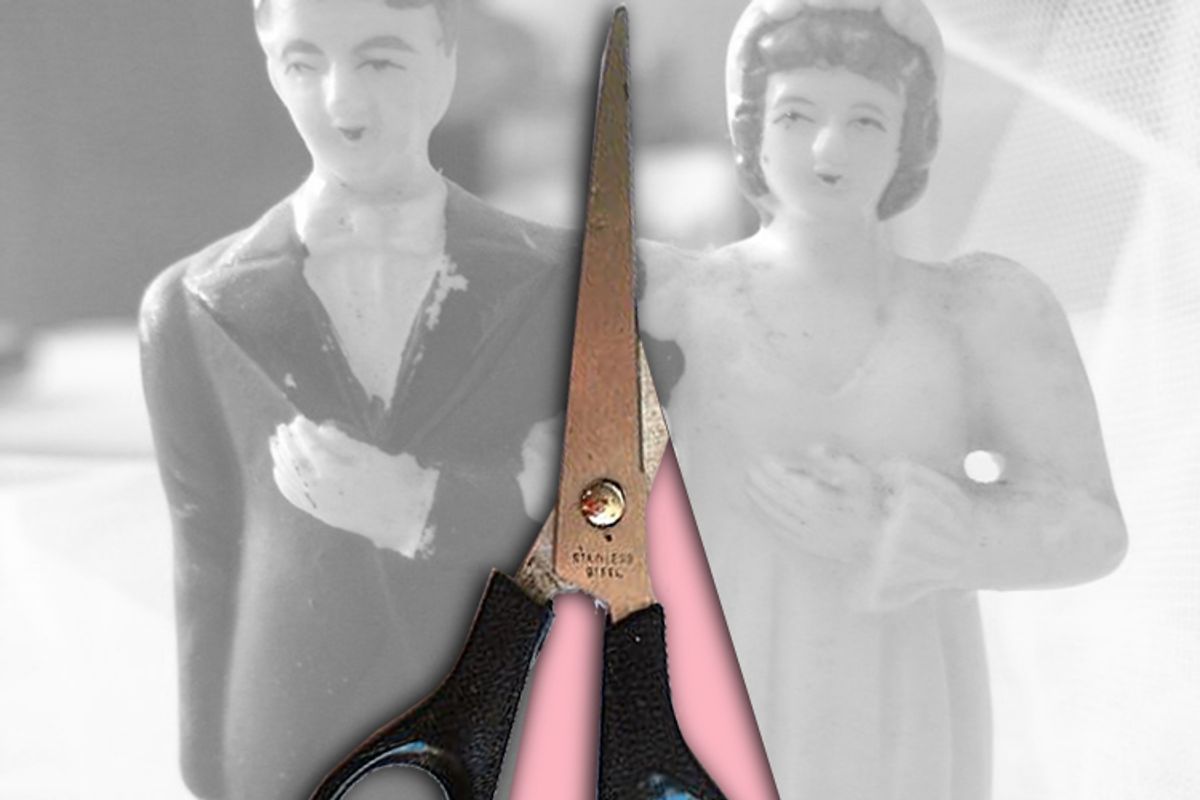

Most married people prefer black and white stories about marriage. We either want a marriage to be blessed by the gods above, fated to endure through whatever crazy obstacles life may bring, or we want a marriage to be doomed to fail, preferably because one party in the marriage is a rat bastard. In either case, it's obvious what the parties involved should do: stay together forever or end it immediately.

People are flawed, of course. Marriages go though rough spells. All spouses have to put up with a lot of annoyances and inconveniences, disappointments small and extra large, but ultimately, it boils down to this: Are you a true match or aren't you? As a wise woman once said to me when I was wavering on my bad relationship with just one of many Mr. Not-Quite-Rights, "If you can't defend it in a court of law, then forget it!"

Although Laura Munson has written a very honest and courageous book about a crisis in her marriage titled "This Is Not the Story You Think It Is" (based on a popular Modern Love essay she wrote for the New York Times), I still find myself wanting her to defend her marriage in a court of law. I write this not to be unfair or unkind -- Munson and her husband do seem to love each other, they have two kids, they've created what sounds like a truly wonderful life for their family in Montana, with so much horseback riding and fishing and tromping through the woods and cooking of elaborate meals that, really, it makes you look at your own impoverished existence, with its Trader Joe's pizzas and its hasty dog walks around the ramshackle neighborhood, and think, Why am I forcing my children to live in this urban squalor?

But then we get to the marriage itself. The author's husband (he is referred to only as "my husband" throughout) tells the author that he's not sure he loves her anymore, then he leaves, saying that he's going to the dump (Is that a hint?) and doesn't come back for a few days. Munson is left to deal with her 12-year-old daughter and her 8-year-old son, somehow not panicking them by bursting into tears, say, or smashing a few dozen plates or just packing everyone up in the van and lighting the whole place on fire and leaving a little note on the front fence that says, "We'll be gone for a little while too, asshole."

No. Instead our intrepid author becomes "strangely serene." She says she is "choosing not to suffer." She is worried. She is struggling. But she knows she loves her husband, and that he can get through this. She will choose to be strong!

Fair enough, until her husband comes back, doesn't apologize, leaves again, stays out all night, comes back, acts like a bratty little dickhead, leaves again ... And all the while, Munson goes through her extreme self-help sports, coaxing herself not to overreact, not to go to a place of anger, not to squeeze the life out of the nearest small animal. Not only does Munson neglect to fuck shit up in any real sense, but instead she spends several (admittedly sweet) chapters remembering her dear old dad (who does sound wonderful), and looking back on her wedding (Rilke and Rumi are quoted a lot. Yes, you've been to that one, too) and considering the strengths of her marriage (they were kindred spirits, they loved adventure, they made space for each other, he called her "the prettiest girl at the party") and reminiscing about her favorite place in the world, Florence, Italy (it does sound pretty great). Munson works very hard trying not to play the victim, and she succeeds. Even though she's written 14 novels that have never been published (passionate or masochistic?), even though her husband is going through a midlife crisis and taking it out on her, she's resolved to take this opportunity to grow, and to learn (passionate or masochistic?).

As exceedingly earnest and unself-consciously new-age kooky as Munson can be, there's no doubt that she's a little ray of sunshine: sweet, funny, sensitive, a great mom, loads of fun. Unfortunately, though, we're offered little proof that her husband is anything but a grumbly little wiener. Munson rolls out all of the appropriate adjectives in her claim that he's a good husband and good father: loving, supportive, etc. But she only goes into rich detail in describing his lowest moments, whether he's leaving her with the kids for the millionth time, or saying things like "I just want a woman who doesn't have any baggage." (You want a man, in other words. Consider skipping the dump and going straight to that bear bar downtown.)

And then, when the author finally gets drunk and makes a big mess -- and who wouldn't, after months of this? -- she skimps on the details! She says, "There was one bad night, when I decided to attach myself to a bottle of vodka." Oh, yes, we think, now we're going to get to the good stuff! No. Our author tells us she can barely remember her "performance," that it was "sloppy and inappropriate." And then? "Fill in the blank with your own best performances." So instead of detailing her drunk flameout (sweet nectar of the gods, yes!) she's back to managing her emotions: "We're human. We screw up. We're going through a brutal time in our lives. It ain't always gonna be pretty." But a big, colorful breakdown could be beautiful, if what we're seeing is a woman who's worked far too hard to maintain control finally admitting that she's vulnerable.

While grace under pressure is certainly something we all aspire to, we can also, most of us, relate to that moment when a relationship is falling apart, but we're seized by the notion that we can steer it away from the jagged rocks just by being a little bit better than we are right now. Munson's psychological back flips bring me back to all the times I tried to control my emotions and improve myself for the sake of Mr. Not Quite Right. All of that taking the higher ground, rising above it, giving space, concentrating on my own "work," living in the now, making non-blaming statements about my feelings -- it usually added up to me extending the life of a relationship that was just begging to be put out of its misery. If a relationship requires emotional overachieving on your part, if you're holding your breath and twisting yourself into an unfamiliar pretzel of yogic forgiveness and wonderment? I'm not sure most of us can stay in that position for the rest of our lives without doing permanent damage to our spleens and our self-esteem.

On the other hand, married people can be pretty intolerant of ambiguity in relationships. Think about how most of us freaked out over Sandra Tsing Loh ditching her husband after all those years of marriage. We felt betrayed, because Tsing Loh sold us on that marriage. We believed in those two, we loved her darling musician husband, how he played with their two little girls. They were living an endearing little scrappy fairy tale artist's life, as far as we were concerned. Who knows what life in their house was really like? Her husband traveled all the time. Nothing is harder on a partnership than that. But we loved that guy -- of course we loved him! Tsing Loh is a wonderful enough writer that she could make a throw pillow sound beguiling.

As much as I want Munson to transform her throw pillow of a husband into someone who sounds mildly appealing, let alone beguiling, my need to like him is probably typical of the way most married people digest stories about marriage, whether they're "Eat, Pray, Love"-style memoirs of a marriage crisis like Munson's or just divorce anecdotes from a friend of a friend. These sorts of stories turn us into the worst sorts of judgmental, blaming harpies, the exact sorts of people that Munson is quite valiantly refusing to become.

And really, who the hell are we to judge? You can never know how another person's marriage works, even if that person is a very close friend. A dynamic that appears toxic might function perfectly well behind closed doors. Sure, we think we know who's the angel and who's the rat bastard, but chances are we really don't have a clue. In the end, it's always best to keep our fat mouths shut.

Munson, for one, resolves to forget the battles and the suffering and the tit for tat. Marriage is hard, after all, and a spirit of gratitude and a refusal to abandon ourselves to our most turbulent emotions goes a long way. Ultimately, maybe the traits of the two people in a marriage aren't nearly as important as their ability to suspend their disbelief together, to imagine that they've been blessed by the gods above, fated to endure through whatever crazy obstacles life may bring.

Shares