On Thursday, after months of parliamentary wrangling, Iraq's three-man presidential council finally approved the U.S.-Iraq security pact, known as the Status of Forces Agreement. The pact requires all U.S. troops to leave Iraq by the end of 2011, with all combat forces withdrawing from Iraq cities in six months. The pact is a milestone: It spells the beginning of the end of Bush's great Iraq adventure. But not surprisingly, no one agrees on just what it means.

The Bush administration and war supporters claim that the agreement is a great victory. Neoconservative pundit Charles Krauthammer declared in the Washington Post that the agreement represents "the single most important geopolitical advance in the region since Henry Kissinger turned Egypt from a Soviet client into an American ally." War opponents have cautiously welcomed its call for an end to the U.S. military presence in Iraq but remain skeptical about whether it really represents progress.

But most Americans have barely noticed the security pact. Like the solipsist's tree falling on the moon, wars only exist when you notice them, and the American people tuned out the Iraq war long ago. This is a troubling fact, because war is a vast and terrible thing, the most momentous action a state can undertake. Whether you're a war supporter or a war opponent, you should be paying attention. The end of the war that bitterly divided America, cost thousands of American lives and an estimated 3 trillion dollars and wrecked the Bush presidency is in sight, and no one seems to have noticed.

So as we approach the beginning of the end of this war, it's worth drawing up a report card. Not a final one -- it may not be possible to issue a final historical grade on Iraq for decades, or even longer. But it is possible to make some judgments. The Iraq story isn't over yet, and whether we like it or not, we are deeply implicated in its outcome. When we invaded and shattered the country, we assumed a large measure of responsibility for its fate.

First, all sides, pro-war or anti-war, should agree that anything that helps Iraq and the Iraqi people is a good thing. The Iraqis should not be pawns in anyone's political game. George W. Bush's war may have been a catastrophic mistake, illegal, immoral and destructive in every way. But if something takes place on Bush's watch that helps the Iraqis, we should support it.

From that perspective, the security agreement does indeed provide some grounds for optimism that the next chapter in Iraq's story may not be as disastrous as the one written by Bush. That outcome is far from guaranteed. Iraq could still fall back into sectarian and ethnic chaos, and a thousand other disastrous or unpleasant or merely mixed outcomes could await it. The pact is unpopular with many Iraqis for different reasons, and it was only approved after massive U.S. arm-twisting and threats -- even though Bush had to make major, humiliating concessions in it. Nor is it a completely done deal: The Iraqi people will have their chance to approve or reject the agreement next June.

Still, the very fact that the Iraqi government has for now agreed on something -- anything -- is a good thing. Years ago, prescient analysts pointed out that the best and perhaps only way for the U.S. to exit Iraq would be if a relatively palatable nationalist leader kicked us out, thus salvaging Iraq's national honor and perhaps allowing both sides to emerge with at least a few shreds of dignity. In effect, that is precisely what has happened.

Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki is at best barely palatable. He is determined to turn Iraq into a Shiite Islamic state, and he has yet to try to reconcile with Iraq's Sunni minority. But after the horrific civil war unleashed by the Golden Mosque bombing in 2006, even having a dubious, Iran-leaning zealot like Maliki in shaky control is better than anarchy.

While the security agreement provides reason for some cautious optimism, the claims made about it by the Bush administration and war supporters are wildly exaggerated. In a speech at the Brooking Institute's Saban Forum on Friday, President Bush declared that "Iraq has gone from an enemy of America to a friend of America, from sponsoring terror to fighting terror, and from a brutal dictatorship to a multi-religious, multi-ethnic constitutional democracy. Instead of the Iraq we would see if a Saddam Hussein were in power -- an aggressive regime vastly enriched by oil, defying the United Nations, bullying its Arab neighbors, threatening Israel, and pursuing a nuclear arms race with Iran -- we see an Iraq emerging peacefully with its neighbors, welcoming Arab ambassadors back to Baghdad, and showing the Middle East a powerful example of a moderate, prosperous, free nation."

Bush's statement, not to put too fine a point on it, is ludicrous. Polls show that most Iraqis regard Americans as occupiers, not liberators. In a 2006 poll, 61 percent said they approved of attacks on U.S. troops. The Iraqi government only agreed to the security pact -- which Iraqis call "the withdrawal agreement" -- because it ordered American troops out of their country. At some point in the future, it is possible that Iraq may have normal diplomatic relations with America, but to assert anything more than that is unjustified.

As for Iraq being peaceful, moderate, prosperous and free -- sadly, none of that is true now, and of the prospects that it will become true in the future, all one can say is in'shallah (Arabic for "God willing"). Many things stand in the way: the lack of Sunni-Shiite reconciliation, tensions with the Kurds, and Shiite-Shiite rivalries. Muqtada al-Sadr remains a wild card: His powerful militia is currently standing down, but could be reactivated at any time.

In a best-case scenario, Iraq will end up a fairly unstable state more or less closely aligned with Iran, with unequal oil revenue distribution and aggrieved Sunni and Kurdish minorities, but at least still unified, not plagued by major sectarian violence and not a declared enemy of the U.S. In a worst-case scenario, the country would become a failed state, descend again into violence on the scale of the civil war of 2006-2007 or worse and be a haven for jihadists and an open sore in the Middle East.

No possible outcome, not even Bush's hand-tinted Hallmark Card vision of a peaceful and prosperous Iraq, could ever justify the devastation we have wrought. Forget our geostrategic goals. Even if we had achieved those goals, which we have not (Juan Cole has a must-read refutation of the absurd claims and twisted history in Bush's Brookings speech), the cost of the war would make it morally unacceptable.

Credible researchers have estimated that as many as a million Iraqis have died as a result of the U.S.-led invasion -- a figure the mainstream U.S. press seems afraid even to mention, although many media outlets blandly use the absurdly low estimate "tens of thousands." If one conservatively assumes that the real figure is 500,000 (below the 650,000 estimate put forward by another respected study), or even the Iraqi Health Ministry's figure of about 200,000, then it is clear by any ethical standard that the war was not justified.

Yes, Saddam Hussein was a monstrous tyrant who was responsible for the death of hundreds of thousands of his people. But most Iraqis say that their life was better under Saddam than under the Americans. In any case, it's not a matter of comparing body counts under Saddam and the U.S. occupation and saying that whoever killed less is better. You can't start a war that kills a large percentage of a nation's population, forces millions more into exile, ignites a savage sectarian conflict whose wounds could exist for generations, destroys entire cities and then declare that what you've done is morally justifiable, let alone that it can be characterized as a "victory."

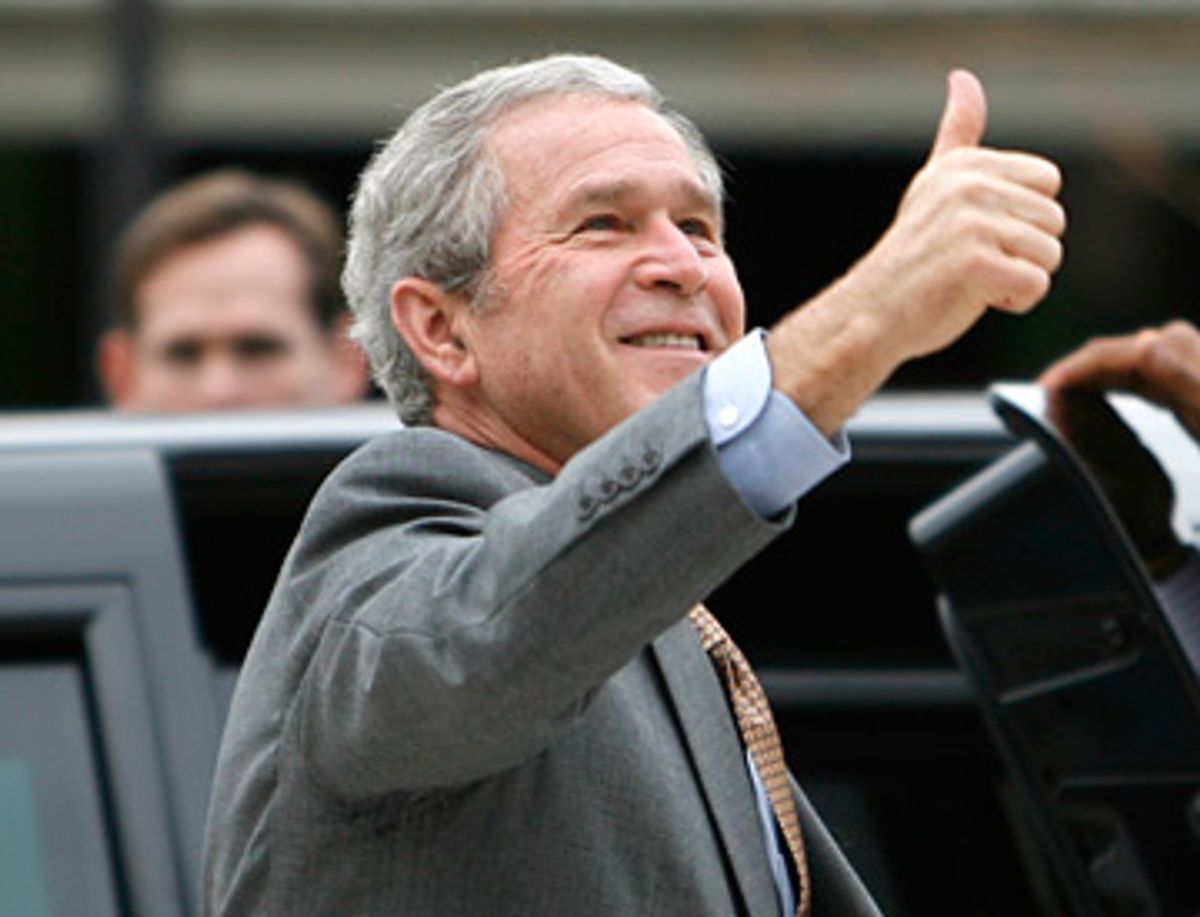

Bush himself seems at some level to recognize that the war should never have been fought. In a bizarrely self-pitying and profoundly untruthful interview with ABC's Charles Gibson, Bush said he wasn't prepared to be a war president, said that the biggest disappointment of his presidency was the "intelligence failure" that he claimed led him to believe that it was too risky to allow Saddam Hussein to remain in power and admitted that if he had known that Saddam did not have WMD, he might never have started the war. Bush is probably confused and self-deluding enough to actually believe that the prewar intelligence really was bad, and not that his administration cooked it. But the triumphalist rhetoric of the legacy-burnishing statesman who held forth at Brookings cannot conceal the diminished, chastened man behind the curtain who in some part of his brain realizes that the war was a dreadful mistake that ruined his presidency.

What's done cannot be undone. But is there anything America can do now to maximize the chances of a favorable outcome for Iraq and the Iraqis?

The crucial issue is how and when the U.S. should withdraw from Iraq. President-elect Obama is under increasing pressure to abandon his pledge to remove most U.S. troops in 16 months. War supporters and even some war critics argue that he could destroy the progress that has been made if he withdraws troops "irresponsibly." If there were compelling evidence that that were true, then even those who opposed the war should reject timetables and support a conditions-based exit. But the preponderance of the evidence suggests that we should follow the security agreement and leave Iraq as soon as possible -- lock, stock, barrel and bases.

If we stay in Iraq, we are essentially acting as a referee, mediating between clashing sides and, if necessary, attacking them in an attempt to control the outcome of the game. The problem is that we do not have the ability to control that outcome. There are too many variables, and the balancing act we have to perform is too complicated. Our presence may deter some factions from attacking other ones, but it is inevitably going to result in our propping up whatever dominant faction promises the most stability. That faction, however, will be inherently artificial and illegitimate as long as we are its guarantor -- which means that it will not be stable. At the same time, our concern for minority rights will give the minorities no incentive to compromise. Ironically, our efforts to ensure a fair and equitable outcome will prevent such an outcome.

As Mideast expert Marc Lynch argued in Foreign Affairs, "improved security is making the government of Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki less likely to make meaningful compromises, since Maliki currently sees little downside to not doing so. The Iraqi government simply does not share American assessments of the negative consequences that would result from failing to achieve reconciliation. And as long as the U.S. military protects Iraqi leaders from the consequences of their choices, they are probably correct."

What is true for Maliki is true for all the other players. Neither the Sunnis, the Kurds nor the Shiites will see any reason to compromise as long as the U.S. is acting as a referee. The Shiites know that the U.S. has made its peace with Maliki and does not want him to fall, so they will feel free to take a hard line with the Sunnis. The Sunnis know that the U.S. will act on their behalf, as it did when it paid off the insurgency and turned it into the "Sons of Iraq," so they will not be interested in compromising. And the Kurds will make a similar calculation. Moreover, a continued U.S. presence will empower precisely those groups, like the nationalist Muqtada al-Sadr's Mahdi Army, that we do not want to encourage.

But no one can read the future. It is theoretically possible that the Bush administration and war supporters are right and that a prolonged American presence, combined with adroit diplomatic and economic sticks and carrots, will provide a breathing space for the political reconciliation that Iraq so desperately needs. The problem is that the administration has been saying this for five years, and there is still no reconciliation. (The much-touted surge did not produce reconciliation.) At this point, the burden of proof is on the defenders of a prolonged American presence in Iraq. And they don't have any compelling arguments.

The crucial test Obama will face in Iraq is what he does when violence inevitably flares. If he continues to withdraw U.S. troops, he will be heavily attacked by the establishment, including some of his own national security advisors, for "losing" Iraq. But if Obama keeps the U.S. troops in place, he will simply be giving radicals an incentive to keep attacking them and creating chaos in Iraq. The best-case scenario for al-Qaida is one in which the U.S. is permanently bogged down as an occupying force in an Arab country, unable to either win or to leave. And students of military history know that neither the U.S. nor any superior force can win a modern quasi-guerrilla war of attrition in an unfriendly occupied country: the tactics required to win are too harsh, and the cost too great.

From the beginning, the Bush administration always insisted that it would not set timetables for withdrawal, that only conditions would dictate when U.S. troops left. The new security pact represents a complete surrender by Bush on that point. Desperate to have some agreement to show, Bush disingenuously claims that conditions have improved enough to begin planning for withdrawal. But he wants to have it both ways: He claims that Iraq has made great progress, but warns that that progress is so fragile that we can't leave until some undefined line is crossed. Obama needs to cut through this endless, looping argument in which everything that happens, good or bad, can be used to justify keeping troops in Iraq.

The bottom line is that it is not in our power to control the outcome in Iraq -- and with our economy in the tank and our Army overstretched, we can no longer afford to keep trying. We cannot allow the unpredictable vicissitudes of Iraqi politics to hold 140,000 U.S. troops hostage forever. Especially not because the presence of those troops in the heart of the Arab world is a recruiting poster for jihadis.

We owe the Iraqis more than we can ever repay. And if staying in Iraq would be the best thing for them, we should do so. But there is little evidence to support that notion. In the end, only Iraqis can determine the fate of their country. And the best way the U.S. can help them do that is to leave.

Shares