New Yorker Films

An icon of independent cinema crumbled before the nation’s widening financial crisis on Monday, as New Yorker Films, owner of an unparalleled library of art-house films from all over the world, announced it was closing up shop after nearly 44 years. While the company had evidently been in distress for some time — it had sharply downscaled its theatrical operations, and its DVD releases were frequently delayed — the announcement still sent shock waves through the independent film world.

New Yorker was founded in 1965 by moviehouse proprietor Dan Talbot, who continued to run it, in partnership with co-president José Lopez, until the closing was announced Monday. In case you’re wondering, it has no connection with the New Yorker magazine, owned by Condé Nast. Talbot named the film company after the repertory cinema he then operated on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. (While that theater is long gone, Talbot still owns a majority share of the Lincoln Plaza Cinemas, another Upper West Side institution, which is unaffected by New Yorker’s closing.)

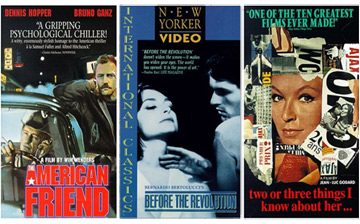

Bernardo Bertolucci’s “Before the Revolution” was the first film New Yorker distributed in the United States, and the hundreds of pictures that followed comprise such an illustrious list it’s difficult to pick highlights. Scanning the decades almost at random, here are a few I see: Jean-Luc Godard’s “2 or 3 Things I Know About Her” (1970), Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s “The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant” (1973), Werner Herzog’s “Aguirre, the Wrath of God” (1977), Wim Wenders’ “The American Friend” (1977), Jacques Rivette’s “Celine and Julie Go Boating” (1978), Errol Morris’ “Gates of Heaven” (1980), Louis Malle’s “My Dinner With André” (1981), Wayne Wang’s “Chan Is Missing” (1982), Chantal Akerman’s “Jeanne Dielman” (1983), Claude Lanzmann’s “Shoah” (1985), Eric Rohmer’s “4 Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle” (1989), Claire Denis’ “I Can’t Sleep” (1995), Emir Kusturica’s “Underground” (1996), Abbas Kiarostami’s “The Wind Will Carry Us” (2000) and Krzysztof Kieslowski’s epic “Decalogue” (made in 1989, but released in the U.S. in 2000).

New Yorker’s demise apparently stems from a bank loan taken out some years ago by now-defunct Madstone Films, the company’s former owner. To secure the loan, Madstone pledged New Yorker’s assets, meaning the DVD and theatrical rights to its library of more than 400 films, as collateral. According to an IndieWIRE story and other media reports, Lopez sent an email to New Yorker’s filmmakers over the weekend, informing them that the loan is now in default and the lender has foreclosed on New Yorker’s assets, which could be sold off as soon as next week.

In a broader sense, New Yorker’s long-term willingness to defy the marketplace realities of American film distribution never seemed like a sustainable business model. While the films listed above attracted at least some American viewers, New Yorker was worshiped in cinephile circles precisely because it often took on difficult and adventurous cinema that was destined to find almost no audience. Sometimes Talbot and Lopez seemed to be running an educational foundation under the guise of a for-profit business. In bringing films by African cinema godfather Ousmane Sembène, Chinese rebel Jia Zhang-ke, obscure American auteur Lodge Kerrigan and legendary French documentarian Chris Marker to a handful of American viewers they were undeniably performing a public service, but they surely didn’t make any money in doing so.

After the shock of the official announcement of New Yorker’s demise — which arrived midday on Monday, via the company’s Web site — began to subside, admirers and former New Yorker employees began to wonder what would happen next. “I firmly believe that this is merely the end of chapter one,” says indie distributor turned filmmaker Jeff Lipsky, who was a New Yorker exec in the ’80s and ’90s. “I’m refusing to accept the permanent demise of New Yorker Films.” Lipsky suggests that Lopez, who has been most active in running the company in recent years, may have a rescue plan in mind that will keep the New Yorker name and library intact under new ownership.

“What value is there in breaking it up?” Lipsky asks. “It needs the stewardship of somebody who knows where the bodies are buried in terms of the rights on each of these pictures, and who understands these delicate films and their audience. It would make no sense to anybody to break up that library.”

Ryan Werner, a vice president at IFC who says he has modeled his career path on those of Talbot and Lopez, generally agrees. “It makes no sense for somebody to say, ‘I’m taking “Jeanne Dielman” and the Fassbinder movies but not the Godards,'” he says. “The value of those films comes from 40 years of curatorial work, and I would hope that they all end up staying together.” The value of the New Yorker name, Werner says, may be mainly sentimental at this point, since it’s unlikely that younger film buffs have a strong association with the label.

New Yorker’s library would have obvious appeal to “an online distributor, a TV network or a DVD company,” Werner continues. Given that IFC is at least two and potentially all three of those things, and in recent years has assumed a commanding position in the distribution of foreign-language and American independent films, it might be the most logical potential bidder. Werner declined to speculate about that possibility, saying no corporate decision had yet been reached.

There are certainly other small, arty distributors that would love to own New Yorker’s catalogue, including Facets Video, Kino International and Koch Lorber Films, but those are marginal players in the video marketplace, and in the current financial crisis they don’t likely have cash to spare. For now, the fate of New Yorker’s famed film library seems to depend on a question voiced by South by Southwest Film Festival head Janet Pierson, who worked alongside Lopez and Talbot programming New York’s Film Forum in the early ’80s.

“For so many of us those films meant so much,” muses Pierson. “They shaped a generation of people who devoted their lives to independent cinema. Do they still have resonance? I have the question, without knowing the answer, about whether anybody still wants to see them.”