescence ever since. Forget my curmudgeonly attitude and see it -- again, or for the first time -- for yourself. (Now playing in a new 35mm print at Film Forum in New York.)

Shares