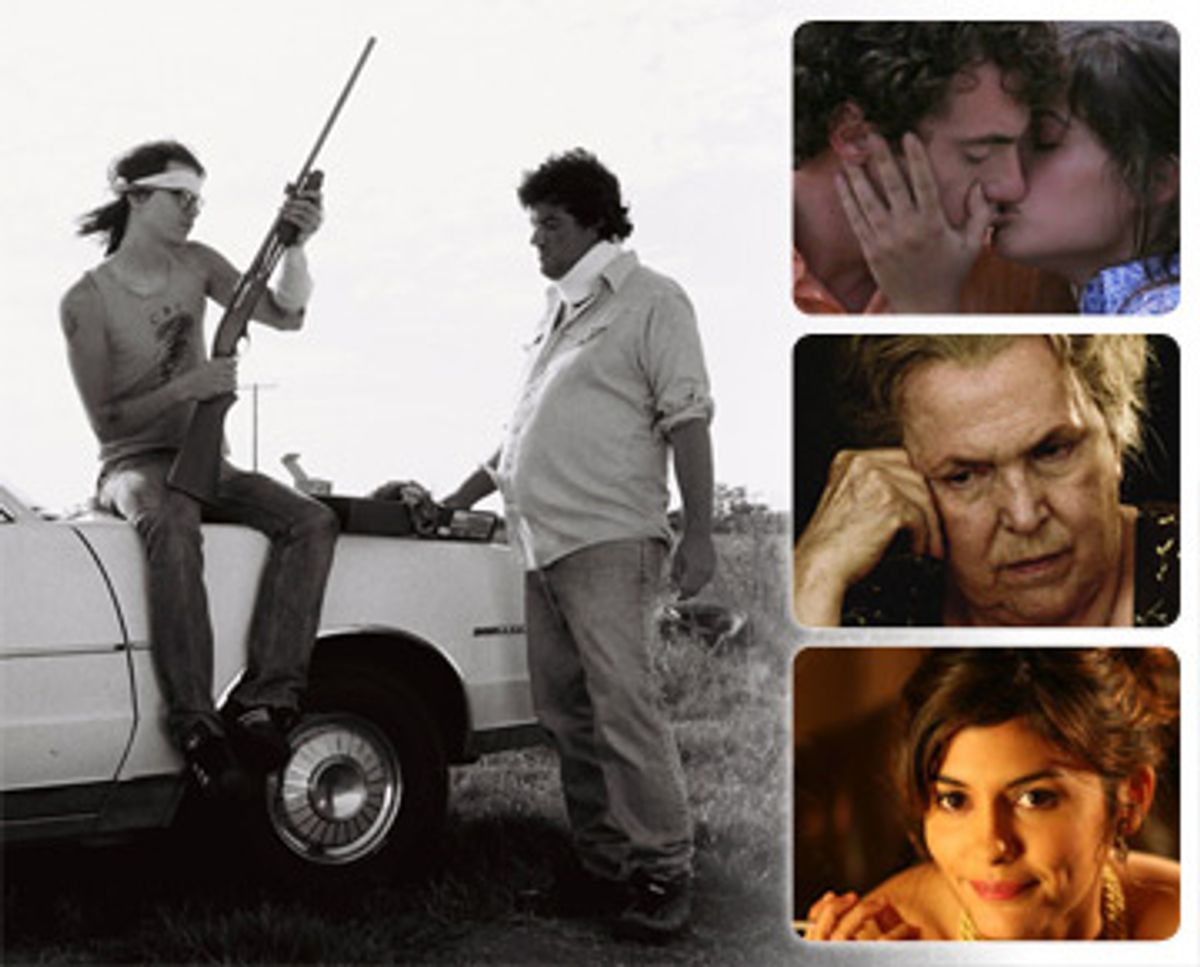

Clockwise from left: Images from "Shotgun Stories," "My Brother Is an Only Child," "Alexandra" and "Priceless."

Flowers are bustin' out all over, folks, and so is a diverse and impressive spring crop of independent cinema, including several films over the next few weeks that may be among the year's best -- but definitely not the year's most hyped. Early spring, when the earth is still cold and the morning air still fresh, and before the drums have started beating for Hollywood's Memorial Day releases, is the best time of year to catch unexpected surprises -- sometimes even good ones! -- at the movie theater. This is one of those weeks when it's no good focusing on one or two releases. It's a spring-ucopia! It's a veritable vernal basket of indies, many with thorns.

All these movies contain some violence, either emotional or physical, although the comedy might be the meanest of them and the war film the sweetest. We've got a knockout American film, with the intimacy of a short story and the violent grandeur of myth, made in the flatlands of southeastern Arkansas. We've got a haunting, strangely moving allegory about a loving Russian grandmother, made under dangerous conditions in the war zone of Chechnya. We've got a big-hearted Italian family epic of two brothers facing the social and political crises of the '60s. Oh, and we've got a guilty pleasure too -- a sweet 'n' sour, high-gloss romantic farce from the French Riviera. Plant those Johnny-jump-ups! And then let's go to the movies. (Look for more updates Friday, and over the weekend.)

"Shotgun Stories" If there's one below-the-radar American movie of the past year that has caused film buffs, on their way out of festival screenings, to call their friends and demand, "Why the hell haven't we heard more about this one?" -- that movie is "Shotgun Stories," the debut feature from 29-year-old Jeff Nichols. (It played at Berlin, Tribeca, Sydney and half a dozen other festivals last year, and has already opened theatrically in several European countries.) I honestly believe that in another era "Shotgun Stories" might have become a huge hit. It's terrifically photographed in a Terrence Malick Americana vein and well acted; it builds a powerful, never cheap atmosphere of menace without much talking.

As the title suggests, this is indeed a tale of violence and revenge, an almost Shakespearean yarn about a feud between two warring sets of half-brothers in a small Arkansas town. But that summary, while accurate, is misleading in several ways. The film's outbreaks of violence are infrequent, and Nichols never revels in them. And we're nowhere near the hackneyed, 'baccy-chawin' Hatfield-McCoy stereotypes you might expect an outsider to inflict on this story. Only a native Arkansan like Nichols could slice so near the bone of rural Southern archetype and construct a story whose characters are so sympathetic and so complex, still tied to ancient clan mentalities in a world of broken-down custom vans, endless TV sports and riverboat casinos.

Furthermore, "Shotgun Stories" is more like a languorous, ominous character study than an Okie shoot-'em-up, built as it is around the remarkable performance of Michael Shannon as Son Hayes, the sleepy-eyed, angelic-looking ringleader of three brothers without names (the others are called Boy and Kid, and yes, Nichols is flirting with caricature here) who were abandoned by their alcoholic father years ago. Son has a gambling problem -- that being his belief that he can beat the Mississippi casinos at blackjack -- and a hot temper. He definitely was not wise to attend his dad's funeral and spit on the coffin, rousing the ire of the younger half-brothers Daddy sired after he got sober and became a Christian.

But as Son sleepwalks through this dreary, trashed landscape (rendered in spectacular wide-screen images by Adam Stone), always saying less than he is thinking, Shannon somehow shows us the man's crystalline nobility and fearless loyalty. Son loves his feckless brothers, he wants to rise above his circumstances, he wants to reconcile with his estranged wife and raise his son to do better things; he genuinely doesn't want to launch a murderous dispute over a dead man in the ass-end of nowhere. Then again, how did he get all that buckshot in his back in the first place? Transcending the world we were born into is something almost no one can manage.

I'm skeptical about the recent critical attention devoted to the idea of a "new American realism," because it ain't new and because "ism" makes me want to reach for my revolver. "Shotgun Stories" would fit the profile, if anything does, but I don't want to diminish Nichols' outstanding craftsmanship here by consigning it to a pigeonhole. This movie has some Carver-esque redneck naturalism, sure, but it's also got elements of Greek myth, and Tennessee Williams gothic, and James Dean's doomed American heroism. (Now playing at the IFC Center in New York, with national release to follow.)

"Alexandra" Known mainly in the West for his 96-minute one-take historical tableau "Russian Ark," surely one of the oddest art-house hits of all time, Alexander Sokurov is widely viewed as Russia's most important living filmmaker. That fact might not help you much in trying to get a handle on his new "Alexandra," a cryptic, prickly tale about an old woman who visits her grandson and his comrades in an isolated war zone, has a series of uncertain encounters and then goes home again.

This movie, so simple on its surface and so hard to figure out, is a pretty tough point of entry to Sokurov's work, though it's not like his other narrative features ("The Sun," "Father and Son," "Mother and Son," "Moloch," etc.) are such easy assignments either. Here are the Cliffs Notes as I see them. The war in question seems to be Russia's campaign against rebels in Chechnya, and in fact "Alexandra" was shot there, under difficult and dangerous conditions. But everything about Alexandra's journey and the setting is deliberately ambiguous. The war could be almost anywhere, at almost any point in modern history -- or at least any point at which a quasi-imperial army finds itself lodged for years in hostile surroundings, and slipping into depravity and self-doubt.

To any Russian viewer, Sokurov's choice of a leading lady will be fraught with almost electrifying significance. Alexandra is played by 81-year-old Galina Vishnevskaya, probably the greatest operatic soprano in that nation's long musical history and, along with her husband, the cellist and conductor Mstislav Rostropovich, a figure long associated with artistic resistance to the Soviet regime. Although she's used to performing, Vishnevskaya isn't a film actress, and most of the other parts -- her officer grandson, his fellow soldiers, a Chechen woman who befriends Alexandra in the marketplace -- are played by nonprofessionals.

None of that would be worth bothering to know if it didn't partly account for the strange, dusty, timeless intensity of "Alexandra," or the irascible magnetism of its central character as she dispenses nuggets of dubious ethnic wisdom, complains about her aches and pains, and passes out cookies and cigarettes to the itchy, unhappy soldiers around her. (The film is shot, marvelously, by Sokurov's frequent collaborator Alexander Burov, and features a mesmerizing musical score by Andrei Sigle.) I suspect that Russian audiences -- at least those steeped in the aesthetic traditions that inform Sokurov's work -- will discern various levels of historical irony and tragedy within and beneath "Alexandra."

But I feel equally sure that the film isn't reducible to a message, about war or Russia or Chechnya or anything else, even if you grasp all Sokurov's cultural cues. Even an educated Western viewer faces real difficulties when watching Russian art films, which literally don't belong to the same conceptual universe as American-European narrative cinema and don't play by its rules. And even by Russian standards, Sokurov's films can be pretty opaque. He fully intends "Alexandra" to be a powerful and perhaps puzzling experience, a simple story full of half-buried poetic and symbolic elements. (Now playing at Film Forum in New York, with more cities to follow.)

"My Brother Is an Only Child" For some reason, even as French and Spanish movies seem to have acquired renewed cachet in the American art-house market, Italian movies have virtually disappeared. So it's worth celebrating the arrival of Daniele Luchetti's 1960s family epic "My Brother Is an Only Child," a grand entertainment that seems to pack in all the major themes of postwar European film and literature. We've got a working-class family, a misunderstood young man, communism and fascism, the Sexual Revolution, the student uprisings and their subsequent decay into paranoid revolutionary violence. All that, plus a couple of handsome leading men and a hilarious rewrite of the lyrics to Beethoven's Ninth Symphony (i.e., Schiller's "Ode to Joy") so it's about Lenin, Trotsky and Mao.

Luchetti (a leading Italian director whose only previous American release, I think, was the 1988 comedy "It's Happening Tomorrow") works here with two co-writers to shoehorn all the plot elements of Antonio Pennacchi's generational novel "The Fascio-Communist" into two hours. Despite the pitfalls of this kind of episodic storytelling -- Avuncular fascist thugs? Check! Gruff hairy commies? Check! Rock 'n' roll records? Check! Initiation by sexy older woman? Check! -- "My Brother Is an Only Child" is a vivid and exciting film, threaded together by charismatic performances from Elio Germano and Riccardo Scamarcio as working-class brothers in opposite political camps.

Germano plays Accio Benassi, a devout kid from Latina, a town built by Mussolini on the outer suburban ring of Rome. Accio goes to seminary but finds God too forgiving, and returns home to hang around with a handful of local Fascists who haven't given up on Il Duce's dream. Scamarcio, a Mediterranean dreamboat with something of the young Benicio del Toro's looks, plays Accio's older brother Manrico, who (naturally enough) becomes a Communist organizer. These two vigorous young men, virtually oozing excess testosterone, battle bitterly at home and in the streets, but their emotional and physical connection is obvious. There's nothing especially subtle about Luchetti's family melodrama, but he strikes its main notes with clarity and purpose.

Winsome Francesca (Diane Fleri), the girl whose dazzling smile comes between Accio and Manrico, never gets enough screen time to seem like a real character, but with all the male bonding and street fighting and a colorful supporting cast full of radicals, professors, chicks and goons, you'll hardly miss her. The final third of the story, once Accio has repented and joined Manrico in "the movement," gets a bit too compressed, and loses much of what's meant to be its devastating tragic impact. Such are the hazards of turning the awkward facts of familial and political history into a movie. At least this one remains a lively ride, and never becomes insipid or dishonest. (Opens March 28 at the Lincoln Plaza Cinemas in New York, with national release to follow.)

"Priceless" I guess the French just loved Jerry Lewis so much that Jerry was reincarnated -- without even being dead -- in the personage of Gad Elmaleh, the Moroccan-born comic who has gradually become a major movie star in the Francophone world. Heavy-lidded and rubber-limbed, with a fresh-faced complexion that makes him look closer to 17 than 37 (his current age), Elmaleh is paired with Audrey Tautou (she of "Amélie") in Pierre Salvadori's glossy, ruthless Riviera farce "Priceless."

I'm not going to pretend that this movie belongs in the same category with the rest of this week's list. "Priceless" has a sporadic, hit-and-miss quality about it, and I'm not sure Tautou is well cast as a heartless Côte d'Azur gold-digger who rapidly separates widowers and divorced guys from as much of their credit limit as possible. Sure, her slender, Hepburn-esque figure looks smashing in the movie's endless assortment of slinky gowns, but I'm sorry, Tautou in any role radiates sweetness more than heat. For the thwarted romance between her Irène and Elmaleh's Jean to possess any tension, she's got to be both unbelievably hot and believably bitchy.

Jean is the overworked barman at the Biarritz hotel where Irène plies her trade, and one night she takes him for an affluent fellow guest and sleeps with him, just because her older fella has passed out and she's bored. So launches a labored mistaken-identity farce, in which Jean first must conceal his servile occupation and penniless status from Irène, and then must bankrupt himself to mollify her rage. Eventually he is dragged into service as a gigolo (to a horsey rich woman played by French TV star Marie-Christine Adam), all while pining for his lost love. We're a full hour into the movie, in fact, before Irène displays signs of any motivation that isn't pure greed or hedonism. But then, there's never any mystery about this couple's final destination.

"Priceless" is better acted and a smidgen more sophisticated than your average Hollywood comedy, if also more cheaply made. As in Salvadori's last film, "Après Vous," there's an acrid, manic, almost mean-spirited quality to the comedy that seems distinctively French. (And I mean that in the best possible way.) Scenery and wardrobes are suitably glamorous and the two leads have an enjoyable, if not exactly erotic, chemistry. Elmaleh can sometimes be hilarious doing absolutely nothing, or next to it, just allowing an almost imperceptible reaction to some new bit of terrible news to spread with molasses slowness across his wistful Buster Keaton face. (Opens March 28 in New York and Los Angeles, with national rollout to follow.)

Shares