For sheer number of innocent people exterminated under an infamous regime, Hitler is no match for Stalin. Yet our fascination with the fiery, scary Führer as "the incarnation of absolute evil," as Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel once called him, far surpasses our interest in practically all other hateful villains in modern history. In his highly imaginative novel "Winnie and Wolf," prolific British novelist and historian A.N. Wilson has taken an intriguingly dispassionate look at Hitler's inner circle. The novel, which came out in the U.K. last year, was nominated for the Man Booker Prize. Despite this high level of acclaim, readers may wonder why Wilson would bother taking a sober, realistic look at Hitler and thereby risk humanizing him. But among Wilson's 35 books is a biography of Jesus that is mostly about the impossibility of writing a biography of Jesus; Wilson is not one to back down from a challenge.

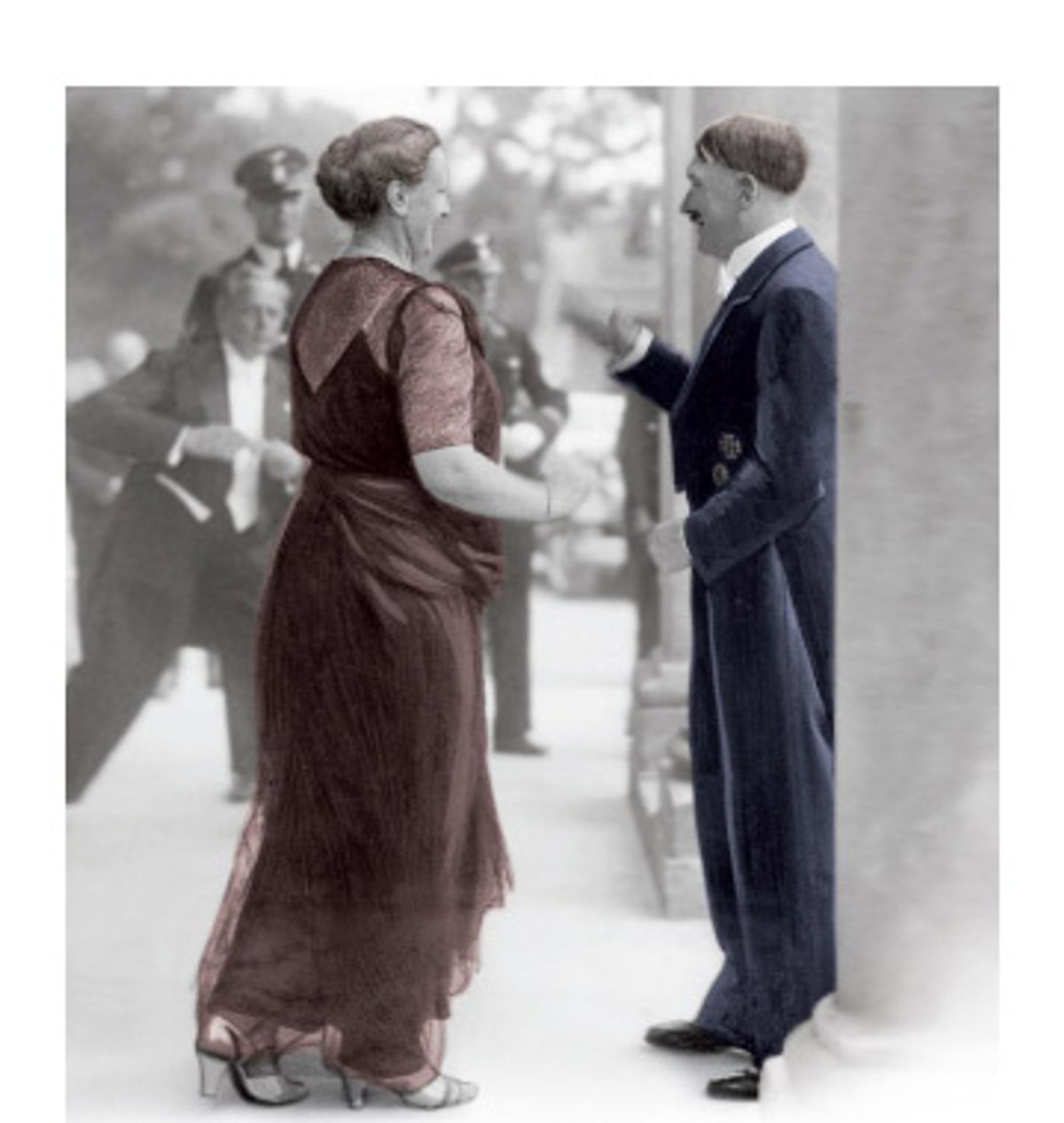

Hitler's legacy is so repugnant that even his surviving relatives fiercely guard their privacy and have mostly changed their surname, despite any profit they might make from sales of their famous relative's prison memoir "Mein Kampf" or hawking artifacts connected to the Third Reich. For a rational member of society to speak well of the tyrant in public is to create an outrage. One person who famously did so toward the end of her life was Winifred Wagner, wife of Richard Wagner's son Siegfried, who had a very close friendship with Hitler, or, as her family referred to him, "Uncle Wolf." Winifred Wagner claimed to despise Hitler's politics and treatment of the Jews, and saved the lives of various prominent Jewish people through her sway over the chancellor, but she defended her personal relationship with Hitler until as late as 1975, in a controversial five-hour interview she gave to German film director Hans-Jürgen Syberberg.

Wilson's novel seizes on the Wagner family's intimacy with Hitler and re-creates the atmosphere of high culture and low deeds around Bayreuth, the site of a yearly festival of Wagner operas -- and Hitler's favorite retreat -- in a voice whose serious tone (backed by exhaustive research) lends remarkable credibility to the novel. Through the narration of Wagner's assistant, Wilson gives readers an unsettling inside look at a side of the über-fascist we have rarely dared to consider since the end of World War II -- the opera lover who, despite the madness and destruction he unleashed on the world, was in the end still human, even if most would rather resign him from the human race.

Though the real Winifred has denied that she and Hitler ever had a sexual or romantic relationship, Wilson's book operates on the premise that the two carried on a clandestine affair for many years, one that resulted in a secret love child. Like Winifred herself, who was an English orphan adopted as a girl by a German family friend, the child is quickly given up for adoption. But Winifred then encourages Siegfried's childless personal assistant, N-, the all but nameless narrator, and his wife, Helga, to adopt the girl. The novel takes the form of a letter that N- writes to this child, Senta, who saves the manuscript and puts it in the care of her Seattle pastor just before she passes away many years later.

N- has long nursed an unrequited obsession with Winifred, and so he doesn't mind when she urges him to adopt a particular child. He's curious about Hitler, but his encounters with the leader are usually mixed with moments of puzzlement or revulsion. He watches in confusion as Hitler tells a children's story in his characteristically passionate oratory, for example. At a rally, he stands with Hitler's entourage and hears one of the chancellor's rousing speeches punctuated by a flatulence as forceful as his rhetoric. It isn't until 1939, when Winifred concocts a scheme to have Senta present a bouquet to Hitler at a performance of "Gottedamerung," knowing that war might separate them for a long time, that N- can no longer deny that his daughter has been sired by the man whose National Socialists have begun to cause the mayhem that led up to the war -- the Beer Hall Putsch, Kristallnacht, the Night of the Long Knives, etc. -- and the woman he loves more than his wife. But for N-, these events unfold without the benefit of hindsight. He balances his uneasiness with German Nationalism, and justifies its anti-Semitism with the fact that the repressive party has brought pride and solvency to a country devastated and debased by the Great War.

Winnie herself is the best of all at self-delusion, and her reaction following the murder of Erich Röhm in 1934 is a microcosm of prewar German denial:

"With her seemingly unshakeable belief that Wolf personally would never condone any of the atrocities of his own regime, Winnie had rung him up in a temper ... There had been quite a lot of shouting at him -- not least because she was unable to believe that he had anything to do with the murder of Röhm and the others. 'I know that you would have insisted on a fair trial,' she told the telephone receiver."

If Wilson makes Hitler seem less monstrous, that's part of his point. He doesn't do so in order to apologize for Uncle Wolf's atrocities, but to warn us against denial. "Winnie and Wolf," though penned by a Brit, could be the last great cautionary tale of the Bush years, with their Patriot Acts, government surveillance and "black sites." In his passion to rescue Wagner's reputation from its association with Nazism, among other things, Wilson suggests that the Nazis saw what they wanted to see in his work (German nationalism) and reinterpreted it for their purposes. Unfortunately, this association has outlasted their brutal rule. Chillingly, "Winnie and Wolf," in a complex, rich and ambitious fashion, shows us how easily a leader's charisma can distract both naive individuals like Winifred and entire nations from his faults and crimes, even as he leads us into chaos.

Shares