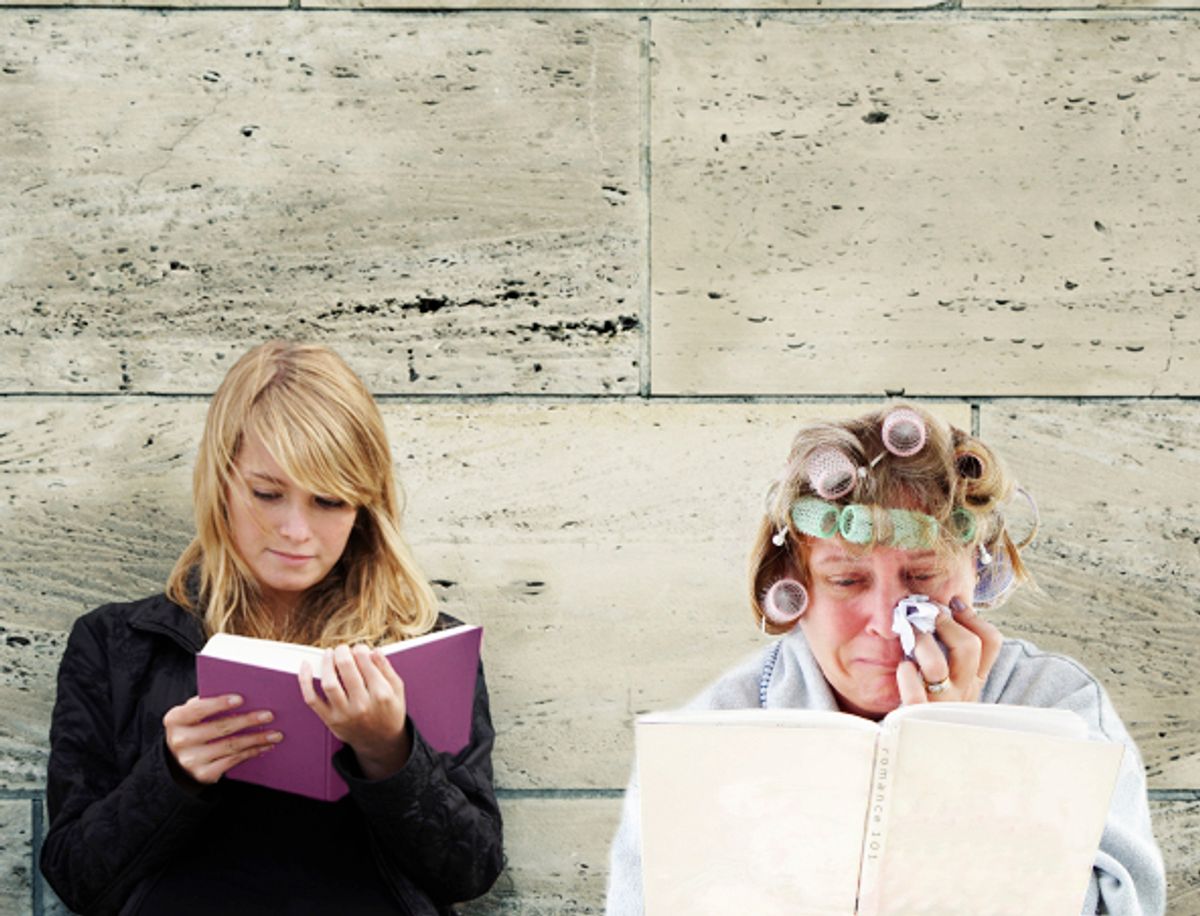

On Thursday, the New York Times' Idea of the Day was: "Is women's fiction plagued by 'misery lit,' obsessed with bereavement, child abuse and rape? Or 'chick lit,' obsessed with Prada handbags and landing the perfect catch? Or is it torn between the two?"

Here's my idea of the day: It's both -- and much more. The Times post references two other articles -- an Independent interview with Daisy Goodwin, who chaired the jury for this year's Orange Prize, and a Standpoint post by author Jessica Duchen -- which frame the debate. Goodwin said of the bleak, issue-driven submissions she read for the Orange Prize -- awarded to the best English-language novel written by a woman in a given year -- "There was very little wit, and no jokes. If I read another sensitive account of a woman coming to terms with bereavement, I was going to slit my wrists." Duchen, who admits she's "working on a novel that's in part, oh dear, a sensitive account of a woman coming to terms with bereavement," counters that if an unusual number of female novelists "have resorted to the tactic of choosing themes that are as dark and miserable as possible," it's probably because "[w]e are sick to death of the assumption that because we are women we must be writing CHICKLIT." Such writers crank up the grim, she says, "So that nobody can possibly consider putting a girly-wurly cover on top of it. So that we have to be taken bloody seriously for a change. Because publishers - who are often women themselves - are perpetrating via their presentation a miserable sexist assumption that women writers only write fluff, and that that is all women readers want to read."

As an avid reader of fiction by and for women, I'm at least partly with both of them. I'm also with Salon book critic Laura Miller, who recently wrote, "American writers in particular are often anxious to be perceived as 'serious,' which they tend to equate with a mournful solemnity. Like most attempts to appear grown-up, it just makes you look childish. Comedy is as essential a lens on the human experience as tragedy, and furthermore it is an excellent ward against pretension." Miller, by the way, was speaking without regard to gender; the tendency to go full-tilt humorless to bolster one's Serious Writer cred is by no means restricted to women. But I think Duchen's absolutely right that the popularity of "chick lit" -- as both a genre and a remarkably tenacious catchphrase -- gives some female writers a special motivation to shroud their stories in unrelenting misery. Let one character crack a joke, and you risk inviting a candy-colored cover and all of the attendant derision.

But then, that derision isn't reserved exclusively for the specific genre known as "chick lit." As Rebecca Traister wrote in 2005, "Beating on 'women's' fiction -- and dismissing certain literary trends as feminine rubbish -- has a history as long as the popular fiction itself." Traister thoroughly documents the charges against chick lit -- including the complaint of a 1999 Orange Prize judge that she had to read entirely too much of it -- but situates them in a long line of rants about the supposed frivolity, excessive sentiment and limited scope of novels written by women. It almost sounds like people's impressions of women's writing are influenced by some long-standing, widespread attitude that women's interests aren't as serious or important as men's -- you think? As for more recent complaints, Goodwin is hardly the first to slam what she calls "misery lit." Have we already forgotten Oprah's original book club, or how her preference for stories about women living through horrific situations contributed to the perception that her taste ran strictly to middlebrow gloom and doom -- and thus, given the club's popularity, so did the average American woman's?

Perhaps that trend is just coming late to the U.K., but here, overwhelmingly grim stories about rape, abuse, lost children and all manner of emotional explosives took off at the same time chick lit did; in the late '90s and early '00s, getting Oprah's imprimatur was the ultimate jackpot for an unknown author and her publisher, but getting a chunk of the Bridget Jones audience was still a pretty big win. So of course everyone and her sister scrambled to produce work that might fall into either category. A decade later, a lot of people are sick of both (as one literary agent puts it, although the genre still does all right, "the term chick lit is taboo and not to be spoken of ever again"), but no other runaway trend has emerged, so here we are still talking about misery lit and chick lit as the defining subgenres of women's fiction -- ignoring everything else women read and write. Which is ... everything else.

Female writers hold the top three spots on the New York Times hardcover fiction bestseller list at this writing. The first, by Jodi Picoult, one of the most successful authors of "women's fiction" going, is about an autistic teenager accused of murder. The second, by first-time novelist Kathryn Stockett, also falls under the "women's fiction" umbrella. It's about the relationships between white families and their black servants in Mississippi in the early 1960s. The third is the 31st book in a crime series by J.D. Robb, aka Nora Roberts, who also churns out romance bestsellers by the dozen. Despite her female protagonists and massive female audience, Roberts writes "genre fiction," not "women's fiction," so she doesn't really count. Nicholas Sparks, on the other hand -- who currently holds three spots on the two paperback bestseller lists -- does count, because his market is primarily women, and his lightweight love stories are not technically romance novels.

Are you seeing the obvious commonalities among Sparks', Picoult's and Stockett's books? Me neither. And are you seeing why Nora Roberts doesn't count as an author of "women's fiction," despite the fact that her audience contains just as many vaginas? Me neither. (Note: Yes, I understand why different categories exist within the publishing industry. What I don't understand is why those distinctions carry over into discussions of "women's fiction" among laypeople.) Chris Cleave's "Little Bee," Robert Goolrick's "A Reliable Wife" and Stieg Larsson's "The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo" are all surely on the trade paperback bestseller list thanks to enormous numbers of female readers -- and if Cleave and Goolrick were women, their books might well be called "women's fiction." It's a term that actually comes in handy when a book defies classification as strictly "literary" or "commercial." But of course one is reluctant to saddle a man with it, unless he's a hearts-and-flowers sap like Sparks.

Now, what if I told you that on the whole, women buy a lot more fiction than men, period? In light of that and all of the above, wouldn't it make sense to consider women the default buyers of fiction, and men the picky niche market? And yet. As with film, the prevailing wisdom is that women like men's stories, but men don't like women's, so dude stuff is universal and chick stuff has a more limited, specific appeal. But a Barnes and Noble bookseller and blogger highlights the problem with trying to define a genre by gender: "Obviously, 'women's fiction' in the broadest sense would be any fictional piece written by a woman or for women. This is too broad a definition for me to adequately wrap my reading and writing around." Me too, honey. Even more to the point: "It's hard to define 'women's fiction', particularly since we don't define 'men's fiction', without sounding like an egotistical, sexist snob."

So. Because "women's fiction" is a category with no clear definition and few recent breakout trends -- but everyone remains convinced it must be a meaningful category -- we're stuck still talking about the phenomenal female-driven success stories of a decade ago as if they're the beginning and end of women's literary tastes. Sure, women are still writing -- and buying -- both "misery lit" and "chick lit," just as men are still writing and buying fiction about war and spies and politics. (As are women.) But suggesting that's all women are writing and reading -- that if the genre of "women's fiction" isn't wholly defined by one or the other, we must be "torn between the two" -- is ridiculous and insulting. Worse, it perpetuates the attitude Traister follows back at least a couple hundred years, that female novelists and their audiences are essentially unserious, that we're primarily drawn to escapist fluff, small-scale relationship dramas, or anything that elicits a good cry, no matter how cheaply. And it's exactly that kind of thinking that makes authors like Duchen go out of their way to "be taken bloody seriously for once" -- only to find that, oops, they're still women writers. So even if they escape the high heels and martini cover trap, they'll get slammed for being too bleak and weepy, too "issue"-oriented, for making the reader feel, in Goodwin's words, "like a social worker by the end of it."

That's not to say Goodwin's wrong to complain about tedious, preachy drama, or that Duchen's wrong to complain about the "miserable sexist assumption that women writers only write fluff, and that that is all women readers want to read." Like I said, to a large extent, I'm with both of them. But the reason I can agree with both is that I don't believe "women's fiction" is essentially about one or the other, nor do I believe either category is all bad. I think there are some real gems among "chick lit," "misery lit," mysteries, thrillers, sci fi, historical fiction -- probably every identifiable genre in existence -- but in each one, there are a lot more forgettable stories and characters than outstanding ones. The problem is, when men publish mediocre books, they're just mediocre books, but when women do the same, they're "what's wrong with women's fiction." Even if nobody has a clue what that term really means, and the only answer to "What kind of fiction do women read?" is "All kinds. And usually in larger numbers than men."

Shares