I took a social psychology night class in college. I wanted to experience a classroom filled with people who dressed in business clothes and took their education seriously. It didn't hurt that class met only once a week, in the same building as my apartment.

Class attendance and participation counted. In lieu of a final exam, there would be one written paper -- a discussion of an experiment that encompassed the entire semester and demonstrated our understanding of psychological theory.

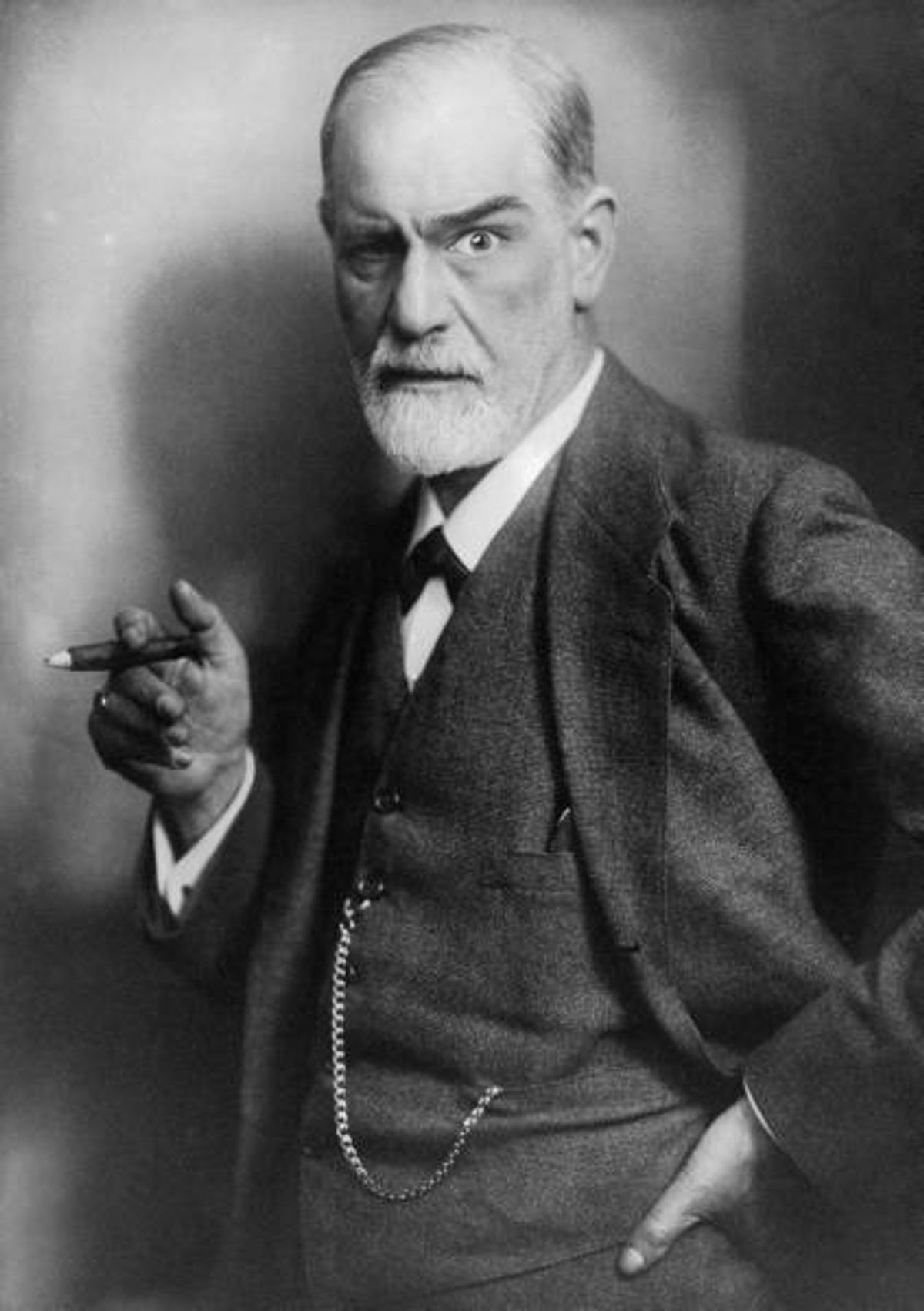

The professor was pompous, but I marveled at the different night-class dynamic. Front seats were claimed quickly, hands were raised often, and students argued in their most pretentious vocabulary. I smelled perfume, cologne, diesel fuel. As interesting as my classmates were with their Maslow-Freud sound bites, I was still a teenager whose distractibility index increased as the day wore on. By the third week I'd cut class to play guitar.

I stopped paying attention, stopped raising my hand, and took to writing in my journal where I recorded all the important stuff in my life -- lyrics, story ideas, phone numbers of guys I met at the student center. After cutting two more classes I panicked. I visited the professor to say I hadn't been feeling well but promised I would be at every class. He told me not to worry. Then, shocking even myself, I cut one more.

I visited the professor yet again. To my surprise, he took pity on me and told me he'd wipe the slate clean.

When exam week rolled around, I hadn't even thought up an experiment, let alone started my paper. I was busy bemoaning my fate, criticizing the psychologists I had read outside of class, and hoping some idea would eureka me overnight.

I was smart enough to know I needed help. And while most of my friends were tossing out useless terms like "incomplete," one of them suggested a brilliant idea: I should do the experiment on my teacher. I could use all my bad behavior, missing class, not participating, visiting him with stories of illness. I could show how I attempted to modify his behavior and support it all with my knowledge of psychological theory. Just thinking of it now makes me nervous.

I wrote the hell out of the paper. I included dates, times and conversations from my meetings with the professor. I gave him my Skinnerian best. I discussed the experiment with a few of his colleagues who loved the idea. They suggested a refined premise: I was trying to prod him into becoming more authoritarian, but he was just too true to his kind nature.

I wrote like a madwoman. I checked my textbooks and filled in every last detail. Somehow I got the courage to hand it in. And then the professor announced that we would all discuss each other's papers next week.

I ran back to my apartment and nearly cried. My classmates were eager to pull apart anyone who so much as posed an alternative theory. They would humiliate me en masse.

I went back to all my helpers. They shrugged.

This was their advice: Cut another class; you're really good at that.

I went back to the guy who concocted the idea. "Sell it," he told me. "Don't blink."

I decided to face the consequences. I walked weak-kneed into the three-hour class and made it through the break with no mention of my paper. The last half-hour ticked by in heartbeats and prayers. Finally, with 10 minutes remaining, my professor said he had saved one paper for last. I could feel the blood drain from my face as he walked toward me. He placed the paper on my desk and announced to everyone that I had done my experiment on him.

All eyes were on me. He asked me to talk about my paper. So I did. Light-headed and nauseous, I told the class all about it, how I missed class on purpose, kept journals, visited the professor. The room didn't spin but I was getting the evil eye from Freud, Skinner, Jung, Maslow -- even Linda Goodman in the back row. This was not a jury of my peers.

The politically charged argumentative genius in the front finally asked the question, "How do you grade something like that?"

My professor instructed me to turn my paper over.

"It's an A," I said.

Even bigger gasps. I jogged to the elevator. I knew I'd be lucky to get out of there with my life.

There was a note on my paper: "Even though your experiment was a failure and you were unable to change my behavior, it was the most interesting one I've ever read."

But I did learn one thing about social psychology that semester. You can never overestimate someone's ego.

Shares