My eldest daughter had a rough first week. Born after 22 hours of hard labor, her pink skin proceeded to turn an alarming shade of yellow on the second day of her life. It was a bad case of jaundice. She would need to be placed in an incubator, whose ultraviolet light would hopefully clear up the condition. If not, a transfusion would be required. My exhausted wife and I watched in numb horror as our child was encased in the clear plastic box that was to become her crib for the next seven days. What we had hoped would be a straightforward delivery had turned into a nightmare.

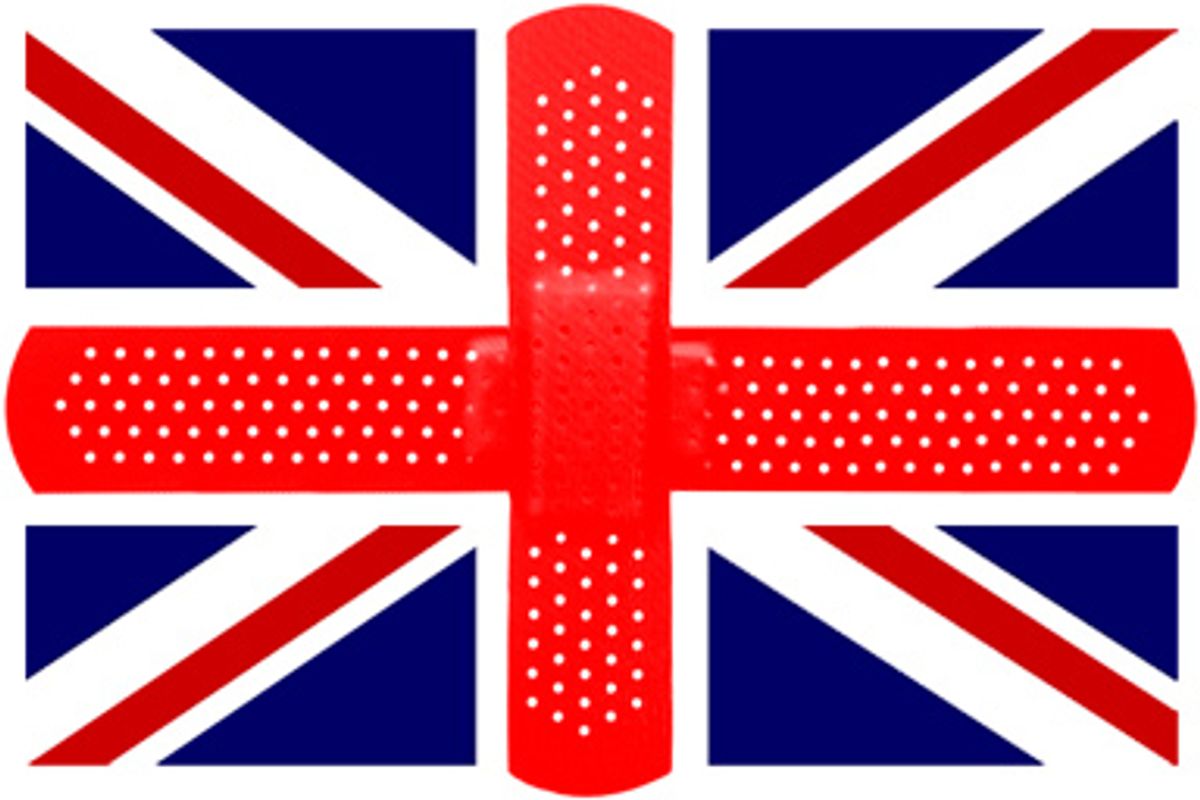

Because I am American, and those endless days and nights were spent in a maternity hospital in London, the week that followed has been very much on my mind as I listen to the recent attacks on the British National Health Service. It is a system that I found to be very different from the one currently being described as "evil" and "Orwellian" by politicians and commentators eager to use it as an example of the dark side of public medicine.

I was initially skeptical about the NHS. I’d grown up comfortably in suburban New Jersey; good private healthcare was always immediately available through my father’s insurance. When my English wife became pregnant soon after we settled in London, I was alarmed by the idea of having our first child born in a system I had been told was underfunded, overstressed and inefficient. After all, healthcare in the UK was free. How good could it be? Friends and relatives back in the States were spending thousands to have children. If you get what you pay for, I was about to get a whole lot of nothing.

My first glimpse of our prospective hospital was not promising. It seemed crowded, aging and apparently devoid of the gleaming, beeping equipment I associated with modern medicine. But our neo-natal class actually helped me prepare for the upcoming birth, and the scans we received afforded the same miraculous fetal glimpses we would have gotten back in New Jersey. Come delivery day, an impressive team of midwives, nurses and anesthesiologists attended my wife’s long labor, all of them respecting her request not to opt for a cesarean section. When things got sticky at the end, a senior obstetrician appeared and the monitoring equipment beeped reassuringly.

Directly following the birth, we were taken to a large ward whose 20-odd beds were separated by curtains and changing tables. It was visiting hour; the place was alive with excited relatives, shellshocked fathers and the constant susurrus of hungry new life. That first night, however, the atmosphere grew peaceful. Crying babies were attended immediately by sensibly-shod nurses so that others could sleep. But it was after my daughter began to turn the color of saffron rice that I really began to appreciate the NHS. The moment she showed distress, we were whisked off to a private room, where we were looked after by a no-nonsense pediatrician and the imposing Irish ward sister, or chief nurse, who quickly made it clear to me that my sole useful contribution to the whole process had come nine months earlier. Blood was drawn regularly from our daughter’s tiny heel; test results came back promptly. The meals were surprisingly edible. I even developed a taste for the milky tea brought to me by kind nurses. My only complaints over the following week were that the free cookies in the father’s lounge were always running out. And for some reason the ward sister kept giving me withering looks, no matter how dutifully I attended to my family’s needs.

As my blindfolded daughter slept in the incubator’s eerie violet glow, I would take occasional strolls through the ward. It was the most egalitarian place I had ever seen. The yuppie woman honking into her newfangled cell phone, the young Pakistani mother who always seemed to be surrounded by a half-dozen gift-bearing relations, the self-sufficient older woman desperate to get home to look after her other children -- all of them were cared for in exactly the same manner. Whoever needed help got it. When a terrified Afghani girl arrived, rumored to be only 14 and apparently abandoned by her family, several nurses dropped what they were doing to teach her the rudiments of child care. The rest of the mothers waited patiently until they were finished. Other wards were the same. There was no private wing with champagne service. Everybody was in this together. If you were a woman and you were in labor and you were in our part of London, this is where you came. If things went wrong, skilled doctors appeared with the latest technology. Nobody asked about insurance or co-pays.

This, I learned, is what the NHS is about -- common decency. It is about the shared belief that all the people who live in the United Kingdom constitute a society, and a decent society provides certain necessities for its members. Freedom from hunger is one. Police protection is another. Free healthcare from the cradle to the grave is simply one more item on this list.

I saw this decency at work countless times over the following decade, until my return to the United States. I saw it with the twice-daily home visits by community midwives for the fortnight after each of our newborn children’s release from hospital, and in the vouchers for free milk we were given for those babies. I saw it when our GP paid us a house call early one Sunday morning to treat our son’s spiking fever.

I saw it most clearly, however, in the treatment my in-laws received at the end of their lives. My wife’s father, who suffered from acute myloid dysplasia, spent his last year receiving constant care, including several sprints to the hospital for emergency transfusions, where doctors struggled heroically to keep him alive. His final week was spent in a very comfortable single hospice room whose French doors opened onto a terrace overlooking his beloved Yorkshire moors. When he died, he left us his house, and not a penny of healthcare debt. My mother-in-law, stricken by arthritis, got two artificial hips and two knees from the NHS, and received daily home visits from social workers during the last three years of her life so she would not have to go into a nursing home. Neither of these septuagenarians was working at the time. The amount of money spent on their care must have been staggering. And yet, despite shouldering this yoke of decency, the nation prospered around them. People were buying French wine and German cars and second homes. They were attending Cats and supporting Arsenal and going on holidays in the sun. Sure, people complained about the NHS. But the British complain about everything. Living without a public health system, on the other hand, was unthinkable.

On the day we were finally given the all-clear, there were no papers to sign, no bills to settle. All we had to do was remove our daughter’s blindfold and go. But I felt I had to leave something behind. So I rushed down to the local corner shop and bought several tins of cookies to give the staff who’d looked after us so well. As luck would have it, the Irish ward sister was the only one at the nurse’s station when I arrived. Before I could explain myself, she gave me a tight, approving smile.

"Wondered when you’d start chipping in," she said, returning to her paperwork. "Just leave them in the father’s lounge."

Shares