The Democrats' last two vice-presidential picks, Joe Lieberman and John Edwards, have not -- to put it gently -- aged well politically. But Barack Obama's selection of Joe Biden may prove that the third time in this decade is the charm.

At first glance, the anointment of the 65-year-old Biden, who was first elected to the Senate from Delaware when Richard Nixon was in the White House and Obama himself was 11 years old, represents the triumph of experience over hope. But it also underscores that Obama meant it when he said a few days ago in a TV interview that he wanted a vice president "who is going to be able to challenge my thinking and not simply be a yes person when it comes to policymaking."

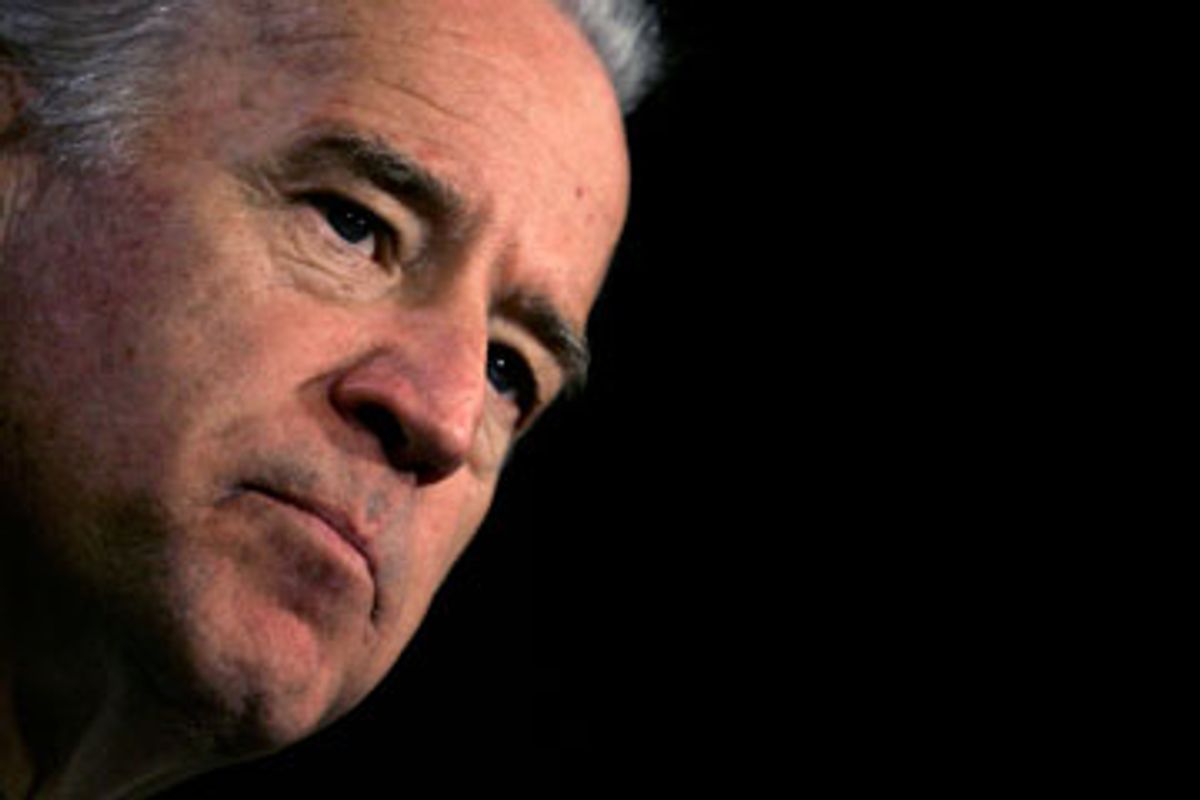

Joe Biden is nobody's "yes person." He is both the Democrats' most compelling spokesman on foreign policy (despite his 2002 vote to authorize the Iraq war) and a smile-and-a-beer glad-hander who campaigns with brio among blue-collar voters. There is a scrappiness and a forthrightness to Biden that make him an outsider despite his establishmentarian perch as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. As David Wilhelm, a former chairman of the Democratic National Committee with strong ties to Biden, said Saturday morning, "He's the guy who, for all his Washington experience, is not beloved by the K Street crowd [of lobbyists]. He's told too many people what he thinks."

There was a popular theory that Obama was too caught up in his own history-making narrative to risk choosing a running mate whose career points up the Democratic nominee's experience gap. The front page of the Washington Post Web site makes this clear by describing the Biden choice as a "move aimed at shoring up his foreign policy credentials."

But by going with a strong figure like Biden, Obama made a statement about his own self-confidence. It suggests that Obama has been taking to heart the lessons about Abraham Lincoln's style of governance in Doris Kearns Goodwin's "Team of Rivals" rather than merely using the book, which he often refers to, as a campaign prop.

For all the "I've Got a Secret" gamesmanship of the Obama campaign, the actual announcement of Biden's selection had all the grace of a 7-year-old learning how to ice-skate. When the Obama high command in a show of hubris promised that the campaign would text-message the V.P. secret to its loyal supporters before anyone in the press learned the hush-hush name, it never anticipated a 3 a.m. text message going out several hours after the media had confirmed the Biden news. But unless the second-banana choice turns out to be on a par with Dan Quayle, few voters are apt to remember the rollout by the time the convention is over.

John McCain's campaign was quick to go on the air with a TV ad quoting Biden's remarks in a campaign debate suggesting that Obama was not ready to govern. But such gotcha moments are a risk that accompanies putting any presidential also-ran on the ticket. (A safe bet: The Obama campaign has a full arsenal of Mitt Romney clips to use against McCain.)

The Obama vice-presidential talking points stress that Biden is not part of that derided species called "Washington insiders" because he takes the train home to Wilmington, Del., every night the Senate is in session. Rarely has a politician's route home been such a political selling point, but in Biden's case it speaks to a larger biographical truth.

Biden established this unorthodox routine to be with his two young sons after his wife and infant daughter were killed in a car crash just a month after his 1972 upset victory to the Senate. Biden's oldest son, Beau, now the attorney general of Delaware, is scheduled to be deployed to Iraq with his National Guard unit in October. "When you think about Joe Biden, you think about family," said longtime Delaware state Sen. Harris McDowell. "Everything starts with family with Joe."

But Biden is also a man of the Senate, a link to the days when legislative giants whose names now adorn office buildings sat around sipping bourbon and branch water. At a political fundraiser on Martha's Vineyard last month, sponsored by the Democratic Senate Campaign Committee, Biden regaled guests with a comic account of being a junior senator in the 1970s listening to old Southern patriarchs -- including arch-segregationists like Mississippi's James Eastland -- retell their favorite political stories, some designed to shock liberal Northerners.

Ted Kaufman, who ran Biden's Senate staff for two decades, acknowledges that these bygone Capitol Hill days left a permanent impression. "I've never met somebody who is both able to stick to their principles and yet negotiate with anyone from Strom Thurmond on the crime bill to Jesse Helms on the chemical weapons treaty," he said. Kaufman points out that the same desk used by Georgia Sen. Richard Russell to preside over meetings of the anti-integration Southern Caucus during the 1950s and 1960s now resides in Biden's Senate conference room. It passed from Russell to Mississippi's John Stennis -- a Southerner who adapted to the modern civil rights era -- to Biden.

The cable TV networks and Republican spokesmen marked time before the official V.P. announcement by harking back to a 1987 Biden brouhaha when the Delaware senator derailed his first presidential bid by quoting in an Iowa debate an elaborate autobiographical passage from British politician Neil Kinnock without attribution. (A conservative blog Saturday heralded a Time magazine article about the plagiarism flap that I wrote at the time.) But Biden in many ways has matured as both a politician and a person since that star-crossed campaign. A rueful Biden, in the midst of his most recent presidential campaign, told me in an interview that his big mistake in 1987 was running because "I was a better candidate than the other people -- and not because I was ready to lead the country."

It turned out that this time around Biden may have been a better leader than a presidential candidate, since he burnished his reputation while winning only 1 percent support in the Iowa caucuses. Once Obama made the political calculation that the personal discomfort of putting Hillary Clinton on the ticket more than outweighed the potential electoral gains, the nominee needed a way to justify his decision to her fervent supporters. Picking a first-term governor like Virginia's Tim Kaine or a political unknown like Texas Rep. Chet Edwards (who had a brief media flurry this week) would have seemed like an anyone-but-Hillary rebuff, especially since the V.P. choice will speak the Wednesday night after Clinton's name is put in symbolic nomination.

Biden may give the Obama campaign a few anxious moments worrying that his tongue may get ahead of his thought processes. But no one -- not even the most loyal Hillary acolyte -- can challenge Biden when it comes to experience. Of course, Biden has experienced everything in presidential politics -- embarrassment (Kinnock), abject defeat (2008) and now the elevation to the national ticket. As Ted Kaufman said with glee Saturday morning, "When I think of where we were in Iowa and where we are now, this is great."

Shares