Did enhanced interrogation techniques -- "torture" -- lead us to Osama bin Laden?

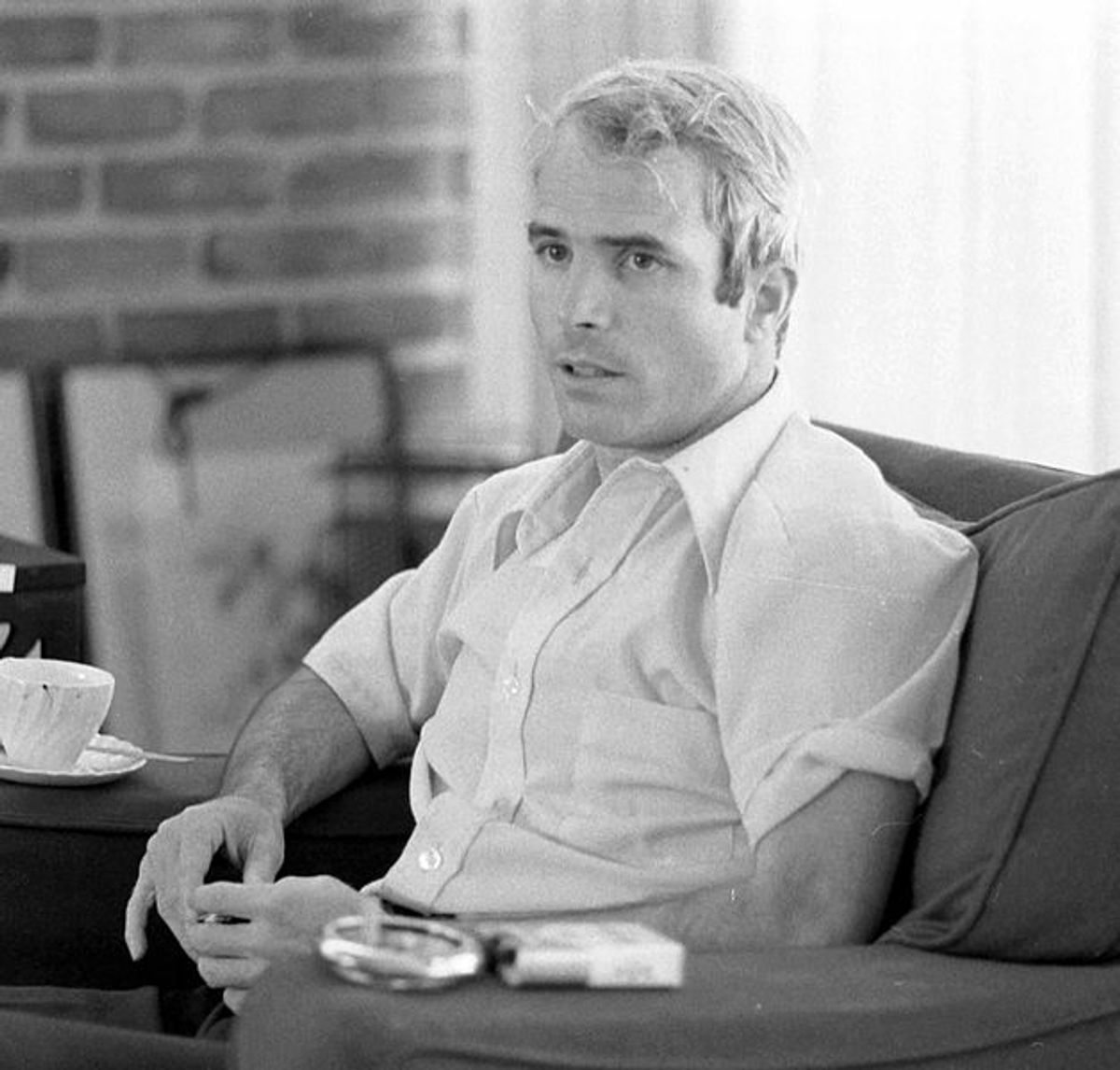

The question has been addressed frequently in the past week and a half, by everyone from John Yoo to Glenn Greenwald. The latest public figure to express his opinion on the matter is Arizona Senator John McCain.

In a Washington Post op-ed on Thursday, McCain pushed back powerfully against those on the right, such as former Bush administration Attorney General Michael Mukasey, who suggest that information obtained through torture helped American forces to pinpoint bin Laden.

McCain writes:

I asked CIA Director Leon Panetta for the facts, and he told me the following: The trail to bin Laden did not begin with a disclosure from Khalid Sheik Mohammed, who was waterboarded 183 times. The first mention of Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti -- the nickname of the al-Qaeda courier who ultimately led us to bin Laden -- as well as a description of him as an important member of al-Qaeda, came from a detainee held in another country, who we believe was not tortured. None of the three detainees who were waterboarded provided Abu Ahmed’s real name, his whereabouts or an accurate description of his role in al-Qaeda. In fact, the use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” on Khalid Sheik Mohammed produced false and misleading information.

He goes on to make a more personal point:

I know from personal experience that the abuse of prisoners ... often produces bad intelligence because under torture a person will say anything he thinks his captors want to hear -- true or false -- if he believes it will relieve his suffering. Often, information provided to stop the torture is deliberately misleading.

As is well known, the senator was a prisoner of war in North Vietnam for more than five years, during which time he suffered both physical and psychological torture. In an account published in U.S. News in 1973, he explained that he had provided a false confession himself after reaching his "breaking point:"

They wanted a statement saying that I was sorry for the crimes that I had committed against North Vietnamese people and that I was grateful for the treatment that I had received from them. ...

I held out for four days. Finally, I reached the lowest point of my 5½ years in North Vietnam. I was at the point of suicide, because I saw that I was reaching the end of my rope.

I said, O.K., I'll write for them.

They took me up into one of the interrogation rooms, and for the next 12 hours we wrote and rewrote. The North Vietnamese interrogator, who was pretty stupid, wrote the final confession, and I signed it. It was in their language, and spoke about black crimes, and other generalities. It was unacceptable to them. But I felt just terrible about it. I kept saying to myself, "Oh, God, I really didn't have any choice." I had learned what we all learned over there: Every man has his breaking point. I had reached mine.

Shares