Kevin Rafferty Productions

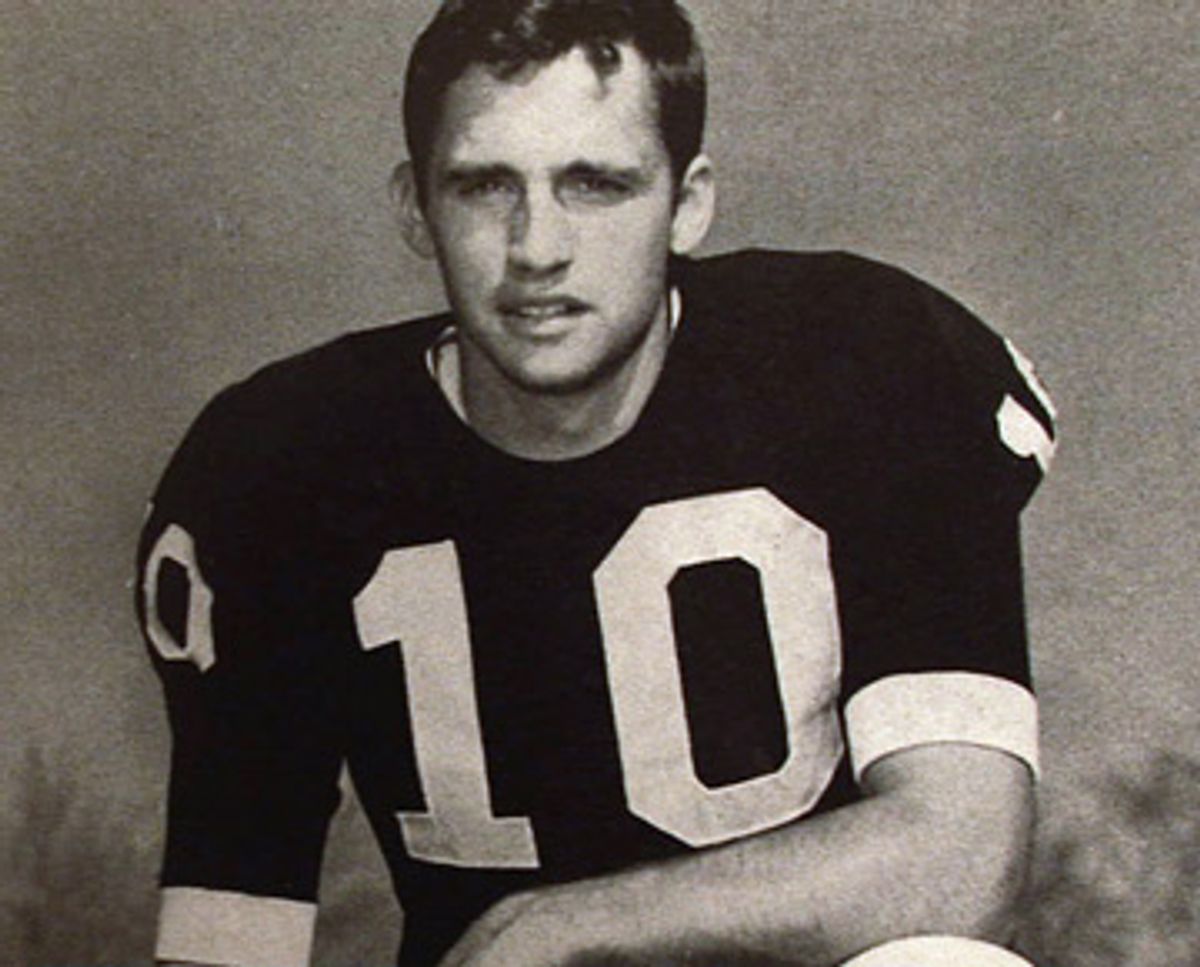

Brian Dowling, captain and quarterback of the 1968 Yale football team, in "Harvard Beats Yale 29-29."

I'm sure that football fans in the southern and western seven-eighths of the country would dispute the point vigorously, but for a certain Northeastern upper-crust sector of American society, no single event in college gridiron history comes close to the legendary status of the Harvard-Yale game that occurred almost exactly 40 years ago.

It almost goes without saying that it's an unfair standard. There have been other memorable games -- between USC and Notre Dame, Ohio State and Michigan, Alabama and Auburn -- that far more people attended and passionately cared about. But none of them occurred between America's two most elite educational institutions in a year of multiple assassinations, widespread campus uproar and social turmoil, and in a year when both teams (defying their long traditions of academic excellence and athletic mediocrity) were undefeated. And as the title of Kevin Rafferty's film about the 1968 game, "Harvard Beats Yale 29-29," may suggest, few sports events have ever ended in such an improbable and dramatic fashion.

Rafferty draws his title from a famous Harvard Crimson headline the morning after the game, and if it seems inexplicable at first glance (or at fourth), well, you've got to see the movie. To his immense credit, Rafferty stays focused on making a documentary about a famous football game, and takes a very light touch with any allusions to wider social significance. There's no footage of antiwar demonstrators in Harvard Yard or ROTC recruits marching through the streets of New Haven, although it's made clear that one of the factors at work in the rivalry was the perception that Harvard was an ultraliberal campus and Yale a conservative bastion. One of the Harvard linemen (future Oscar-winning actor Tommy Lee Jones, in fact) was roommates with a Tennessee senator's son named Al Gore; one of the Yale linemen was roommates with a Texas congressman's son named George W. Bush. (Want more? Yale fullback Bob Levin was dating an aspiring actress and Vassar student named Meryl Streep.)

Rafferty's technique is deceptively simple, and disarmingly effective. He shows large chunks of the charmingly old-fashioned 1968 game broadcast (from Harvard's TV station), while mixing in interviews with the surviving players, at first an interchangeable roster of hale, hearty and universally white lawyers, bankers, businessmen or academics in their early 60s. (Yale running back and future Dallas Cowboys star Calvin Hill was the only prominent African-American on either team, and his absence from the film is mysterious, given that he's still alive and operates a sports-consulting business.) Gradually the story of the game and the individual stories of the men who played in it -- legacy blue-bloods, scholarship kids from South Boston, Midwestern farm boys who'd never been to the East Coast before going to college -- wrap themselves around you, and you come to understand why it was such a powerful and peculiar event.

With Hill and quarterback Brian Dowling running the show, Yale was a nationally-ranked team that had bulldozed all Ivy League opposition, while Harvard had a ragtag bunch of players, in what was supposed to be a rebuilding year, who had won all their games apparently by chance. Hill was about to become the No. 1 pick in the National Football League draft, and Dowling -- the basis for B.D., the football star in classmate Garry Trudeau's "Doonesbury" comic strip -- hadn't played in a losing game since middle school. The Elis dominated the first half, quieting the big crowd at Harvard Stadium, and went into the locker room loose and confident, ahead 22-6. (Harvard scored a late touchdown and missed the extra point; as Tommy Lee Jones observes, if they'd made that kick the whole thing might have ended differently.)

As the game grinds on toward its culmination, with Yale seemingly in control (when Yale fans got tired of chanting "We're number one!" they began taunting the home faithful with chants of "You're number two!") but never quite delivering the knockout blow, all those faceless white men begin to become individuals. The beefy Levin ruefully reflects on his critical fourth-quarter fumble, one of five Yale fumbles that day. Yale defensive back Mike Bouscaren admits frankly that he was hoping to drive Harvard quarterback Frank Champi out of the game with a late hit, one of four or five crucial mistakes that cost Yale a certain victory.

With less than three minutes left, Yale was leading 29-13 and driving toward what looked like a decisive touchdown. Then Levin coughed up the ball deep in Harvard territory, and as many of the players remember it, the game became a dreamlike experience, one in which everything went right for Harvard and wrong for Yale: Penalty calls (both justified and questionable), missed defensive assignments, a botched on-side kick and a series of inspired improvisations from Champi, an awkward career backup with few friends on the team, who had been thrown into the game in desperation. (As one of his teammates observes, Champi seemed more like a linguistics professor than a football player. He would quit the team the following year, and never play football again.)

What happened then? Harvard scored 16 points in the last 42 seconds, to "win" a game that ended in a tie. (There were no tie-breaking overtimes in football at the time, and it's a good thing too. As several players note, if one or the other team had won, no one beyond the players and a few diehard fans would remember the game today.) That event on Nov. 23, 1968, didn't have anything to do with MLK or RFK or LBJ or the Chicago protests or the Vietnam War; it was a competing headline, a distraction from those things.

Rafferty, who was a Harvard undergrad at the time, renders the game a vivid and compelling experience even if (like me) you're not from the Northeast, didn't go to an Ivy school and don't give a crap about football. Social significance? I don't know about that. But "Harvard Beats Yale 29-29" is a ripping good yarn, like a Fitzgerald short story rewritten by John Updike, with an uproarious, impossible Hollywood ending.

"Harvard Beats Yale 29-29" is now playing at Film Forum in New York, with more cities and DVD release to follow.

Shares