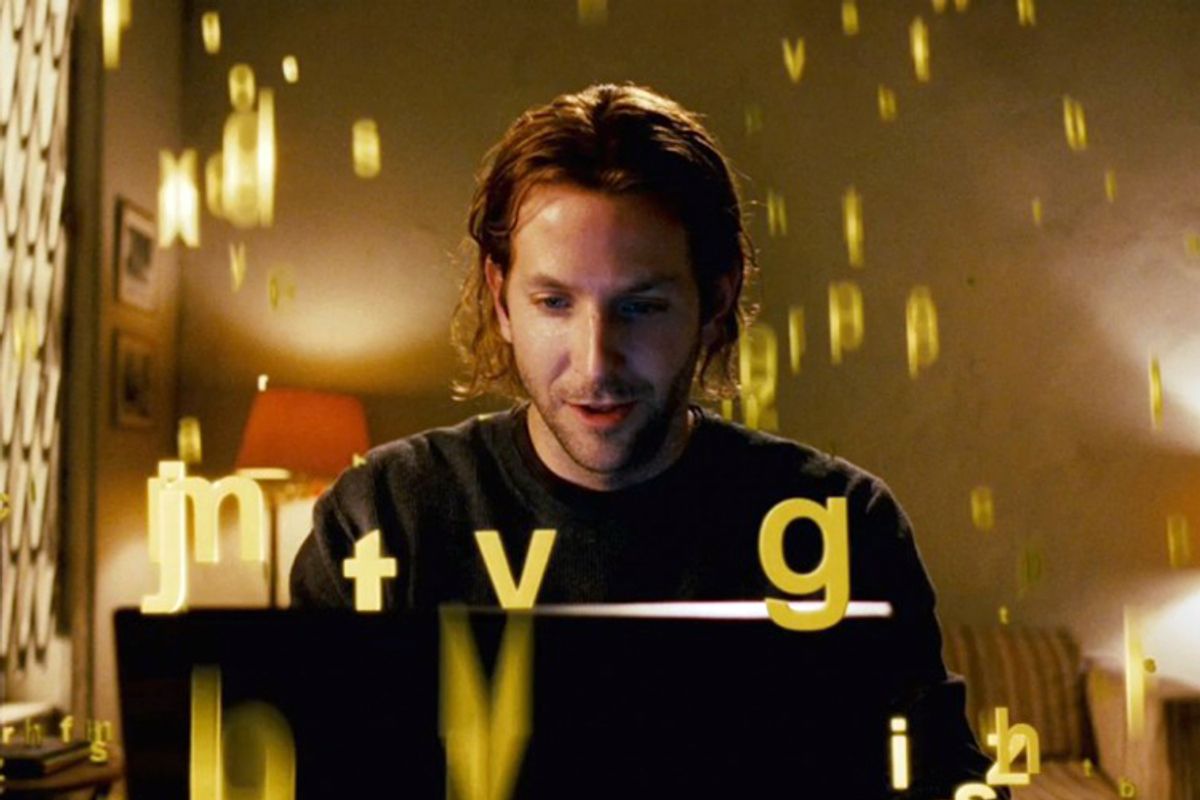

"Limitless," a deeply stupid Bradley Cooper vehicle about a frustrated novelist who gets his hands on an experimental drug that kicks his IQ up to the "four digit" range, is only the latest example of Hollywood's long fascination with writer's block. From "Barton Fink" to "Adaptation," the tortured spectacle of a writer who cannot write has proven much more fun to watch than one who can.

Blocked writers tear out their hair, turn to drink and go noisily mad, all of which are dramatic; the image of someone busily tapping on a keyboard is not. Furthermore, blocked writers always want to go off to a secluded cabin or beach house or snowed-in hotel, where something terrible will inevitably happen ("Secret Window," "Bag of Bones" and, of course, "The Shining" -- all based on works by Stephen King, who seems way too prolific to have ever wrestled with block himself).

However, the hero of "Limitless," Eddie Morra, is the only cinematic writer I'm aware of who cures his block pharmaceutically -- the booze that so many of the others resort to is more along the lines of drown-your-sorrows self-medication. Essentially, the drug turns Eddie into what a person suffering from a manic episode only thinks he is: a self-confident superman who picks up a new language in an afternoon and finishes a brilliant novel in four days. (See also: cocaine.) It does this by activating the fabled nine-tenths of the brain that the rest of us purportedly don't use.

What's especially bizarre about this premise is the notion that writer's block can be overcome by an increase in intelligence. (More plausibly, Eddie, once he gets really, really smart, decides to bail on writing books entirely.) It would be hard to find a blocked writer who thought that brains were exactly what he or she lacked. In her fascinating 2004 book, "The Midnight Disease: The Drive to Write, Writer's Block, and the Creative Brain," neurologist Alice Weaver Flaherty explains that the impulse to create is rooted in the limbic brain, the seat of instinct, not in the cerebral cortex, which performs the analytical activities enhanced by Eddie's pills.

Yet, like Eddie, Flaherty found that medication played a role in her own struggles with writing. She suffered two separate incidents of postpartum mood disorder, not just a crushing period of writer's block but, before that, a more exotic condition called hypergraphia: writing too much. In the grips of this compulsion, she wrote constantly, to the point that it "felt like a disease: I could not stop and it sucked me away from family and friends." She wrote when she should have been working and responded to the sight of a keyboard or blank page like a crackhead laying eyes on a pipe. The mood stabilizer she took to correct the hypergraphia was what gave her the writer's block.

Throughout, Flaherty was dismayed to find that what seemed to her "one of the most refined, even transcendent talents, should be so influenced by biology." Seven years after the publication of "The Midnight Disease" this hardly seems worth remarking on; many patients on antidepressants report a decrease in creative drive as a side effect.

Most cases of writer's block are not, however, the result of a biochemical imbalance. Those not caused by being, as Eddie puts it, "depressed off my ass," are more likely to be rooted in fear. It's here that something called the Yerkes-Dodson Law applies. First proposed by two psychologists in 1908, this principle holds that the more "aroused" (i.e., engaged and challenged) a person is by a task, the better he or she performs, up to the point that the arousal becomes anxiety or worry, at which point performance declines.

In other words, beyond a certain point, the more difficult a writing task, and the more you think it matters, the more likely you are to become blocked. This may explain why journalists with, say, two deadlines per week almost never get blocked: no individual story ever has to carry that much weight. (The paycheck helps a lot, too. Not long ago, a woman sitting next to me on a plane asked if I had a trick for getting past writer's block, and I replied, "Yes. It's called a mortgage.")

One reason blocked writers make great movie characters is that most Americans seem to think they have at least one book in them. "I've got a fantastic idea," they say. "I just need to find the time to write it all down." Ah yes, there's the rub. And if they never quite get around to it, they can still identify with someone like Eddie, a guy with a similar gold mine locked inside him who got lucky enough to stumble upon the perfect key. These are the low-arousal low-performers, people who like to fantasize about being an author but who lack the motivation to power themselves through the drudgery of actually writing a book.

The high-arousal low-performers are more desperate cases. They believe that writing the right book (or screenplay) will transform their lives and remake their identities, and with so much riding on the outcome, they choke. All of Hollywood's blocked writers belong to this category: Their careers, marriages, houses -- whatever -- always seem to be hanging in the balance.

While overwrought, such scenarios have a subjective truth; the stakes fuel the block. Some of the most famously "blocked" writers, such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge, wrote reams of stuff -- just not the stuff they thought they ought to be writing. It's amazing what you can get done when you believe you're shirking some other, more important enterprise.

That's what every blocked writer really needs: something more significant they should be doing instead, an earth-shaking, life-changing project you're stealing time from to work on this little novel. Or the great novel you ought to be drafting while you knock off your memoir just for fun. Granted, inventing such a decoy project and convincing yourself that you may actually get around to it someday requires a bold and sustained act of imagination. But that's what writers do, isn't it -- make stuff up?

Shares