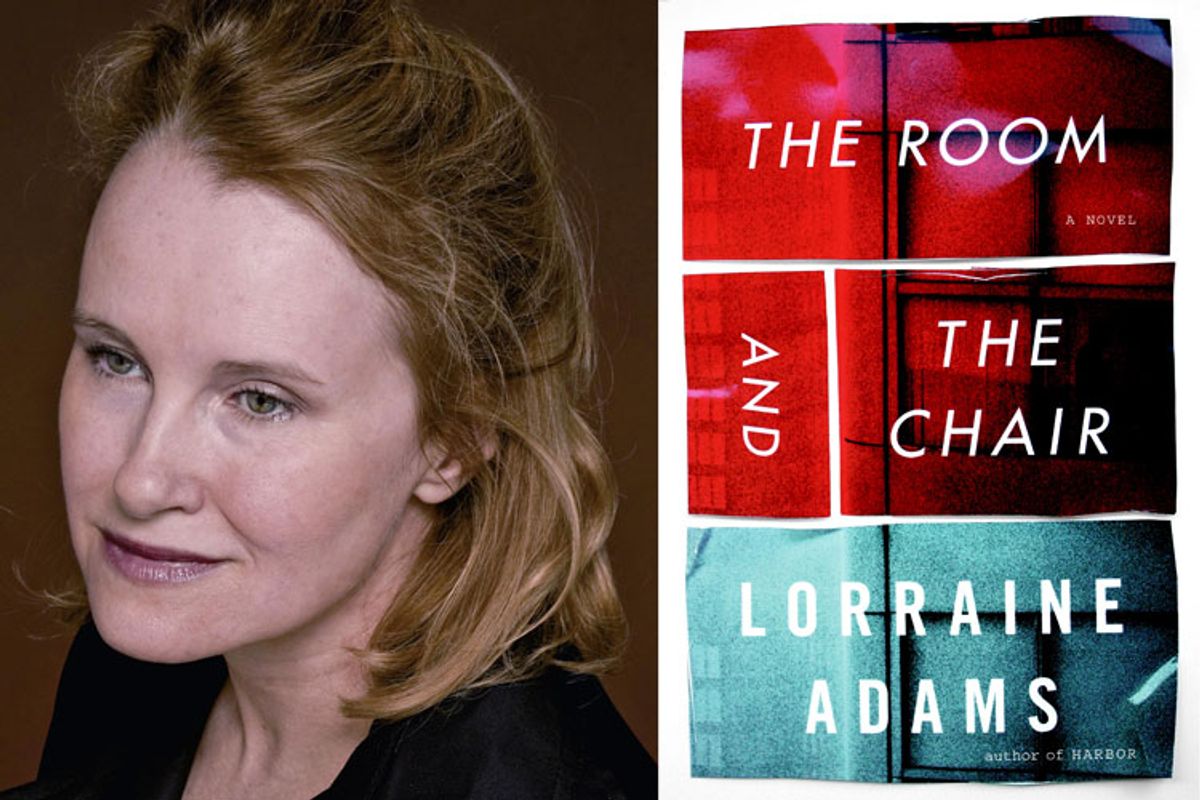

At the start of Lorraine Adams' new novel, "The Room and the Chair," a mysterious F-16 fighter jet crashes into the Potomac River, causing an explosion heard by guests of the Watergate Hotel. Within minutes, the media has interpreted the event in half a dozen ways. And for the remainder of the book, high-ranking White House officials, with the press's cooperation, will spin it until it blurs, implicating everyone from special operatives in Afghanistan to a teenage prostitute who witnessed the crash.

Adams' follow-up to her 2005 novel, "Harbor," reads like a season of "The Wire." Only here the Washington Spectator (a thinly veiled Washington Post) has replaced the Baltimore Sun, and the streets of Hormuz, in the Persian Gulf, stand in for the projects. Written in a precise, lyrical voice, the book takes place shortly after 9/11 and provides an inside view of both the U.S. intelligence community and the newsroom floor, allowing Adams to explore how reality is created, warped and disguised at the whims of those in power.

Adams' depictions of journalistic hierarchies are especially vivid, as you would expect from a Pulitzer-winning writer who spent 11 years as a reporter for the Washington Post. There's Adam Sanger, the executive editor, whose thirst for fresh news overrides his interest in historical truth. Beneath him is Stanley Belson, the sensitive, beleaguered night editor, weary of seeing the galaxies of human nature shoehorned into a few predictable storylines. And at the bottom is Vera Hastings, the newbie beat reporter and former ballerina, whose passion and ambition are almost comically thwarted at every turn.

Adams recently spoke with Salon over the phone from her apartment in New York City about the death of journalism, why she'll never again write nonfiction, and the massive egos of White House reporters.

You began writing your first novel right after 9/11. Months before that, you'd left the Washington Post newsroom to become a contract writer for the paper. What sort of changes did you notice in the way the news was reported after 9/11?

In the immediate aftermath, the first year, there was a feeling of patriotism that made it difficult to report fairly. The Post says, "We don't report objectively, we report fairly." And I would argue that in any country that's been attacked, the reporters are not going to be able to be fair. If you read the history of war reporting, you can see it, even in the best people. Ernie Pyle's accounts from North Africa are gorgeous pieces of reportage, but they're very pro-American. So I noticed that change. I'm not saying it's wrong. I think it's impossible to be fair in those situations.

You worked as a news journalist, first at the Dallas Morning News, then at the Post for over a decade. Why did you decide to write a novel?

After 20 years of reporting and writing news stories, I was well acquainted with what many call a jaded perspective, or what I call a wised-up perspective. I realized that I could probably find out what happened in many different ways, I just couldn't put it in the newspaper, and there would always be something I couldn't get at because I announced myself as a reporter. That frustration built. By the end, the frustration was so unbearable that novel writing seemed to me the only way to approximate a better truth.

So you'll never go back to writing nonfiction?

I'll never write nonfiction again. I've thought about it, and talked about it with my agent. I was thinking of writing about the Bam earthquake in Iran a while ago. But there were always difficulties. One, for example, was that the people I wanted to talk to -- about the horrific things that happened because of the ineptitude of the Iranian regime -- these people were afraid to talk to American journalists because that could mean a term in Evin prison. I'm not willing to make people talk to me and risk their facing solitary confinement as a result. I think it's unconscionable.

How do you feel about the ways blogs and alternative news sources have changed the way news is reported and consumed?

In the news business, there's always been a sense of hierarchies of authoritativeness, that a story isn't real until CNN or whoever reports it. I think that's going to change. I think we'll stop privileging news outlets. Especially considering what's been going on lately. When you've got a book on Hiroshima, for example, published by Henry Holt, and you find out that the writer wasn't just duped by one pilot, but there's a whole slew of things that are wrong and they're withdrawing the book. The privileging of the content platform gets called into question. That's what happened with James Frey and Oprah. These privileged outlets aren't checking anything either. So why should they be accorded a certain reverence in terms of truthfulness?

You once said in an interview that the forms of storytelling haven't really changed since the New Journalism era of the '60s. Why do you think so little has changed, especially in newspapers and magazines?

Right now they're in a siege mentality. And when you're in a siege mentality, you hunker down and you do what's tried and true. Although, at this point, it's contributing to their downfall and their lack of readers, but they somehow seem blind to that and I can't see why. As for the New Journalism guys, they were reinventing a form and making journalism into this thing we now call reportage, the kind of stuff in the New Yorker and Granta, which are now dying. In a daily newspaper, they don't want you to write like that. But they think they do!

I remember once writing a magazine article for the Washington Post, and I used the word "refrigerant." And the editors were like, "This is too fucking showy, this is pretentious, fuck you." I had to go to John McPhee's book about Alaska, "Coming Into the Country," and point out that he used the word "refrigerant," and then they let me use it.

In his new book, "Reality Hunger: A Manifesto," David Shields argues that the novel is not as relevant as it once was. Do you think this is true?

Of course it's fashionable to say the novel is irrelevant to the culture or it's dead. And yet the novel miraculously persists. I remember one of the first books I reviewed was a biography of Fanny Burney, a novelist and playwright around the turn of the 19th century. Her father and her brother were both well-known historians. But Burney, for whatever reason, is the one that survived. We don't read those historians at all. You can't say that essays survive the way novels do. Maybe Sam Johnson, but that's fucking rare.

There's Montaigne. And Emerson.

Yeah, we got three there. But I think there are a fuck of a lot more novels that survive, and I don't think the human condition has so radically changed that that won't be the case. I believe that art endures, and I don't believe that commentary does.

Vera Hastings, the young night-cop reporter in the novel, is told by her college guidance counselor that journalism is dead, and yet she goes into it anyway. Did anyone try to dissuade you from a journalism career?

Coming out of graduate school at Columbia, David Remnick was a dear friend. And when I told him I planned to go into journalism, which he was already doing, he said, "No no no, don't go into newspapers. It's all over. You should go into cable television, that's where the future lies." Well, cable TV news today is frantic, crazed, losing audiences.

I would argue: Go where you cannot help but go. Go where you just can't stop yourself from going. All the advice in the world amounts to nothing if you don't have passion for the work.

Much of your new novel has to do with the ways reality is created and warped, not just by the players in Washington, but by the reporters and editors that cover them. Are White House reporters really that megalomaniacal?

Most definitely. Journalists who are considered at the top of their games are assigned to the White House. People like Judith Miller -- who was talking to Scooter Libby, Cheney's chief of staff -- was aligning herself with these men and saying, "I'm as big a deal as they are, I'm one of the actors, not one of the observers." The egos of some of these writers is such that they come to identify with the people they write about. They want to feel that they are as big as their subjects.

What we really need is not more information about the people in power. We need more information about the ways in which decisions are informed by the facts, and how those facts come to be facts.

Shares