To listen to a podcast of the interview, click here.

To subscribe: Click here to add Conversations to iTunes or cut and paste the URL into your podcasting software:

A few years ago, when I was moonlighting as an instructor at New York University, I led a group of incoming journalism students on a tour of the old New York Times building on West 43rd Street. When Times reporter David Carr saw me across the newsroom, he jumped up from his desk, leaving whatever fast-breaking media-business story he was working on, and spent the next 20 minutes showing the awestruck freshmen around the paper of record, narrating in his gravelly Minnesota drawl.

It wasn’t like we were bosom buddies. I’ve known Carr as a professional colleague since 1994, but we don’t socialize and I’ve never met his family. Still, to use an appropriate Middle American idiom, David Carr is a stand-up guy. If he knows you and likes you — and David knows and likes a lot of people — he’s likely to do you a solid. I don’t have to wonder whether he would try to help me if I were in dire straits, because I already know. When I lost my job as editor of SF Weekly in 1995, David called to ask if I wanted an inside-track recommendation for his old job at the Twin Cities Reader in Minnesota. Nothing personal, Gophers, but I moved to New York instead.

I dimly understood that Carr was in recovery, but that amorphous term captures lots of people I know. His battered visage and bourbon-and-ciggies voice only augmented his hard-boiled reporter persona — and as anyone who has read Carr’s media-business coverage, his post-Katrina reporting from New Orleans or his Carpetbagger blog during Oscar season is aware, he’s one of the craft’s consummate professionals. The David Carr I know is a charmer, a survivor, a party boy turned family man.

I definitely don’t know the David Carr who can’t remember being arrested for beating up a Minneapolis cab driver, can’t remember one entire stint in rehab, can’t remember going over to his best friend’s house dead drunk and pill-addled with a gun in his hand. I don’t know the guy who, by his own account, was smoking crack on the day his twin daughters were born (as was their mother), or the one who describes himself in his memoir, “The Night of the Gun,” as a fat, coke-dealing thug who beat up women.

But here’s the problem Carr confronts in “The Night of the Gun,” which is, on both a technical and a philosophical level, the most challenging memoir produced to date by the ex-cokehead mea-maxima-culpa genre: He doesn’t know that guy either. Carr’s book has two overlapping and arguably contradictory narratives, one of which follows the Dostoevski-by-way-of-Oprah model of abasement and redemption the reader expects and the other of which, let’s just say, does not.

In the first instance, Carr’s story is an inspirational, almost miraculous one: A massive fuck-up who had blown out his journalism career and virtually been abandoned as a hopeless case by friends and family, finally gets sober after his baby girls are born. He rescues them from their increasingly dysfunctional mother, gets them off welfare and raises them as a single dad. (Yes, Carr reports, unspoused fatherhood is indeed an effective chick magnet.) Along the way he survives cancer, falls in love, gets married and has a third daughter, prospers professionally and finds himself, in his 50s, with a great job, a beautiful family, a house in the suburbs. Yes, there was a fairly recent relapse — alcohol, not cocaine — but that, too, is almost a ritual element of the narrative.

When that guy, that middle-aged recovering cokehead, decided to go back and tell his own story, he brought the tools of his craft with him. Rather than relying on a faulty and poisoned memory, Carr tracked down old friends, ex-lovers, former dealers, bosses who’d fired him, disbarred attorneys, de-licensed shrinks and a rogue’s gallery of other characters. (One of Carr’s old Minnesota partners-in-crime is the comedian Tom Arnold, who appears here with no attempt at concealment.) He recorded every interview on audio and/or video, and scanned in every legal and medical document he could find. He hired two private eyes and a backup reporter to gather loose threads behind him.

This means that Carr’s book isn’t likely to have any major truthiness problems, à la James Frey’s “A Million Little Pieces,” but all that reporting has produced other, more interesting consequences too. One of them is the book’s Web site, a masterwork of commingled confession and self-promotion that includes a large trove of the documents and videos yielded by Carr’s research, along with such things as a letter from the mother of his twin daughters that is almost too painful to read.

Carr’s journey into the past leads him to his second story, a confrontation with a not-so-pleasant version of himself. He didn’t go into this project knowing that he would discover arrests he couldn’t remember, or that his ex-girlfriend Doolie would demonstrate how he used to beat her up. Or that his old friend Donald would tell him that it was David who packed a pistol during the late-night standoff that gives the book its title.

Considering that evening, Carr wonders: “Can I tell you a true story about the worst day of my life? No. To begin with, it was far from the worst day of my life. And those who were there swear it did not happen the way I recall, on that day and on so, so many others. And if I can’t tell a true story about one of the worst days of my life, what about the rest of those days, that life, this story?”

Although he’s a confident and tenacious reporter, Carr has the perspicacity to see that his methods are not likely to yield some unalloyed, unambiguous version of the truth about himself or anything else. All of us, he suggests, would likely face similar problems if we looked at our own past through the eyes of others.

The problem with “The Night of the Gun,” you could say, is that Carr wants to have his epistemological cake and eat it too. He engages difficult questions about the constructed and self-serving nature of memory and about the fungibility of that mystical entity called the self, but he also seeks to deliver the final, redemptive hug (his word), the promise of better things that the recovery fable demands. Perhaps there is no contradiction, only the fact that we want to see clear-cut moral narratives in human life where none exist. “Which … of my two selves did I make up? Carr asks himself. The only possible answer is neither. The fat thug and the stand-up guy are both real, and bear the same name. The passage that led from one to the other can be explained as a chemical or physiological or spiritual transformation, but what really matters is that it happened, not why.

David Carr met me at Salon’s office for an extended conversation about “The Night of the Gun.” We hadn’t seen each other since that day at the old Times building. As you’ll see, some tension arose between us when I suggested that his account of his relapse into alcohol abuse (circa 2002-05) might not adequately address the loss of trust some readers may feel, reasonably or not. The way I phrased the question was, in fact, chickenshit, but it’s a legitimate question anyway. (To listen to a podcast of the interview, click here.)

Video: David Carr on his memoir

David, when you decided to approach this story of your career as, should we say, a massive fuck-up …

We should say that, yeah.

You went at it with the tools of your trade, as a reporting project more than a memoir. What led you to do it that way?

A bunch of things. I had always said that I wouldn’t write this book, or a book like this, because there’s a lot of ’em. And then I decided, “Mm, maybe I will. Maybe I could write a good one.” At the time, the Smoking Gun had introduced a whole new level of transparency. That got me thinking: What do I really know about what happened to me? What would it be like to go back?

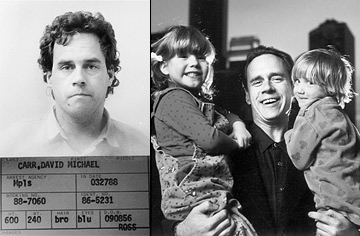

Actually, the seed got planted a long time ago when I was the editor of the Twin Cities Reader, and Rose Farley, one of the best investigative reporters in the city at that time, went to city hall for some other reason and came back with my mug shots. She plastered them all over my door, and I was the boss of the paper at that time. Everybody had a really good time with that, choosing their favorite.

How much did the decision to report your own story have to do with cases like James Frey’s memoir, which apparently should have been published as fiction?

I’m pretty much a basic, straightforward reporter, and I thought if I took the approach of just going and looking, that I would find new things, have some epiphanies. It was a short step to saying I wanted to relentlessly document everything, and that might have had something to do with the fact that memoirs were coming apart in plain view.

I want to make it clear, though. It isn’t like, oh, every word is a shiny diamond of truth. It’s like all human endeavors. It’s probably got errors in it, and errors of omission. I wanted to make it as truthful and transparent as I could. So I videotaped all the interviews, I scanned all the documents, I recorded all the audio and I had somebody else transcribe the tapes, because I think we even hear what we want to hear sometimes, and shave off a corner here or there when we’re transcribing.

You make it very clear that even this method isn’t going to get you to the unique and unvarnished truth.

I don’t want to draw a target on myself. I don’t want people saying, “Aha! Isn’t it true that you blah-blah-blah?” And my timing sucked, frankly. I went back 20 years later and the document trail had really gotten a lot thinner than I was hoping. A lot of medical records were gone, a lot of arrest records were gone. Stuff I found absolutely fascinating, I couldn’t really prove. So I hired one private investigator and then I hired another private investigator, and I learned what everybody learns, which is, if you’re doing a story it’s best to hire a journalist. So I hired this reporter named Don Jacobsen who went back behind me and found some stuff and couldn’t find some stuff. It let me write with a little bit more ease, because if that guy can’t find it and I can’t find it, it probably can’t be found.

My main criminal defense attorney had been disbarred, my mentor is in federal prison, my therapist lost his license. Let’s just say that all the encounters with me didn’t do great things for people’s careers.

You have this joke about how readers will look for the “yucky parts” so they can feel better about themselves, and you certainly supply that stuff. You write about getting high, actually smoking crack, on the day your daughters were born.

Their mother denies that. But I really and truly believe that it happened.

Well, you include a hospital report that indicates a strong probability that you guys were high when you got there.

Which is why I thought I remembered it correctly. It goes with my theme of only being able to remember what you can stand to.

And you uncovered several things you couldn’t remember. You had at least one stint in rehab you didn’t remember, and at least one arrest, maybe more.

Several. That’s correct.

You parked a car somewhere in Minneapolis and never found it again.

My brother, who gave me that car, carries a resentment about that to this day.

I mean, completely losing a car is kind of a funny story …

Unless you need one.

But smoking crack on the day your kids are born is a lot less funny. Nearly killing yourself and your kids in a head-on collision because you’ve been drinking and driving, which happened a lot more recently — that’s not funny at all. You’re walking a razor’s edge in this book between hilarious yarns about your cokehead misadventures and stuff that’s genuinely shocking.

I would say that when I was writing this I didn’t know what I was doing. I have a context for everything that occurred in my mind, and it turned out great. I have a job I like and I’m married to someone I love and my daughters are fine. But I would say this: The story changed when I went and reported it, but it sort of changed when I wrote it too, and it ended up in the hands of other people. The atavism and violence and recklessness of some of the things I had done, which seemed very distant to me and not a part of who I am, have re-imaged me in the present. I wasn’t really ready for that. I feel normal. I don’t feel like a maniac.

Your original version of the story, the classic narrative of abasement and redemption, as you put it — a story of a guy who does terrible things but mostly means well — did not completely hold up once you started reporting it out.

There’s two stories here, and I tend to focus on one of them. The whole “everything was horrible, now everything is good” story, which is a meme of culture, doesn’t turn out to be true in my life or anybody else’s either. I mean, it turned out pretty nice for me, believe me. A lot of people I went back to see were under headstones.

Early on in the book you have this devastating sort of list, with the headings “Here Is What I Deserved” and “Here Is What I Got.” Under the first heading you’ve got hepatitis, HIV, homelessness, federal prison and an early, miserable death. Instead of that, you’re married, you’ve got a great job, your kids are healthy and you seem like a well-adjusted middle-aged guy.

Unless I jump up and start choking you in the middle of this interview. Don’t say the wrong thing! You don’t know, man!

And then you ask how the first guy turned into the second guy, and admit you have no idea.

I wrote a whole book and I still don’t know. My dad said, “Well, nuns prayed for you.” You know what? I’m going with that.

A couple of things happened for me. I came from a really nice family, so when I got custody of my kids and demonstrated some resolve, they came swooping in. My mom did laundry, my brother got me a car, etc. Many people I had worked with before gave me jobs. I got a lot more breaks, being born of means, being white, being college-educated, being male.

And apart from that, I did the work. I did both the work of recovery and the work of craft. In professional terms, I don’t think anybody would accuse me of being excessively brilliant or some kind of extraordinary writer. I’m an earner and an autodidact, and if you take those obsessions that may have been arrayed over other things and apply them to journalism, they’re going to yield some blessings.

Explain why the book is called “The Night of the Gun,” because it isn’t obvious when you pick it up.

I loathe guns. I loathe people who carry them, and now I have a book called “The Night of the Gun.” There was this one night — and anybody who’s had issues with substances has stories something like this. I got fired, I drank too much, I took some pills and ended up out of my skull at my friend’s house, trying to kick the door in. As I remembered it down through the years, he finally came to the door with a handgun and said, “You have to go away.”

At the time, I forgave him almost immediately, because I was being a jerk and he probably wouldn’t have shot me. But when I went back to see him 20 years later, and he listened to the whole long story about what happened that night, and then said, “Yeah, that all happened. Except for the gun — I think you had it.”

I was like, “Oh sure, I came wobbling up to your house with a handgun.” But then, a year later, I was talking to another friend, a professor of creative writing in New Orleans who was around at the time. He had moved me once in the dead of night, and he was the one who had to go back into my house and get my gun.

And you had no clear memory of ever owning a gun?

No. I can accommodate a lot of things, and I did get into a lot of jams here and there. But no matter how drunk or crazed I was, I couldn’t see myself being the kind of person who waved a gun around.

You said earlier that there are two stories here. They’re contradictory currents in some ways. There’s the forward momentum of this story about a guy who screws up massively and then begins to put his life together. And then there’s this other story about that guy later, beginning to discover that the truth is not exactly what he thought it was. And that raises questions about whether his self, or anybody’s self, is what we think it is.

When I was writing it, up in the Adirondacks, there was something head snapping about the present tense and the past tense, looking back and moving forward. I was worried it would be bumpy and unreadable. I didn’t want to go with a straight chronology, and I wanted to put out an early template saying that everything turned out OK, because why would the reader crawl across broken glass otherwise? You know, the demographic for the book so far has been women of a certain age, and I don’t think they’re sticking around to see what happens to me. They care about those kids, and they want to find out what happens to them. The jerk that they’re stapled to, they just kind of keep an eye on him along the way.

In your first few chapters, you engage in some fairly heavy-duty philosophizing about the nature of memory, about what we know about the past. “We all remember the parts of the past that allow us to meet the future,” you write. The way we see ourselves is a tool that allows us to keep going, whether or not it bears much relationship to the truth.

It’s an ancient human impulse and a current meme of culture, to make yourself up and invent yourself. At the same time, there’s all this cheap, ubiquitous technology that’s overlaid on that. There’s almost this life-blogging going on. It’s like they say in certain recovery movements: “Damn what you say, I’ll watch what you do.”

I have no academic background in philosophy or anything, but I did do a lot of reading and tried to come up with these synthetic rails I could move the book down. Some of my friends said, “It’s been said by others and said better, so don’t go there.” I said, “But that’s really my book.” Otherwise I’m just, I went here, then I drank too much, then I shot dope in my eyeball, then I found Jesus or whatever and now everything is new again. I don’t want to write that book. So this is my added value. I do wish I’d started earlier and been more thorough with the investigation, and I wish I’d gotten help earlier on, because we might have found additional stuff. What drives the book narratively is the reveals: I thought things were this way but they were really that way.

Right. One of the most wrenching stories is when you go back to interview an ex-girlfriend, whom you call Doolie, and she remembers you clearly as an abuser. Not just verbally or psychologically but also physically.

Yes.

And you didn’t remember it that way.

No. I remembered that we had a very physical relationship in all regards, and that she had done things to me and I had done things to her. Of course, with the benefit of hindsight, 20 years later: I weighed 250 pounds. I was in complete physical control of any situation I was in. So regardless of whatever the precursor event was, I totally could have walked away, and what I chose to do was stand instead, and inflict, uh, pain. She even demonstrated how I did it.

It’s sickening. I have 20-year-old daughters, and I haven’t been in a fight in several decades. I’m not a person who’s going to hop out of his car and start screaming at people. I’ve read in some reviews about what a profound lack of self-awareness I’ve shown around that and other matters. I really can’t explain it. A lot of people drink and don’t hit people. There are a lot of ways to be a drunk or a junkie. I’ve made that speech myself. Why did I choose this way? What does it say about my character or my history?

How tough was it to to go back and meet with Doolie, and with Anna, the mother of the daughters you ended up raising? These are two women who don’t necessarily have the fondest memories of you.

[Long silence.] The thing with Doolie was like — I was incredibly nervous about it, but it was all very natural and fine. She’s a bear trap for dates and details, and she was just a complete gold mine. We got done and I said, “You’ve been really gracious with me, and really helpful, and I don’t really understand why.” She said, “You don’t remember this either, but we left it nice, me and you.”

With the mother of the kids, I hadn’t seen her in 10 years. There’s this miserable set of behavior that neither of us wants to own. Coming up with a common version of events with her was, um — yeah, it was ugly. It was painful. Oddly enough, though, she’s fine with the book. The Web site has her video on it, and a note from her. Her main concern about the book was that if that history got laid out our children, Erin and Meagan, wouldn’t want anything to do with her. It was precisely the opposite. It put her behavior in a context where they could understand it better. It seemed to help their relationship.

That’s something tangible that you accomplished, right there. That has an accidental selflessness to it. That might have been one of the best things you could do for her.

Well, I got 1,200 e-mails when an excerpt of the book ran in the New York Times Magazine, and a lot of them were from people seeking recovery. There’s the question of what really is hopeless: a thug, friendless and jobless, who 15 or 20 years later has what I have. That’s sort of a powerful and wonderful message. I’d like to think, even though there’s all this dark, terrible stuff in the book, that the clinical, classic redemptive uplift, the hug at the end, is there and real. I believe in recovery. I believe in the fundaments of recovery. Part of the gesture of the book, all gooey stuff aside, is an effort to give back. And yeah, I might have settled some things personally along the way.

Like so many people that are going to read your book, I have my own history with this stuff. I was probably doing coke when we hung out in Boston in 1994.

And you never shared! You kept going to the bathroom — I just thought you had a cold at the time!

I was deep in the minor leagues compared to you, but I had a close friend in San Francisco, my main drug buddy, who did a lot of that crazy stuff you did. He pawned his wedding ring to buy crack. He traded his car for crack.

You see people do all those things that your friend did and you wonder: What is with that guy? That’s why I tried to keep it really basic. There’s something sort of mysterious, almost a kind of possession, that’s under way, and I tried to get under that. You don’t start out deciding to be a complete raving maniac. It happens incrementally. It’s fun, and then it’s not.

Going back to the competing currents in your book, there’s this difficult and somewhat embarrassing section late in the story, when you have a relapse. In the early part of this decade, you started drinking again, and you suggest, very briefly, that you did some cocaine too.

Yeah, that’s true. Probably twice, I guess.

You wound up getting two DUI arrests …

I had one Driving While Impaired, which is not legally drunk, and then a classic DUI, like a .20 or something like that. Bad. Bad. Dangerous.

And that last arrest was relatively recent, like three years ago.

Yes. It was arrogance, boredom, I don’t know. A friend of mine was reading the book and said it sounded like classic midlife crisis. Not much more glamorous than that. I think that’s true. I was a little bored, so it wasn’t the office affair or the red convertible. It was “I’ll pour whiskey all over this and see how it goes.”

Unfriendly readers may well ask, “Why should we believe this guy about anything? He spent 14 years sober and got drunk again and nearly killed his family in a car accident? So why’s he telling us it’s all going to be OK?”

I didn’t say that. That’s bullshit.

I’m projecting that onto the reader.

No, you’re projecting that onto me and that’s bullshit. I never say anything like that. Let’s talk about what’s real. And what’s real is: Why would they believe anything I say? Because I document it.

OK, let’s make it specific. After that, why should we believe you’re going to stay sober?

I say in the book that I could be drunk tomorrow or shooting dope the next day. There’s no implicit sort of promise. I say that I like being normal, that I like the fruits of normalcy and that I’m happy. I never made a commitment. You need, or the reader needs, to say, “And everything will be hunky-dory forever.” That is not the message of my book. It’s a cautionary tale in that regard.

When you spend three years looking into the wreckage of your past, it tends to help you keep focused on the next right thing. It’s been great for my overall health and chemical well-being to work on this book. It may have been part of why I did it, I don’t know. There’s millions of people who get and stay sober without writing books. I think I had been busy forgetting some things. I thought I could be this tidy little suburban drunk, and in fact I’m not. I’m a lunatic. I’ve got the allergy to beverage alcohol.

Addiction remains pretty hard to understand for people who don’t have it. I was more like the kind of yuppie dilettante you’ve seen a lot of, I’m sure. I smoked crack one night with my buddy — the one I talked about earlier — and then of course we went right out and bought some more. And it was great. And after I finally got two hours of sleep I got up and said, “If I ever do that again, that’s the road to hell.”

I think that’s a really, like, common and sensible response, and I think that’s the vast majority of people. You’re essentially mainlining a Schedule 1 narcotic right into your bloodstream, and most people get a sense of that lurid ambush and they go, “No. I’m not the one.” For a certain number of people, me included, it’s like, “That was the best thing ever. Let’s do it again.” Why? Well, something that completely and totally rings the bell on every endorphin you have — why would you do that again? You got me. That’s totally mysterious!

Do you actively regret having done all that stuff? Or is that not a valid question for you?

I regret a lot of it, yeah. I would never have said that before I did this book. I love the book and I’m really proud of it and happy with it. I don’t really like the story very much. I don’t like the guy in it or the things he does. I don’t feel any sort of junkie pride in any of it.

That’s the part of the book that turned out after I wrote it. I began to see myself through other people’s eyes. Just like, wow, that guy really is an asshole. I think of myself as, you know, a single parent who got my kids off welfare, lived through cancer, did this, did that, got really good jobs. I don’t tend to focus on the other things. And so, yeah, I’ve had my moods with it. It’s given me the darks a few times.