Whenever a Democratic president takes office, hopes arise for a more rational approach to our relationship with Cuba, object of an embargo that has lasted for nearly half a century without improving the behavior of that country's authoritarian leaders. Such hopes are encouraged by the Obama administration, which has signaled its intention to lift restrictions on travel to the island and cash remittances to family members by Cuban-Americans and -- as members of the Organization of American States prepare for their upcoming summit in Trinidad -- offered a few tantalizing hints that this tentative new opening is merely a beginning.

Ambassador Jeffrey Davidow, the president's principal adviser in preparing for Trinidad, recently said that he "would not be surprised" if the White House announced the new regulations before the summit opens. He noted that the president is considering Congressional proposals for further opening to the island, may well appoint a special envoy to promote engagement, and could conceivably end U.S. opposition to Cuban membership in the OAS. "We are engaged in a continual evaluation of our policy and how that policy could help result in a change in Cuba that could bring about a democratic society," Davidow said.

Aside from Davidow's remarks, the most suggestive sign of a new approach to Cuba came last week when federal prosecutors announced a new indictment of Luis Posada Carriles, the notorious exile militant who has long boasted of his role in terror bombings aimed at overturning the Castro regime. The indictment handed up by a grand jury in El Paso, Texas, accused him of deceiving immigration authorities about his role in several terrorist attacks on tourist destinations in Cuba in 1997. Praised by the Cuban government, the new charges against Posada Carriles marked a sharp departure from the coddling he enjoyed when the Bush administration ran the Justice Department.

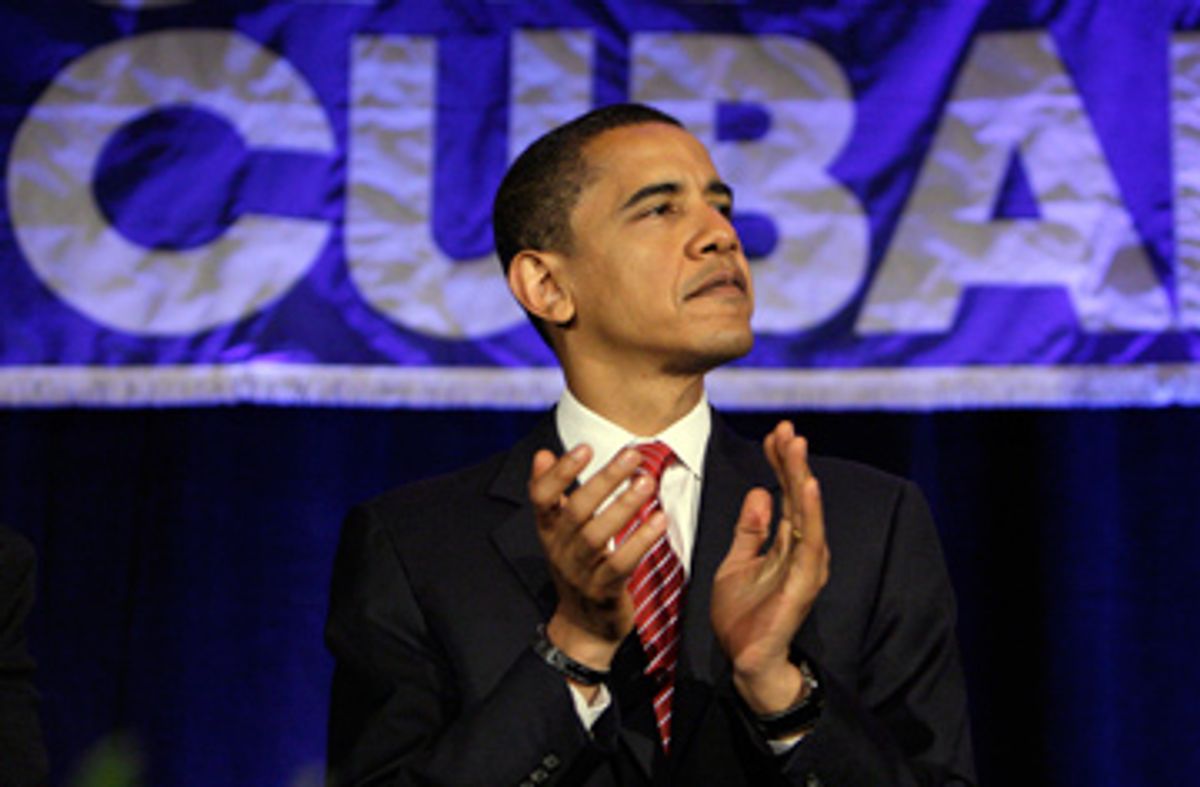

Relaxing the restrictions imposed by the Bush administration would fulfill a campaign promise by President Barack Obama, whose own policy toward Cuba has changed over time. When he ran for the Senate five years ago, he bluntly favored ending the embargo; as a presidential candidate, he dropped that position and assured Cuban-Americans that he would maintain the embargo while engaging in direct diplomacy with the Cuban government.

While Obama's shifting position provoked angry blasts from the Republican right and its traditional allies in the exile community during the campaign, he understood that American views of Cuba have been changing gradually for at least a decade, across partisan lines and even in the second and third generations of Cuban-Americans. The question he must eventually face is whether to pursue the logic of his own policy of engagement, leading to the eventual normalization of relations and lifting of the embargo.

Indeed, he will have to formulate at least a preliminary answer when he meets for the first time with the other members of the OAS, all of which maintain normal (and in several cases quite close) relations with Cuba. Meanwhile, pressure for further liberalization of rules governing U.S. travel and trade is building in the Senate and Congress, with bills to allow all Americans to visit the island and permitting easier commerce have gathered hundreds of bipartisan sponsors.

Opponents of improved relations with Cuba insist that every dollar spent or invested there merely strengthens the government of Raul Castro, the brother of Fidel. They point to the repression and deprivation suffered by the Cuban people, and especially the political prisoners who have languished in the regime's prisons for years. But as Obama appears to understand, advocates of the embargo have no substantive plan to promote change on the island. He also knows that the failed attempt to isolate Cuba has only succeeded in alienating the United States from the rest of the hemisphere at a time when his ambitious agenda on climate change and development needs all the support he can muster.

Sooner or later, Obama will have to choose between the middling position he has adopted so far and the additional steps that must be taken to foster real change. There is no real excuse for permitting Cuban-Americans to travel to the island while forbidding other Americans to go there -- particularly when the U.S. government imposes no restrictions on travel to Iran, for instance.

But more important is the fundamental truth that has been ignored by the embargo's supporters for more than two decades -- namely that the idea of isolating one small island, supposedly over human rights violations, directly conflicts with American policy toward regimes that oppress millions more people. Without minimizing any of the complaints against the Castro regime, it is worth noting the relative scale and nature of its offenses compared with those of other governments.

The monitors at Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International estimate that the Cuban government currently holds some 60 political prisoners. Those same monitors say that the Chinese government is holding hundreds and perhaps thousands of political prisoners in the wake of recent protests in Tibet; nobody knows for certain because Beijing declines to answer any inquiries about those detainees. That is merely business as usual in China, where torture, arbitrary arrest, and capital punishment are routine instruments of repression, turned against anyone deemed a threat to the government. In Saudi Arabia, similar forms of repression, including public executions and flogging, are inflicted on critics of the ruling elite, whose extreme religious intolerance makes Cuba seem liberal. In Vietnam, a former enemy with which we normalized relations at the urging of John McCain, regime critics are still treated much the same as in Cuba.

The hope cherished by policymakers of both parties is that in all those places, cultural, diplomatic, commercial and political engagement will create openings that would not exist otherwise -- and there is evidence to support that long view, despite news that is often discouraging. What there is no evidence to support is the idea that the embargo on Cuba has any effect whatsoever, except to worsen the lives of ordinary Cubans. It is intellectually and politically dead. Let's hope Obama has the courage to bury it.

Shares