The surgery complete, the great doctor finally stepped back from the operating table and paused for a moment of self-congratulation.

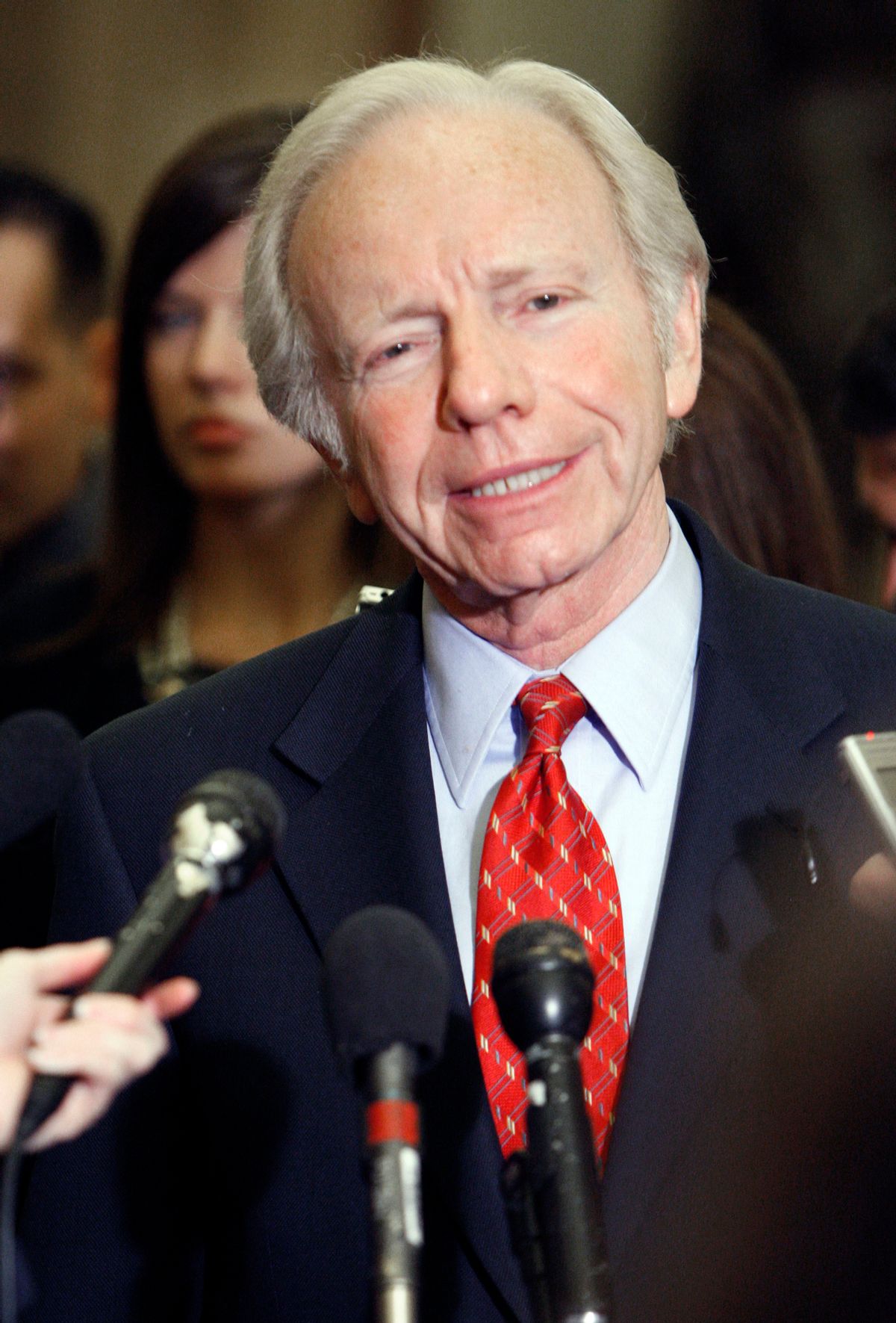

"We've got a great health insurance reform bill here," Sen. Joe Lieberman, I-Conn., told reporters solemnly Tuesday morning, after he had forced Democrats to jerk the bill to the right yet again to buy his vote on President Obama's top domestic policy priority. "And the danger was that some of my colleagues, I think, were just trying to load it up with too much. And what happens then is that you run the risk of losing everything." Lieberman doesn't use a scalpel when he's operating on legislation, of course; he goes for brute force instead. So what if he'd bludgeoned the patient half to death in the course of the procedure?

By the time Lieberman was done with his intervention into the healthcare reform process Tuesday, two things were clear. One, it only looked like the Democrats controlled the Senate by a filibuster-proof margin. The party that's actually running the show is an obscure, regional outfit known as the Connecticut for Lieberman Party. And the guy who was elected on its ticket -- a hack who worked his way up the ranks by showing undying devotion to the party's cause, i.e., advancing the political career of its founder -- isn't really on board for all the hope and change of 2008.

And two, the end stages of the debate over healthcare reform will essentially be a mad scramble by progressives to mitigate the damage Lieberman and conservative Democrats can do to the legislation before it passes -- and to try to convince their wavering allies that the bill is still worth supporting. What started out as a sweeping effort to change the entire healthcare system looks likely to wind up as a moderately ambitious attempt to regulate the insurance market (in exchange for a promise of millions of new customers).

"We're not going to get all that we want," said Sen. Jay Rockefeller, D-W.Va., a leading advocate for the now-defunct public option. "But we're going to get so much more than we have." Rockefeller and most of his colleagues were singing from the same rueful hymnal. "Look at 31 million Americans who will have health insurance as a result of this bill," said Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., the second-ranking Senate Democrat. "How do you say to them, 'Sorry, you can't have health insurance, we think this bill could be better'? ... I'm not happy with it, I don't like the way this has happened. But at this point in time, look at where we are."

If that sounds a little like rationalization, it probably is: Chances are progressives won't be able to shift the bill back to the left much, even in a conference between the House and Senate. Keeping Lieberman on board is simply the price of doing business. Trying to pass parts of the legislation through budget reconciliation, which many liberals see as a magic bullet, might just be a fantasy. The rules of that process would mean most of the insurance reforms in the legislation get dropped. So that means Democrats need 60 votes -- and that puts Lieberman, and Nebraska Sen. Ben Nelson, another conservative who has refused to endorse the bill yet, in a position to exact a heavy price.

Which they've certainly done. They managed to kill not just the notion of a public health insurance option, but also the compromise Democrats had hatched just a week ago, which would have expanded Medicare a bit instead of launching a government-run insurance plan. That's not the end of the damage. To get the bill through the Senate, Democrats will probably have to fund its $900 billion price tag by taxing expensive health benefits packages, instead of with a new tax on the rich, as the House prefers. Some sort of language restricting access to abortion under the new, government-supervised insurance exchanges will be thrown in, as a sop to win Nelson's anti-choice favor. Access to Medicaid, the government insurance program for the poor, won't be expanded as much as many progressives want. And yes, the bill would dole out $50 million to groups teaching abstinence-only sex education plans, which helped buy the support of Sen. Blanche Lincoln, D-Ark.

All that seems like too much to swallow for many liberals. "Honestly, the best thing to do right now is kill the Senate bill," former Democratic National Committee Chairman Howard Dean told Vermont Public Radio. "The Senate has somehow managed to turn the House's silk purse into a sow's ear," said Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Ariz., co-chairman of the House Progressive Caucus. "Without a public option and no hope of expanding Medicare coverage, this bill is not worth supporting," said Stephanie Taylor, the co-founder of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee. Liberal blogs erupted with anger, and Taylor's group released a video targeting White House chief of staff Rahm Emanuel, who many on the left think has manipulated the process in order to crush progressives' dreams.

But President Obama and Senate Democrats tried, even in the face of all that outrage, to remind their erstwhile allies of what else the bill does. "The final bill won't include everything that everybody wants," Obama said after meeting with Senate Democrats -- including Lieberman -- at the White House. "No bill can do that. But what I told my former colleagues today is that we simply cannot allow differences over individual elements of this plan to prevent us from meeting our responsibility to solve a long-standing and urgent problem for the American people. They are waiting for us to act."

The legislation would, after all, bar insurance companies from refusing coverage to people who are already sick. It would give federal subsidies to people who can't afford insurance coverage on their own. It would set up a regulated marketplace to shop for policies. It would set up some experiments in changing the way medical care is paid for, to reward outcomes instead of procedures, which could save the country billions of dollars down the line. It would at least alleviate, if not completely fix, the status quo, which left untouched would lead to continuing, rapid increases in premium costs for the middle class -- and continue the insurance industry's capricious practice of denying care just when it's most needed. Yes, the insurance companies would get millions of new customers, thanks to a new federal requirement that all individuals buy insurance. But is the point of reform to punish the insurers, or is it to expand access to what every other industrialized nation considers a basic human right?

It wasn't hard to see where the White House came down on that question. "These aren't small changes," Obama said. "These are big changes. They represent the most significant reform of our healthcare system since the passage of Medicare. They will save money. They will save families money; they will save businesses money; and they will save government money. And they're going to save lives." Joe Lieberman may have won the battle Tuesday. But the White House is determined to win the war.

Shares