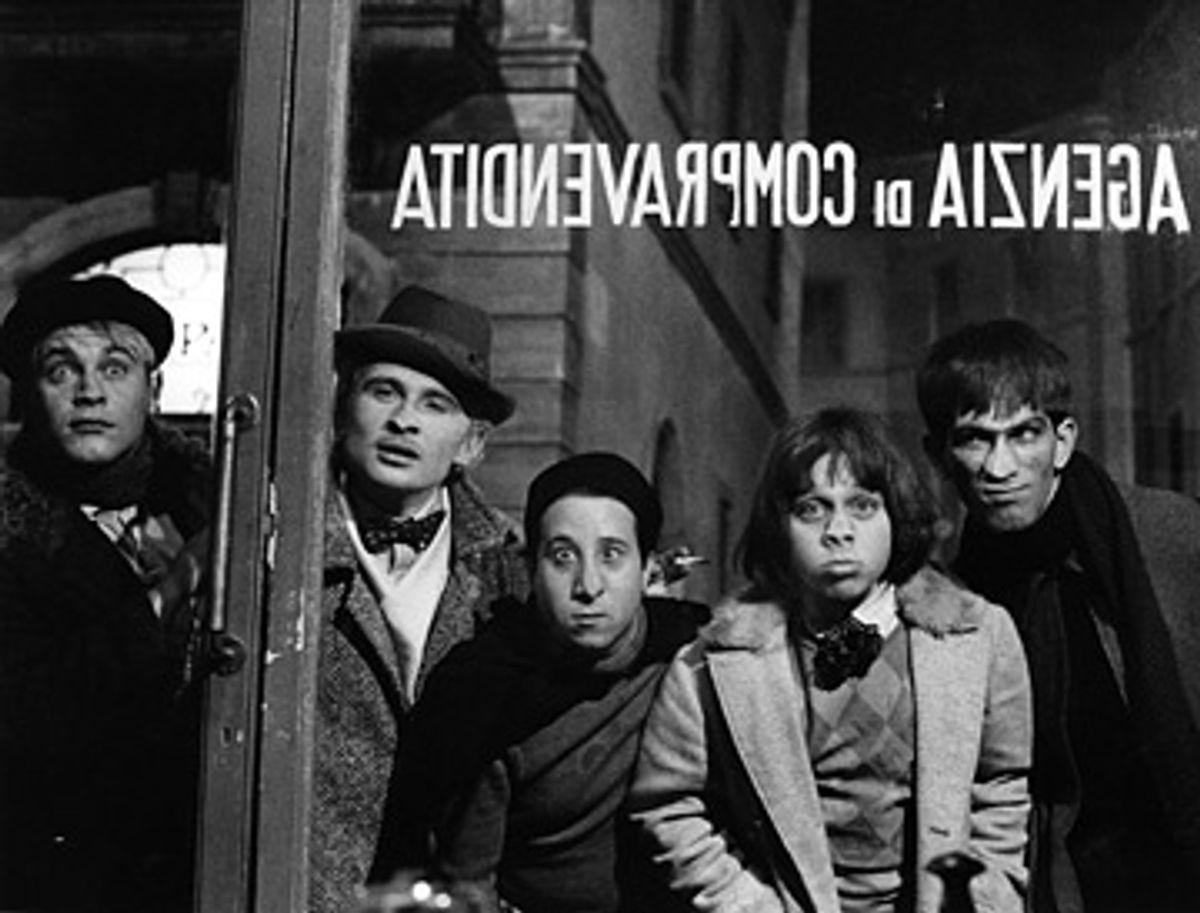

Janus Films

From left to right: Bruno Zanin, Luigi Rossi, Alvaro Vitali, Bruno Scagnetti, and Bruno Lenzi in Federico Fellini's "Amarcord."

Pitched somewhere between genuine childhood reminiscence and an outlandish, "Arabian Nights"-style collection of tales, Federico Fellini's 1973 "Amarcord" captures the great Italian director at the peak of his cinematic powers. Although it's undoubtedly not as "important" or as self-serious a picture as "8 1/2" or "La Dolce Vita" or "La Strada," "Amarcord" -- the word may signify "I remember" in the Romagnese dialect of Fellini's youth, although some experts regard it as an invention -- is a massively enjoyable entertainment infused with more than a little wry wisdom, pathos and mystery.

If you're pursing your lips disapprovingly and getting ready to ask whether "Amarcord," like most of Fellini's later movies, isn't simultaneously sentimental and sexist, here's my answer: It sure the hell is. Kids, dogs, wisecracking old men and well-proportioned female derrières take up a significant portion of screen time in "Amarcord," and the film's point of view never wanders far from that of Titta (Bruno Zanin), the desperately horny teenage boy in the seaside town of Rimini whose mom still has him in short pants. But it's all a question of what Fellini does with those ingredients and with that perspective, which is to create a highly complicated work of memory and fantasy, a grand, theatrical blend of comedy and tragedy that addresses both what he loved and what he hated about the provincial Italian character.

OK, there is the legendary topless scene that brings Titta up close and personal with the bodacious town tobacconist (Maria Antonietta Beluzzi), a Russ Meyer-worthy moment that no doubt helped propel "Amarcord" to international hit status -- and to a 1974 Oscar for best foreign film. But the cigarette girl's enormous breasts and Titta's encounter with them, you might say, are only as real as the gigantic spectral ocean liner the whole town rows out to see, or the 28 Arab concubines serviced in one night by the fruit merchant, or the night of romance with a handsome prince that gives the much-lusted-after town hairdresser (Magali Noël) the nickname Gradisca ("whatever you desire").

Just re-released in an eye-popping new 35 mm color restoration, "Amarcord" is a lot more than a sweet-natured erotic fantasia about bucolic existence in a bygone era. That era, after all, was the Fascist dictatorship of the 1930s, which Fellini depicts as a willfully stupid exercise in groupthink that swept up the entire population and was only beginning to show its sinister underbelly. (Titta's father, played by Armando Brancia, is virtually the town's only anti-fascist holdout.) The enormous talking flower arrangement in the shape of Il Duce's head is often cited as an element of Fellini-esque fantasy, but I'd be willing to bet he didn't invent it. (OK, maybe the talking part.)

Even in a film as whimsical, as loving and as devoted to pleasing the audience as "Amarcord," Fellini is a vastly subtler and bigger artist than the many subsequent filmmakers who've tried to imitate him, and who typically seize on the sticky-sweet syrup and bon-vivant erotica, while avoiding the vinegary aftertaste. He always understood that the storyteller's magical incantations, which allow the past to live again, bring back the things that still hurt and the things that never made sense along with the joys.

"Amarcord" is now playing at Film Forum in New York. It opens Jan. 2 in Chicago and Seattle, Feb. 13 in Los Angeles, Feb. 20 in San Diego, March 13 in Washington, March 27 in Minneapolis and April 17 in Philadelphia, with other engagements to be announced. It's also available on DVD (although not yet in the newly restored version) from the Criterion Collection.

Shares