What’s the administration’s specific aim in bailing out G.M.? I’ll give you my theory later.

For now, though, some background. First and most broadly, it doesn’t make sense for America to try to maintain or enlarge manufacturing as a portion of the economy. Even if the U.S. were to seal its borders and bar any manufactured goods from coming in from abroad — something I don’t recommend — we’d still be losing manufacturing jobs. That’s mainly because of technology.

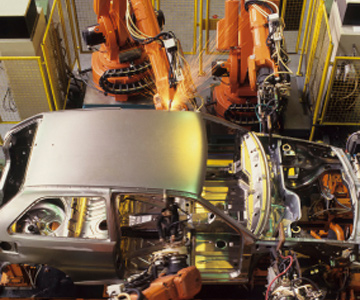

When we think of manufacturing jobs, we tend to imagine old-time assembly lines populated by millions of blue-collar workers who had well-paying jobs with good benefits. But that picture no longer describes most manufacturing. I recently toured a U.S. factory containing two employees and 400 computerized robots. The two live people sat in front of computer screens and instructed the robots. In a few years this factory won’t have a single employee on site, except for an occasional visiting technician who repairs and upgrades the robots.

Factory jobs are vanishing all over the world. Even China is losing them. The Chinese are doing more manufacturing than ever, but they’re also becoming far more efficient at it. They’ve shuttered most of the old state-run factories. Their new factories are chock full of automated and computerized machines. As a result, they don’t need as many manufacturing workers as before.

Economists at Alliance Capital Management took a look at employment trends in 20 large economies and found that between 1995 and 2002 — before the asset bubble and subsequent bust — 22 million manufacturing jobs disappeared. The United States wasn’t even the biggest loser. We lost about 11 percent of our manufacturing jobs in that period, but the Japanese lost 16 percent of theirs. Even developing nations lost factory jobs: Brazil suffered a 20 percent decline, and China had a 15 percent drop.

What happened to manufacturing? In two words, higher productivity. As productivity rises, employment falls because fewer people are needed. In this, manufacturing is following the same trend as agriculture. A century ago, almost 30 percent of adult Americans worked on a farm. Nowadays, fewer than 5 percent do. That doesn’t mean the U.S. failed at agriculture. Quite the opposite. American agriculture is a huge success story. America can generate far larger crops than a century ago with far fewer people. New technologies, more efficient machines, new methods of fertilizing, better systems of crop rotation, and efficiencies of large scale have all made farming much more productive.

Manufacturing is analogous. In America and elsewhere around the world, it’s a success. Since 1995, even as manufacturing employment has dropped around the world, global industrial output has risen more than 30 percent.

We should stop pining after the days when millions of Americans stood along assembly lines and continuously bolted, fit, soldered or clamped what went by. Those days are over. And stop blaming poor nations whose workers get very low wages. Of course their wages are low; these nations are poor. They can become more prosperous only by exporting to rich nations. When America blocks their exports by erecting tariffs and subsidizing our domestic industries, we prevent them from doing better. Helping poorer nations become more prosperous is not only in the interest of humanity but also wise because it lessens global instability.

Want to blame something? Blame new knowledge. Knowledge created the electronic gadgets and software that can now do almost any routine task. This goes well beyond the factory floor. America also used to have lots of elevator operators, telephone operators, bank tellers and service-station attendants. Remember? Most have been replaced by technology. Supermarket check-out clerks are being replaced by automatic scanners. The Internet has taken over the routine tasks of travel agents, real estate brokers, stockbrokers and even accountants. With digitization and high-speed data networks a lot of back office work can now be done more cheaply abroad.

Any job that’s even slightly routine is disappearing from the U.S. But this doesn’t mean we are left with fewer jobs. It means only that we have fewer routine jobs, including traditional manufacturing. When the U.S. economy gets back on track, many routine jobs won’t be returning — but new jobs will take their place. A quarter of all Americans now work in jobs that weren’t listed in the Census Bureau’s occupation codes in 1967. Technophobes, neo-Luddites and anti-globalists be warned: You’re on the wrong side of history. You see only the loss of old jobs. You’re overlooking all the new ones.

The reason they’re so easy to overlook is that so much of the new value added is invisible. A growing percent of every consumer dollar goes to people who analyze, manipulate, innovate and create. These people are responsible for research and development, design and engineering. Or for high-level sales, marketing and advertising. They’re composers, writers and producers. They’re lawyers, journalists, doctors and management consultants. I call this “symbolic analytic” work because most of it has to do with analyzing, manipulating and communicating through numbers, shapes, words, ideas.

Symbolic-analytic work can’t be directly touched or held in your hands, as goods that come out of factories can be. In fact, many of these tasks are officially classified as services rather than manufacturing. Yet almost whatever consumers buy these days, they’re paying more for these sorts of tasks than for the physical material or its assemblage. On the back of every iPod is the notice “Designed by Apple in California, Assembled in China.” You can bet iPod’s design garners a bigger share of the iPod’s purchase price than its assembly.

The biggest challenge we face over the long term — beyond the current depression — isn’t how to bring manufacturing back. It’s how to improve the earnings of America’s expanding army of low-wage workers who are doing personal service jobs in hotels, hospitals, big-box retail stores, restaurant chains, and all the other businesses that need bodies but not high skills. More on that to come.