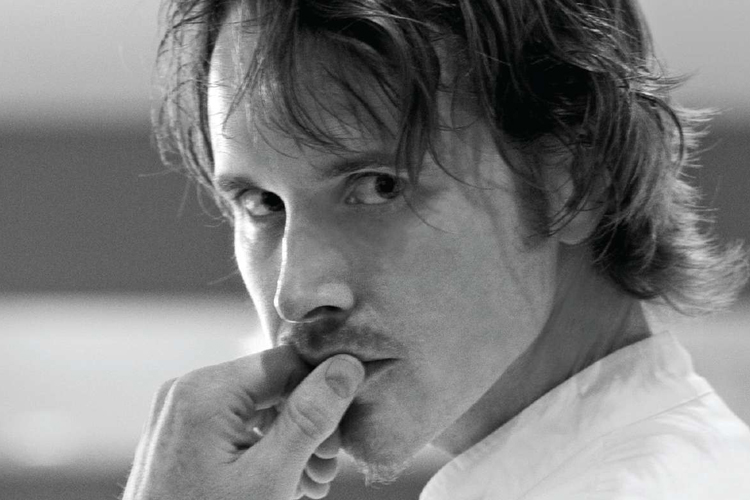

At some point during my first meal at Grant Achatz’s restaurant Alinea, I started giggling. There had been no joke — I just started giggling. Soon, I was bouncing up and down in my seat, laughing almost uncontrollably, and then suddenly teetered on the edge where I didn’t know if I might start crying. I was, as they say, emotional, and I couldn’t exactly say why. Three years later, I returned with my special ladyfriend, and, at some point during our dinner, she took a bite, skipped the giggling, and just started crying. And looking around the room, we were not the only ones to feel this way. I don’t use this word lightly, but it takes a genius to create meals like that.

Still, even beyond the stunning creativity, intelligence and emotional expression in his work, it may be because of Grant Achatz’s biography that he will become a household name. Growing up in a diner family in small-town Michigan, he was cooking at 5, and in the diner kitchen at 11. By high school, he knew he wanted to be a chef, a great one. After culinary school, he wrote the then still-obscure chef Thomas Keller at the French Laundry in Napa Valley a letter every day for weeks, until Keller took him on as a cook — and under his wing — as that restaurant was becoming known as the “most exciting place to eat in the United States.” Four years later, Achatz was running his own kitchen, and a just few years after that, his own restaurant, Alinea, was called the best restaurant in the country by Gourmet magazine and its editor, Ruth Reichl — who put Keller on the map with that pronouncement years before. But then — and this is the movie stuff — Achatz was diagnosed with tongue cancer. Yes, tongue cancer, and bad; he was given just months to live.

His memoir, “Life, on the Line,” was published last week: a story of being utterly driven, of finding and focusing creativity, and of friendship and survival. He spoke candidly with Salon over the phone about how you can be a great chef and not enjoy food, his creative process while he lost his sense of taste, and on how his drive has burned and rebuilt bridges.

There’s often an assumption that chefs have to be obsessed with eating food. And so I was struck by a comment I read by a chef who cooked with you at the French Laundry, back when it was first hailed as the best restaurant in America by the New York Times. He said that you ate very little fat, only lean meat and egg whites because you were a health nut. How can you eat like that and be a great chef?

Well, there are so many ways to look at food. In all honesty, there was no pleasure in eating like that. Boneless, skinless, boiled chicken breast? It’s really not that good. But what that afforded me was pleasure in something else — I was a workout freak. I was competitive in that area. You set a goal, you achieve it, goal, achieve, goal, achieve. Eating like that wasn’t about flavor, it was about the pleasure of attaining a different kind goal.

But you can still approach cooking and food in an evaluative, focused way. I could still taste and evaluate that sauce I was making. I didn’t necessarily enjoy that spoonful of sauce while I was pouring sweat cooking on the line, 95 degrees, but I could taste it and tell that somebody three minutes later, in the dining room on their anniversary, would really enjoy it.

My food has to be delicious, first and foremost, but so much of the experience is about other things. If Heather and I come across some figs, she might eat it and think, “Oh my God,” and I might be thinking, “Yeah, it could be better with a little salt, crack of black pepper, and balsamic vinegar.” But if we’re in the Napa Valley, taking a walk, find them on a tree … the figs are just going to be better than if you seasoned them “perfectly.” Ultimately the perfect meal is when those things come together – circumstance, the food, ambiance, and you’re with the person that you want to be with.

It’s one thing, though, to be eating bland food by choice, but you later lost your sense of taste for months during your cancer treatment. In your memoir, you wrote that you grew to almost hate eating, not just because it was physically painful, but because when you couldn’t taste the food, the sensation was just full of loss — what you couldn’t do. How did your cooking and your creative process change at that time? How did it feel different?

Well, the sense of satisfaction was much different. Once, we got some amazing artisan shoyu [Japanese soy sauce]. I smelled it, and could detect coffee and chocolate, and said, “We’re going to make a dessert with this.” Jeff [Pikus, who was Achatz’s second-in-command during his treatment] was like, “He’s lost his freaking mind. Way too much Vicodin.” So I made him smell the sauce and the chocolate. I had to talk him into why it might taste good. And then when we put it on the plate, I had to ask him, “Does it taste good?” You’re never really in that position as a cook, not knowing.

So the satisfaction was intellectual, but the big payoff moment of putting that first spoonful in your mouth isn’t there.

In some ways, it was more satisfying, because you’re tuning into something that you didn’t before. And we developed far more collaboration, far more trust.

Another thing, too. When I was just getting my sense of taste back after treatment, I can probably say that the food at Alinea was too sweet.

When my taste was gone, I was hyper, hyper, trying to tune into it. My taste eventually came back in stages: first sweet, then bitter, then acid, then salty. But when that was starting to happen, I noticed myself using a lot more bitter flavors. I was never a bitter flavor lover, but post treatment, just because I could discern it, I was putting it in everything. I yearned to have the satisfaction of tasting something, anything, so I used a lot of sweet and bitter flavors, just so I could taste it. But eventually, it really, really made me understand taste, and the way components come together. Because we never normally have the opportunity to isolate taste.

There’s this old cliché that the Chinese have a proverb, “May you live in interesting times,” and you can never tell if it’s a blessing or a curse. So you’re young, you’ve reached the heights of your field, survived life- and career-threatening cancer, but you write in the epilogue of the book that coming back to “normal” life after treatment was the hardest part. Why?

My personality was always such that I always look straight forward, never behind or to the side. I compartmentalized. Anything that could ever prevent me from achieving a goal, I put in a box, tape it up, throw it over my shoulder. You aim for a goal and attain it. Then you look to the next one.

Then something like this happens, you get incredibly lucky with a great medical team. You make it. Then you come back to work and you’re like, OK. When I was at Trio [Achatz’s first kitchen], the goal was to get a four-star review in the paper. Done. At, Alinea the goal was to get Ruth Reichl to call you best restaurant in the country. Done. Then it’s to be in the Restaurant magazine top 50 in the world, and you get that. And then you might die, you beat that … and then what? What do those stars mean now? What do you have to achieve?

It shorted my system, and I went into a panic, like, “Whatever happens at this point, will I ever get satisfaction from it?” The competitive side of me felt like there would never be a great challenge anymore. Then I got into this weird place mentally, where all the sacrifice, all the work, guys grinding it out — for what? So what? Everything I ever believed in, everything that was important, completely got lost. And all I saw was the grind of it.

After I hit that low, I spent a couple weeks at that low. Pikus quit. The guy was the ultimate soldier. He worked at Trio, helped us make the “best restaurant in the country,” led Alinea through the most difficult time. He soldiered through all of that. Then one day, after my treatment was over, we were working on developing a new dish together when he imploded and walked out. He looked up at me, said, “I can’t do this.” Our eyes met for a second and I said, “OK.” After that, I just looked back down on the dish and thought, “I gotta get this on the menu tonight.” But then I was invigorated by the challenge. It went on the menu that night. That’s what it’s all about. It’s not about achieving, it’s about trying to achieve. Now I realize that it wasn’t until I saw someone else lose focus that I realize how much I’d lost focus too. During that low period, I was like, “Screw this, screw them.” And when I saw him have that attitude, I finally saw it in myself too. And the first time I talked to him, two and a half years later, was a month ago.

Speaking of strained relationships, there’s a lot been made of your chapter about working briefly for Charlie Trotter, the other Chicago chef whom many have long considered to be among the best in the world. You idolized him from reading his books, worked with him for a few months, but had a couple of icy exchanges during that time. And when you tried to talk to him about wanting to leave, he basically said, “If you leave without working here a year, I don’t know you.”

Well, a lot of what people reading the book are like, “Oh man, I bet Trotter is pissed off.” For me, as a young cook, that experience was disheartening. But it’s not like he’s a monster! He’s a perfectionist who won’t let anything get in his way. And I told those stories to draw parallels to my own personality. His “If you leave now …” was really just like my, “Fuck Pikus. You walk out the back door, you’re gone.” I’m not trying to get back at the guy. I was a 22-year-old cook. A lot of people are trying to pit the two of us against each other, but that’s not what it’s about. He’s on an all-out assault to make the best restaurant in the world. If there’s one thing I regret in the book is that I don’t show enough that I respect him, as a chef that’s completely driven.

And then there’s another story of strained relationships that doesn’t necessarily get resolved in your memoir. You tell the story of being 14 and building your first car with your dad. Later, we find that there are problems in your family, and you don’t talk to him for many years. So why is the story of building the GTO so prominent in the book, and in your mind? I’ve heard you tell the same story to aspiring chefs.

Well, there are so many parallels between that experience and being a chef. Putting the car together is like organizing a kitchen. I didn’t know that then. But when we were building Alinea, I kept drawing back on that experience. The most important thing is that it’s hard work. You want something that’s great? Build it yourself, actually reap the tangible benefits of it. I was 16 years old, and I had the coolest car in town from a $1,400, literal piece of junk to something great. That’s the critical thing.

My dad and I built that thing from scratch, over two years, to show condition. But when my parents got divorced for the second time, I said to my mother, “I don’t really give a shit what you do with the car.” So she sold it to my cousin. It totally went out of my consciousness.

Then in the book, there’s a story about your father coming into Alinea randomly one day, but we don’t get to see how that meeting goes.

That was the first time I’d seen him in 10 years or something, and you have all that residual resentment. Part of me thought it would even take too much effort to repair a relationship at that point. So he agreed to come in for dinner, but I said, “Oh, he won’t get it, he won’t even like it.” That was me emotionally protecting myself: “If he doesn’t understand this food, he won’t understand me.” But he had dinner, had my food, and he got emotional. He got it. We talked about it for a long time after his meal. And that … that was the starting point of our relationship again.

Postscript: For the release party of “Life, on the Line,” Grant’s business partner (and co-author) Nick Kokonas found the old GTO and had it rebuilt as a surprise. Grant’s father was at the party, too.