I don't know which stretch of highway was sadder: our family's drive to drop off my husband, Scott, an active-duty U.S. Navy pilot, to begin his seven-month deployment on an aircraft carrier or the drive back home without him. I sobbed quietly at the wheel, trying not to upset my two children, strapped in their car seats behind me, as we wound our way home on the gently curving roads of our rural county.

Glancing into the rearview mirror, I saw exactly what I expected. Four-year-old Ethan looked sullen and confused; he had been clingy and anxious during the big goodbye. Two-year-old Esther was too young to understand. She sang along with her "Sesame Street" CD, confident that I could provide for her health, happiness and well-being.

I didn't feel nearly as certain.

This isn't the first time I've taken care of the kids while my husband has been away for extended periods of time, but it's our longest deployment yet. (We have been lucky -- other military families have endured multiple 12-to-19-month deployment cycles since the Iraq war began.) Our Pacific Northwest town has a significant military population, and most of the people I have met here are women whose husbands are also service members. Because of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, a relentless schedule keeps many of the squadrons away from home. So we military moms talk often about ways to help our kids cope with their dads' long absences. We trade names of psychologists. We exchange tips that may ease our kids' nightmares, regressions and depression. But what I wanted, more than any of those things, was a book.

Kids' books on deployment are becoming more prevalent as the war drags on; these stories, often self-published or from small publishing houses, try to explain to the 2-to-5-year-old set why Dad must help children overseas instead of staying home to play with them. I have always found comfort in literature, in the power of a shared experience to bring consolation during difficult times. So I prompted other military moms for authors' names. I haunted the aisles of local shops and spent hours online. I borrowed other families' deployment-related books and lent out my own. I amassed quite a children's library -- a heartbreak hotel of titles I wouldn't wish on anyone. The books I found are well-meaning, almost painfully sincere in their effort to address a child's fears and feelings. They end in joyful homecomings.

But talking to a kid about deployment is like talking to a kid about God: Every parent has his or her own approach. And I couldn't find one single children's book on deployment that I could read without cringing.

I knew exactly what I wanted: the military version of "Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day." I envisioned a story that allowed kids to acknowledge their anger or sadness at Dad's absence, even wallow in their bad mood if necessary -- all while transmitting the assurance of a better day.

But even in the most sensitive and tender children's books on deployment, I found jingoism ("Your daddy had to go to war because he said he would. A war is something that our nation believes is all good"), reflexive sloganeering ("'You are Uncle Sam's kids,' said Daddy") and a whiff of xenophobia ("Mom watched the news and she said, 'That's where Daddy is ... Iraq.' It didn't look like a very nice place.")

In others, politics intrude in a startling way. In a self-published title available on Amazon, the 11-year-old narrator says, "How can Uncle Sam be so unfair to the little people? Come on, isn't it bad enough that my dad was ordered to fight in a controversial war, just to look for bad men who carry guns and wear dresses?" The section continues, "Where is justice for the little children all over America, who have to stand by and watch their mothers and fathers go off to war?"

Partisanship aside, the allusions to Iraq, or to combat, may be reasonable for older children who watch the news. But I found it totally unacceptable for the younger ones, kids who are developmentally unable to process anything but the basics: Dad's gone, but he loves you very much, and he can't wait to come back so we are all together again. And it's OK to be mad about it.

That's why I avoided talking to Ethan and Esther about the war. As the countdown to my husband's deployment began, we described his "long trip for work." The thought of transmitting any deployment-related details to my kids paralyzed me with fear. I didn't want to be the one to shatter their innocence. I didn't want their innocence shattered, period. I stuttered out vague explanations for the pro- and antiwar rallies we drove past on Sunday mornings when Ethan asked why people were holding up signs and shouting at one another.

I just prayed he didn't hear about the war from anyone else. Though I understand the importance of telling children the truth, "Dad's in a war" is among the ugliest truths there is, and I planned to shield him from it for as long as possible.

That turned out to be a month.

Ethan's friend, a 5-year-old boy we adore, came over for a play date shortly after my husband deployed. As I made pizza in the kitchen, I watched the two boys swordfight, fit puzzles together, lounge against each other on the couch as they watched a video. The little boy got up, wandered around the room, and stopped in front of a photo of my husband in uniform.

"Is your Dad in the military?" he asked Ethan.

"He's in the Navy," Ethan said proudly. And I was proud, too -- of him, for the dignified way he responded, and of myself, for transmitting the idea that he should be pleased with his dad's service. My efforts were worth it, I thought. Those jagged explanations, awkward and unpracticed, actually worked.

"People in the Navy kill people," the little boy said.

My scalp tingled with fear.

Ethan's buddy was the child of civilian friends who, I discovered afterward, support the troops but openly discuss their antiwar feelings with their son. Every parent will choose what's best for their kids, of course. But now our two boys stood face to face, arguing about whether or not Ethan's father was a murderer.

Ethan's nightmares began that night.

So I made an appointment with a civilian social worker on base. I wanted to ask if she could recommend a way through the crisis. I wanted book titles, too -- I hadn't abandoned that dream. Ever the diligent student, I uncapped my pen as soon as I sat on her couch. I jotted down tips, ideas, resources and her thoughts on our particular situation. None of it was very satisfying.

"I'm just not sure how to explain it all to him," I finally confessed.

"Could you tell him his dad is fighting for freedom?" she suggested.

I put my pen down. Now I was truly alone.

"No," I said.

I had come in search of a road forward, but instead I found myself on a brain-rattling gravel path that dead-ended in the middle of nowhere. There were no thoughtful answers. Even a trained social worker was offering slogans as a method -- or a substitute -- for coping. Maybe there was simply no good way to maintain a child's emotional health during deployment, because sending a father off to war is an abnormal, traumatic experience that is rectified only when he returns. (Or perhaps never, for all I knew.) Maybe I hadn't been able to find any satisfying children's books on deployment because there just isn't anything reasonable to say.

When I arrived back home, I reexamined the pile of books I'd rejected months before, wishing just one held the key. I knew nothing could lessen the kids' yearning for their dad. I wasn't looking for that. I just wanted the deployment to make sense to them, in the most personal way possible.

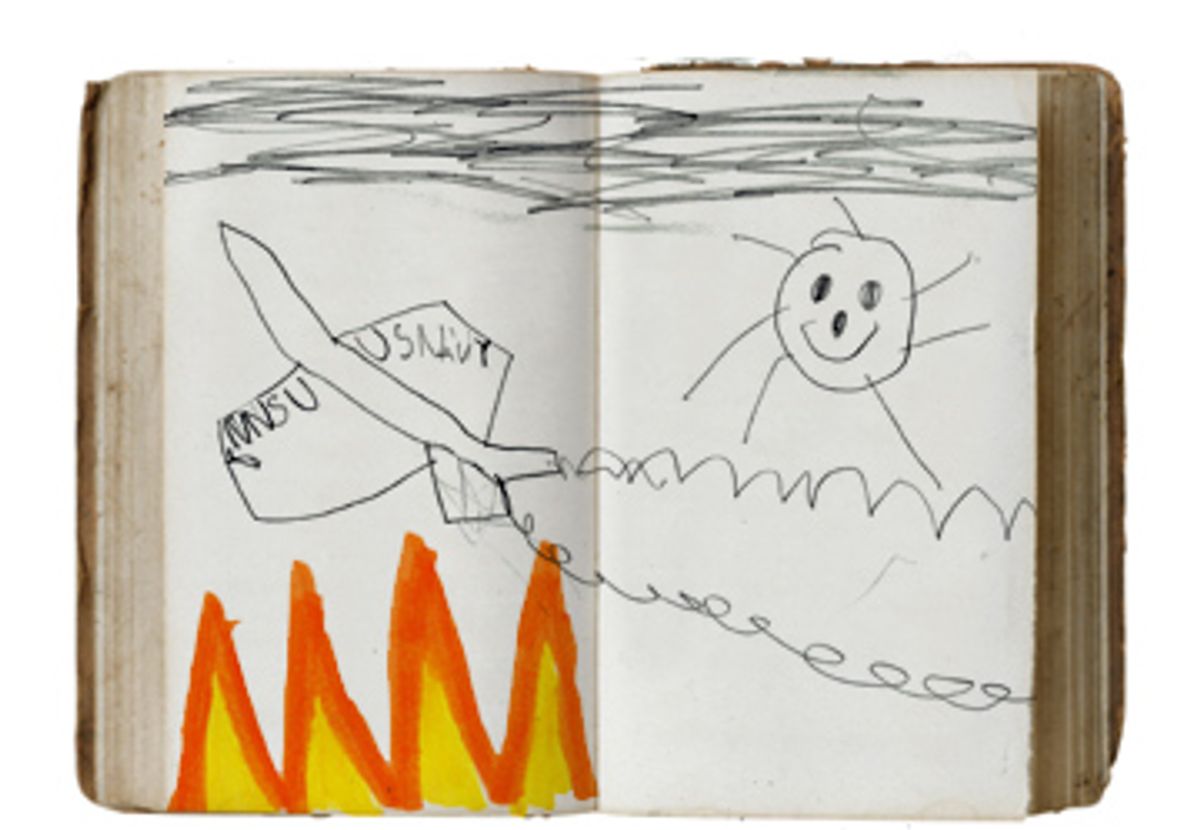

Normally, writing would have been my answer. But I write newspaper and magazine articles, not children's books. Still, at my desk one morning, I started absent-mindedly drawing pictures of Ethan and his dad on a page in my notebook. I stuck a few happy-face stickers around the edges. I felt like I was in kindergarten. Then I wrote a few captions for the drawings, but I started running out of space, and my handwriting was sloppy, so I opened up my laptop.

When I looked up next, a few hours had passed. I printed out a dozen pages, and decorated them with stickers and stamps. I glued on photos that Ethan had never seen before. I stapled a makeshift binding along the side. I called my book "The Good Day: Having Fun While Dad's Away." It held between its two thin covers everything I wanted to say to the kids about Scott's deployment. My credentials were tenuous. I was just a mom. But that qualified me as an expert in the small picture: the domestic sphere.

The next day, I asked Ethan and Esther to sit next to me on the couch. I reached for the book. Ethan was uncharacteristically withdrawn, but he oohed and aahed over the stickers. The kids turned each page together as we read. I wondered, yet again, if I was handling the separation the right way. After all, I had pored over volumes of pamphlets and fliers on getting kids through deployment. No one ever mentioned writing one's own book.

As we reached the last page, Ethan looked up at me.

"Mommy?" His eyes were shining. Were those tears?

I felt I had totally blown it. Perhaps our military family in the making, still so emotionally fragile, could not withstand any further trauma. In that moment, I second-guessed myself on everything that had taken place since the day Ethan was born. Suddenly parading before my eyes were four years of bad decisions, missed opportunities and wrong turns that would surely land us on the "Dr. Phil" show.

"Mommy?" he repeated.

"Yes, my love?"

Ethan smiled the lopsided, closed-mouth grin that reminds me of my husband. It was the first moment in weeks I'd seen a spark of his old self.

"Read it again."

Shares