(updated below – Update II - Update III)

When Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Pat Leahy announced a couple of weeks ago that he intends to introduce legislation to create a “Truth Commission” to investigate Bush war crimes, it seemed to be the type of meaningless announcement for which Senate Democrats generally and Leahy specifically are known: nicely symbolic and pseudo-principled but ultimately entirely inconsequential (Leahy explicitly said he opposes prosecutions no matter how egregious is the evidence of massive criminality on the part of the Bush administration — i.e., the functional equivalent of a pardon for all Bush officials, gift-wrapped by Democrats like Leahy). But now, Salon‘s Mark Benjamin (who, just by the way, has a history of some truly great reporting over the last few years) reports facts that suggest the Commission might actually be more serious than that — and that’s true largely for one reason: Sheldon Whitehouse.

Leahy told Benjamin that the Senate Judiciary Committee is set to hold a hearing very shortly on the best way to structure the investigative body, and that they intend to announce that as early as today. More significantly, Whitehouse all but assured Benjamin that there would be a Commission created by the Congress to investigate these war crimes and used what the Beltway considers to be “shrill” language when describing its significance:

Still, regarding a potential torture commission, he told Salon, “I am convinced it is going to happen.” In fact, his fervor on the issue was palpable. When asked if there is a lot the public still does not know about these issues during the Bush administration, his eyes grew large and he nodded slowly. “Stay on this,” he said. “This is going to be big.”

Perhaps the most important fact reported by Benjamin was that it is Whitehouse who would “spearhead” the effort. Whitehouse is on both the Senate Intelligence and Judiciary Committees and thus knows more about these activities than has been made public. Critically, he is also a former federal and state prosecutor and thus instinctively considers lawbreaking to be wrong no matter who is doing the lawbreaking [a view one would think would be commonly held (since it’s sort of a foundational principle of that country) but is one that actually makes Whitehouse an anomaly among our political class]. His genuine passion to investigate these crimes is reflected in several speeches he has given demanding that these crimes not be “papered over.”

At least equally encouraging is Whitehouse’s recognition that Congress has the obligation to investigate these crimes regardless of whether Barack Obama wants to do so or is able (in light of the financial crisis) to spend time on this, and regardless of whether Obama approves or disapproves:

Whitehouse admitted he had not discussed the plan yet with President Obama, who has been notably wishy-washy on the notion since taking office. . . .

According to Whitehouse, current politics dictate that Congress should take the lead on establishing a torture commission. “When you look at the economic meltdown that [Obama] was left by the Bush administration, you can see why he would want to reassure the American public that he is out there looking at these problems and trying to solve them and not focusing on the sins of the past,” he said.

Whitehouse, however, predicted that Obama would not object to a torture commission moving forward in Congress. Besides, he said, “When push comes to shove, we are the legislative branch of government. We have oversight responsibilities. And we don’t need the executive branch’s approval to look into these things just as a constitutional matter.”

A re-establishment of an independent Congress that operates separate from, as a check on, and at times adversarially to the executive branch is at least as important as any other single political priority. Whether Senate Democrats would really proceed with a meaningful investigation even in the wake of emphatic White House opposition remains to be seen (as does the question of whether the White House would object), but at least Whitehouse is sounding the right notes here.

Having said all of this, Whitehouse, to his discredit, emphasizes — either because he believes it or because he perceives that saying so is political necessary — that the purpose of the investigative Commission will not be (and should not be) to make prosecutions ultimately possible. But a genuine investigation of the crimes committed by the Bush administration, once launched, could very well render prosecutions more likely regardless of whether the Senators creating the Commission wish that to happen.

The process of shining light on government crimes cannot always be controlled once it starts, especially if genuine investigative powers are vested in an independent Commission. When Obama recently embraced Bush’s State Secrets privilege and in other cases began aggressively trying to shield other Bush crimes (such as illegal eavesdropping) from judicial scrutiny, many suggested that the Obama administration’s motive is that it fears that any systematic disclosures — and especially any formal adjudication — of Bush lawbreaking will significantly increase the pressure on the Obama DOJ to commence criminal investigations, something it desperately wants not to do. Such fact-finding investigations can rile up public sentiment, unearth facts that would serve as the basis for prosecutions, and create a more favorable political climate for prosecutions. That was Scott Horton’s rationale in Harper‘s for why such a fact-finding Commission should be created as a necessary prelude to criminal prosecutions.

After all, if even more horrifying evidence of America’s war crimes under Bush/Cheney are systematically disclosed, along with formal conclusions that these acts were illegal on the part of our highest government leaders, then what justifications would there be for the Obama DOJ to turn away from all of that? It might be very difficult for them to do so. As Slate‘s Dahlia Lithwick put it in speculating about why Obama would embrace Bush’s State Secrets theory in order to deny torture victims their day in court:

[B]y keeping the worst of the Bush administration’s secrets hidden, the Obama Justice Department can defer awkward questions about prosecuting the wrongdoers. In his press conference Monday night, Obama repeated his mantra that “nobody is above the law and if there are clear instances of wrongdoing, people should be prosecuted just like ordinary citizens. But generally speaking, I’m more interested in looking forward than I am in looking backwards.” The principle once again is that Obama is for prosecuting Bush administration lawbreaking only when proof of such lawbreaking bonks him on the head. All the more reason to keep it out of sight, then.

I think she’s right about that. But the converse is that by disclosing the Bush administration’s secrets and shoving Americans’ faces in the fact that our government leaders deliberately violated our most serious domestic laws for years and clearly committed war crimes, it makes it that much more difficult for the Obama DOJ to “defer awkward questions about prosecuting the wrongdoers.”

It’s true that those who create the Commission might — as Whitehouse suggests – intend it to be a substitute for prosecutions rather than a precursor to them. It’s also possible that the Commission can be designed merely to placate those who are demanding that something be done, and — if immunity is doled out to high-level Bush officials — it could simply whitewash these crimes and even make prosecutions impossible. But it’s just as possible that once an independent body is created with real subpoena power and an authentic mandate to dig and disclose, it could turn into a Frankenstein: capable of doing damage far beyond what its creators intended.

Whatever else is true, for those who want to see Bush officials held accountable for the crimes the way that ordinary Americans mercilessly are: disclosure is preferable to ongoing concealment; an investigative body is preferable to inaction; formal conclusions about whether lawbreaking was ordered at the highest level is preferable to ongoing official silence; and a Commission that has the potential to lead to prosecutions is preferable to an explicit policy from the Obama administration that no prosecutions will take place.

UPDATE: Apropos of nothing in particular, this is a remarkable testament to the limitless ability of the human brain to perceive reality in a frighteningly distorted manner.

UPDATE II: Both Sen. Whitehouse and Sen. Leahy spoke today on the Senate floor to argue for the creation of an investigative Commission. The text of their speeches is here, and a video of Whitehouse’s speech is here.

UPDATE III: In an interview to air tonight with Rachel Maddow, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi suggested that Leahy Truth Commission was inadequate because certain features — including the granting of immunity — could foreclose criminal prosecutions, which Pelosi expressly advocated. The surprising details are here.

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, on the Senate floor, today:

“To Fix Damage Left by Bush, We Must Learn the Truth”

Mr. WHITEHOUSE. Mr. President, during my brief tenure so far in the Senate, the Judiciary Committee has confronted many difficult issues – battles over judicial nominations, complex legislative matters, the historic investigation into misdeeds of the Bush Administration’s Department of Justice.

In that process, the Committee saw U.S. Attorneys fired for political reasons, we saw the Civil Rights Division run amok, we saw declassified legal theories asserting that the President can secretly ignore his own executive orders, we saw unprecedented politicization of a noble Department, and, of course, we saw those Office of Legal Counsel memos approving interrogation techniques long understood – long known – to be torture.

Fortunately, throughout that time, Chairman Leahy sought answers. His efforts were even-handed but unyielding. We know so much of what we know now because Patrick Leahy was satisfied with nothing less than the whole truth. Today, his work continues, and I want to speak in support of his efforts.

Mr. President, the backdrop to this is of course a grim one. Over and over as I travel around my state of Rhode Island, I hear from people facing challenges that seem almost insurmountable; challenges that President Obama spoke about in his address to Congress yesterday. Every day, it gets harder and harder to find a job, to pay the bills, to make ends meet. Every day, it seems more difficult to see a way out.

The Bush Administration left our country deeply in debt, bleeding jobs overseas, our financial institutions rotten and weakened, an economy in free fall. This is the wreckage we see everywhere, in shuttered plants – as my colleague from Pennsylvania sees at home so cruelly – in long lines, and in worried faces.

But there is also damage that we cannot see so well, the damage below the waterline of our democracy – damage caused, I believe, by a systematic effort to twist policy to suit political ends; to substitute ideology for science, fact, and law; and to misuse instruments of power.

If an administration rigged the intelligence process and on faulty intelligence sent our country to war;

If an administration descended to interrogation techniques of the Inquisition, of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge – descended to techniques that we have prosecuted as crimes in military tribunals and in federal courts;

If institutions as noble as the Department of Justice and as vital as the Environmental Protection Agency were subverted by their own leaders;

If the integrity of our markets and the fiscal security of our budget were opened wide to the frenzied greed of corporations, and speculators and contractors;

If taxpayers were cheated, and the forces of government rode to the rescue of the cheaters and punished the whistleblowers;

If our government turned the guns of official secrecy against our own people to mislead, confuse and propagandize them;

If the integrity of public officials; the warnings of science; the honesty of government procedures; and the careful historic balance of our separated powers, all were seen as obstacles to be overcome and not attributes to be celebrated;

If the purpose of government became no longer to solve problems, but simply to work them for political advantage, and a bodyguard of lies, jargon, and propaganda were emitted to fool and beguile the American people…

Well, something very serious would have gone wrong in our country – and such damage must be repaired. I submit that as we begin the task of rebuilding this nation, we have a duty to our country to determine how great that damage is.

Democracy is not a static institution, it is a living education – an ongoing education in freedom of a people. As Harry Truman said addressing a joint session of Congress back in 1947, “One of the chief virtues of a democracy is that its defects are always visible, and under democratic processes can be pointed out and corrected.” We have to learn the lessons from this past carnival of folly, greed, lies, and wrongdoing, so that the damage can, under democratic processes, be pointed out and corrected.

If we blind ourselves to this history, we deny ourselves its lessons – lessons that came at too painful a cost to ignore. Those lessons merit disclosure and discussion. Indeed, disclosure and discussion make the difference between this history being a valuable lesson for the bright and upward forces of our democracy, or a blueprint for those darker forces to return and someday do it all over again.

As we work toward a brighter future ahead, to days when jobs return to our cities, capital to our businesses, and security to our lives, we cannot set aside our responsibility to take an accounting of where we are, what was done, and what must now be repaired.

We also have to brace ourselves for the realistic possibility that as some of this conduct is exposed, we and the world will find it shameful, revolting. We may have to face the prospect of looking with horror at our own country’s deeds. We are optimists, we Americans; we are proud of our country. Contrition comes hard to us.

But the path back from the dark side may lead us down some unfamiliar valleys of remorse and repugnance before we can return to the light. We may have to face our fellow Americans saying to us, “No, please, tell us that we did not do that, tell us that Americans did not do that” – and we will have to explain, somehow. This is no small thing, and not easy; this will not be comfortable or proud; but somehow it must be done.

Chairman Leahy has embarked on the process of considering a new commission; one appropriate to the task of investigating the damage the Bush Administration did to America, to her finest traditions and institutions, to her reputation and integrity. The hearing he’s called in coming days will more thoroughly examine this question, to help us determine how best to move forward. I stand with him. Before we can repair the harm of the last eight years, we must learn the truth.

I thank the presiding officer and I yield the floor.

Sen. Pat Leahy, on the Senate floor, today:

As Prepared

When historians look back at the last eight years, they will evaluate one of the most secretive administrations in the history of the United States. Last November, the American people made clear their desire for change. I share that desire to move forward, and to reestablish ourselves as a Nation dedicated to the rule of law, respected and trusted throughout the world.

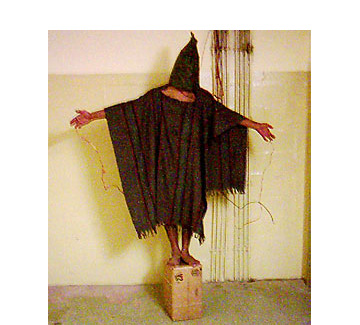

We also know that the past can be prologue unless we set things right. The last administration justified torture, presided over the abuses at Abu Ghraib, destroyed tapes of harsh interrogations, and conducted “extraordinary renditions” that sent people to countries that permit torture during interrogations. The last administration used the Justice Department – our premier law enforcement agency – to subvert the intent of congressional statutes. They wrote secret law to give themselves legal cover for these misguided policies, policies that could not withstand scrutiny if brought to light.

Nothing has done more to damage America’s standing and moral authority than the revelations that, during the last eight years, we abandoned our historic commitment to human rights by repeatedly stretching the law and the bounds of executive power to authorize torture and cruel treatment. As President Obama said to Congress and to the American people last night, “…if we’re honest with ourselves, we’ll admit that for too long we have not always met” our responsibilities. But what the President said about the economy also holds true here, “it is only by understanding how we arrived at this moment” that we will be able to move forward. How can we restore our moral leadership and ensure transparent government if we ignore what has happened?

There has been discussion, and in some cases disagreement, on how best to do this. There are some who resist any effort to investigate the misdeeds of the recent past. Indeed, some Republican Senators tried to extract a devil’s bargain from Attorney General Holder – a commitment that he would not prosecute for anything that happened on President Bush’s watch. That is a pledge no prosecutor should give, and Eric Holder did not.

There are others who say that, regardless of the cost in time, resources, and unity, we must prosecute Bush administration officials to lay down a marker. The courts are already considering congressional subpoenas that have been issued and claims of privilege and legal immunities – and they will be for some time.

Over my objection, Congress has already passed laws granting immunity to those who facilitated warrantless wiretaps and conducted cruel interrogations. The Department of Justice issued legal opinions justifying these executive branch excesses which, while legally faulty, would undermine attempts to prosecute. A failed attempt to prosecute for this conduct might be the worst result of all if it is seen as justifying abhorrent actions. Given the steps Congress and the executive have already taken to shield this conduct from accountability, that is a possible outcome.

The alternative to these approaches is a middle ground, a middle ground I spoke of at Georgetown University a little over two weeks ago. That middle ground would involve the formation of a commission of inquiry dedicated to finding out what happened. Such a commission’s objective would be to find the truth. People would be invited to come forward and share their knowledge and experiences, not for the purpose of constructing criminal indictments, but to assemble the facts, to know what happened and to make sure mistakes are not repeated.

While many are focused on whether crimes were committed, it is just as important to learn if significant mistakes were made, regardless of whether they can be proven beyond a reasonable doubt to a unanimous jury to be criminal conduct. We compound the serious mistakes already made if we limit our inquiry to criminal investigations and trials. Moreover, it is easier for prosecutors to net those far down the ladder than those at the top who set the tone and the policies. We do not yet know the full extent of our government’s actions in these areas, and we must be sure that an independent review goes beyond the question of whether crimes were committed, to the equally important assessment of whether mistakes were made so we may endeavor not to repeat them. As I have said, we must read the page before we turn it.

Vice President Dick Cheney continues to assert unilaterally that the Bush administration’s tactics, including torture, were appropriate and effective. But interested parties’ characterizations and self-serving conclusions are not facts and are not the unadulterated truth. We cannot let those be the only voices heard, nor allow their declarations to serve as historical conclusions on such important questions. An independent commission can undertake this broader and fundamental task.

I am talking about this process with others in Congress, with outside groups and experts, and I have begun to discuss this with the White House as well. I am not interested in a commission of inquiry comprised of partisans, intent on advancing partisan conclusions. Rather, we need an independent inquiry that is beyond reproach and outside of partisan politics to pursue and find the truth. Such a commission would focus primarily on the subjects of national security and executive power in the government’s counterterrorism effort. We have had successful oversight in some areas, but on these issues, including harsh interrogation tactics, extraordinary rendition and executive override of the laws, the last administration successfully kept many of us in the dark about what happened and why.

President Obama issued significant executive orders in his first days in office, looking to close Guantanamo and secret prisons, banning the use of harsh interrogation techniques and forming task forces to review our detainee and interrogation policies. I support his decisions, and I am greatly encouraged by his determination to do the hard work to determine how we can reform policies in these areas to be lawful, effective and consistent with American values. My proposal for a commission of inquiry would address the rest of the picture, which is to understand how these types of policies were formed and exercised in the last Administration, to ensure that mistakes are not repeated. I am open to good ideas from all sides as to the best way to set up such a commission and to define its scope and goals.

A recent Gallup poll showed that 62 percent of Americans favor an investigation of these very issues. Respected groups including Human Rights First, the Constitution Project and thoughtful Senators including Senator Whitehouse and Senator Feingold have also embraced this idea. The determination to look beyond the veil that has so carefully concealed the decision making in these areas is growing. Next Wednesday, the Judiciary Committee will hold a hearing to explore these ideas, and to continue the conversation about what we can do moving forward.

Two years ago I described the scandals at the Bush-Cheney-Gonzales Justice Department as the worst since Watergate. They were. We are still digging out from the debris they left behind while those in the last administration continue to defend their policies, knowing full well that we do not even know the full extent of what those polices were or how they were made. We cannot be afraid to understand what we have done if we are to remain a Nation equally vigilant in defending both our national security and our Constitution. I hope all members of Congress will give serious consideration to these difficult questions.