There are better ways to spend one's time than listening to Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein try to explain to Sen. John McCain just what exactly is a "synthetic CDO." A Martian invader would have a better chance of teaching trigonometry to a baboon. What had once been riveting television was now a grind. By the time Blankfein made his culminating appearance at around 6:30 p.m. at Tuesday's marathon congressional hearings investigating all things Goldman, I'm guessing that anyone who had been in attendance since 10 a.m. was beginning to feel as battered and bludgeoned as the long line of beleaguered Goldman execs who had presented themselves for ritual senatorial abuse.

There are only so many times you can hear a Senate subcommittee chairman spit out the words "shitty deal" before the thrill is gone. Claire McCaskill's spitting-mad rage in the morning had been replaced by John McCain's somnolent imitation of a walking corpse in the early evening.

But give credit to Goldman Sachs for one thing -- consistency. From top to bottom, from CEO Blankfein to CDO market maker Fabrice Tourre, Goldman Sachs executives all testified under oath that they did nothing unethical during the financial crisis, that it was totally fit and proper to engineer synthetic confabulations of risky loans and sell them off to investors while betting their own money on the likelihood that those securities would decline in value.

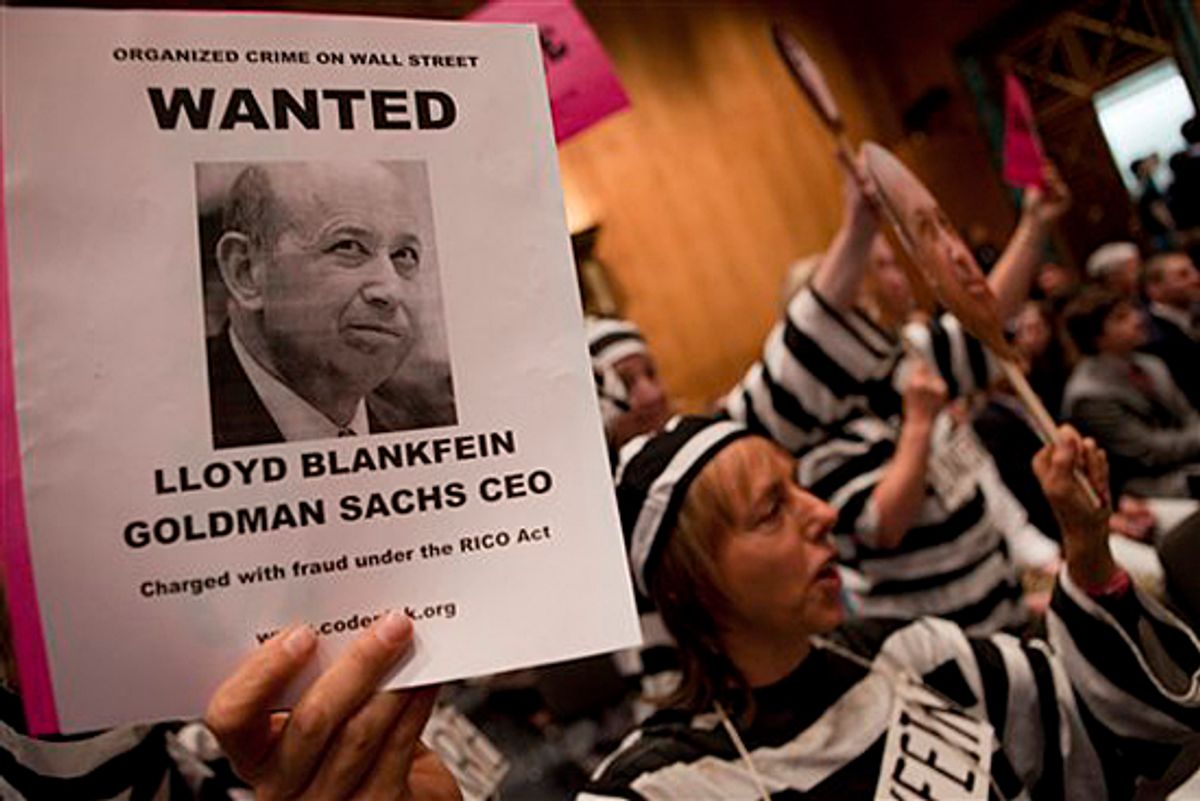

Blankfein acted as if he didn't even understand the theory that there might be a conflict of interest involved in this process, no matter how many times an increasingly frustrated Carl Levin raised the possibility. Blankfein has a way of screwing up one side of his face into a twisted knot that is half-incredulous and half-incomprehending, as if he simply can't believe what he is hearing. Suffice to say, that particular expression made numerous appearances.

"I don't think our clients care, or should care," what Goldman's positions were on the securities that Goldman helped its clients buy or sell, said Blankfein. As far as Blankfein sees it, clients come to Goldman looking for exposure to a certain level of risk, Goldman gives it to them, and then the chips fall where they may.

But the back and forth between Levin and Blankfein over whether such behavior was acceptable or ethical seemed to miss a much larger point. The trickle-down effect of Wall Street's voracious appetite for high-yielding risk -- of all those clients coming to Goldman Sachs and all the other investment banks begging for slices of synthetic CDOs -- wreaked total havoc on the American economy by fueling irresponsible lending and an out-of-control housing bubble. The net effect of the trader mentality held so dear by Goldman Sachs was to derail Main Street. Without meaning to, we all became counterparties to Goldman's trades, and like it or not, we all now care, and should care, what banks like Goldman Sachs are up to.

Shares