Mitt Romney, in one of the most ballyhooed speeches of this presidential season, will deliver a Thursday morning address on “Faith in America” at the George Bush Presidential Library. That is the formal title for the speech anyway, but a more realistic label might be: “Can a Mormon possibly win the Iowa caucuses against a Baptist minister named Mike Huckabee?”

A minor mystery has surrounded Romney’s decision to speak at the Bush Library in College Station, Texas, rather than, say, at the Rock Rapids, Iowa, public library. John Kennedy did confront bigoted doubts about a Catholic president in his September 1960 campaign speech in Houston to Southern Baptist ministers. But College Station is 100 miles from Houston — and presumably there might be a captive audience in a church basement somewhere closer.

The Romney campaign probably had no idea, but running for president 20 years ago — almost to the day — George H.W. Bush, a born-once Episcopalian, offered one of the most curious endorsements of America’s secular tradition in political history. Asked by the Wall Street Journal what he thought about when as a young pilot he was shot down in the Pacific in 1944, Bush replied, “I thought about mother and dad and the strength I got from them — and God and faith and the separation of church and state.”

You read that right: A World War II pilot bobbing in the Pacific claimed that he thought about “the separation of church and state.” The remark was probably an early Bush malapropism and soon afterward the vice president was chided for it by Alexander Haig (another master of the English language) during a presidential debate. But it certainly did not help Bush to woo religious conservatives in Iowa, since he ended up finishing a bad third in the 1988 caucuses behind not only Bob Dole but also Pat Robertson, who was then suggesting that America should renounce its national debt with a biblically inspired Jubilee Year.

America has been wacky about religion and the Oval Office since Richard Nixon, a Quaker, asked Henry Kissinger, a non-practicing Jew, to pray during the depths of Watergate. (That incident was memorably parodied during the first season of “Saturday Night Live” when Nixon, played by Dan Aykroyd, said to John Belushi’s Kissinger, “Don’t you want to pray, you Christ-killer.”)

During a 1984 presidential debate, Ronald Reagan became the first candidate to use the terrorism excuse to explain why he did not attend religious services: “I don’t feel that I have a right to go to church, knowing that my being there could cause something of the kind that we have seen in … Beirut, for example.” Bill Clinton prayed with the Rev. Billy Graham in early 1998 on the same day that the president denied for the third time that he had any involvement with Monica Lewinsky. Graham told reporters, “I know he is sincere.”

Even with this tangled history, it is hard to recall a campaign year when electing a president has been so wrapped up in religion. Huckabee’s new TV ads promote him as a “Christian leader”; the recent CNN-YouTube debate demanded that GOP presidential contenders reveal whether they believe every word in the Bible in a literal sense; and even Democrats Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama are eager to testify to their religious faith. How far we have come in just four years from the 2004 NPR debate in Iowa in which John Kerry bravely confessed, “My experience in Vietnam … made me question [my faith] for a period of time.”

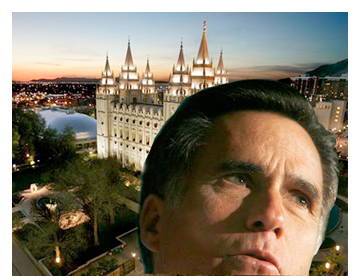

Is it a sign of societal progress that in a campaign featuring a woman, an African-American and a Hispanic, it is the straight-arrow white male Mormon who is the only major target of prejudice? All this year national polls have painted a chilling picture of the extent of religious bigotry against Mormons. A Time magazine survey in May found that 30 percent of all voters would be “less supportive” of a Mormon candidate. That figure contrasts with 9 percent who say that they would be “less supportive” of a Catholic candidate and 11 percent of a Jewish candidate.

Fifty percent of all voters in a July Newsweek poll said that America was not yet ready to elect a Mormon president. So what does America need to get ready for a Mormon president? Another 218 years of the Constitution’s barring a “religious test” for public office?

Critics of the Church of the Latter Day Saints can easily point to passages in the Book of Mormon that seem bizarre and unfathomable to non-believers. But the same can be done with the Book of Revelation or Old Testament accounts of a “wrathful” God. Religious beliefs by their very nature are not subject to the same dispassionate analysis as healthcare plans.

The only permissible constitutional grounds for raising religious questions about a would-be Mormon president is the church’s long history of prejudice against blacks. Only in 1978 were African-Americans permitted to become Mormon priests. But Romney is blameless on this score. His father, Michigan Gov. George Romney, was a liberal on racial issues during the civil-rights era and, in fact, won 30 percent of the black vote in his 1966 reelection campaign — an unprecedented figure for a Republican.

George Romney, as Theodore White described him in “The Making of the President, 1968,” was a deeply religious man who “would not talk politics or do business on a Sunday; he neither smoked nor drank; he believed, again in all sincerity, that the Constitution of the United States was a divinely inspired document.”

But Romney’s failure as a presidential candidate had nothing to do with his religious beliefs. He lost his front-runner status after confessing in mid-1967 that he had been “brainwashed” by pro-war briefings during a trip to Vietnam. (In the midst of the resulting “brainwashing” furor, Eugene McCarthy cracked, “I think in that case a light rinse would have been sufficient.”) Romney dropped out of the GOP race two weeks before the kickoff 1968 New Hampshire primary when he was down to 11 percent in the polls.

It is scary to think that in 1968 — a year when America was still partially segregated and early feminists were ridiculed as “bra burners” — the nation may have been more enlightened when it came to separating religion from politics. That is why it would be so much healthier if Mitt Romney’s fate were decided on the basis of his views (such as his refusal to call waterboarding torture) or his slippery public record (reversing field on virtually every social issue from abortion to gay rights). But there will be scant reason to cheer if Romney loses the presidential nomination because he was born Mormon instead of, say, Catholic or Jewish.