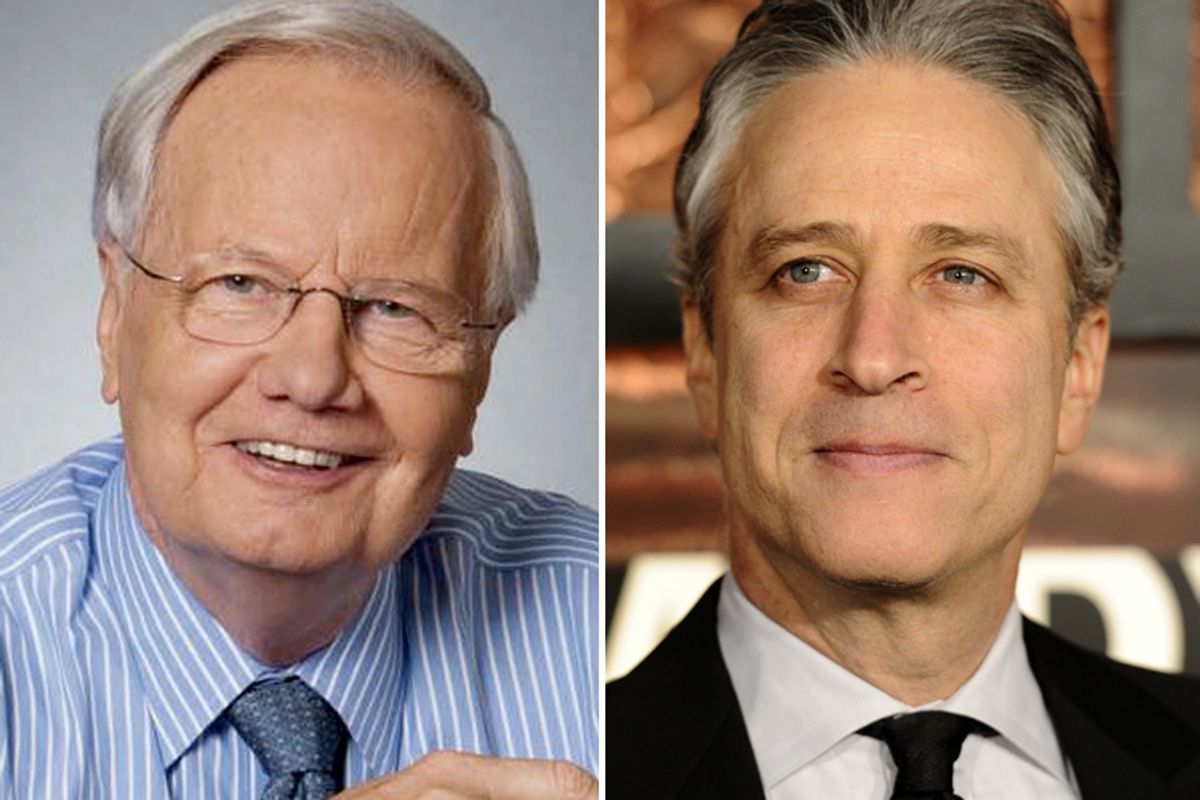

Someone asked why I invited Jon Stewart to be the first guest on the Journal's premiere in 2007. "Because Mark Twain isn't available," I answered. I was serious. Like Twain, Stewart has proven that truth is more digestible when it's marinated in humor.

He and his writers craft political commentary the way Stradivarius made violins. Exquisitely. Just watch "The Daily Show." Or, on a dark and stormy night, when the news from Washington has your stomach churning and your nerves jangling, dip into their book, "America (The Book): A Citizen's Guide to Democracy Inaction." You will instantly feel better. My favorite entry is their "inspirational" story of how the media "transformed itself from a mere public necessity into an entertaining profit center for ever-expanding corporate empires." Unfortunately, this account will make you weep as much as laugh. Stewart regularly reminds us how the press botches the world, often deliberately. Witness his spot-on put-downs of Fox News, CNBC's coverage of the global financial crisis, and the vapid bombast of CNN's late and unlamented "Crossfire," which came to an end soon after Stewart appeared on it and said, in effect, "Shame on you!"

"The Daily Show's" humor would be funny enough even if it weren't true, but truth is satire's spermatozoon, and where it lands it leaves us not only laughing but thinking. Jon Stewart says he is just a comic, but I don't think so. Look at his appeal to people who are alienated from American electoral politics. The "Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear" that he and Stephen Colbert threw in Washington the Saturday before Election Day 2010 drew a quarter of a million people to the National Mall. His on-air support -- and scathing attacks on opponents -- of the healthcare legislation for 9/11 responders was considered critical to its passage by Congress. An appearance on "The Daily Show" has become a campaign stop for any national candidate willing to face Stewart's barbed but respectful -- and always well-informed -- questioning.

Three days before Stewart appeared on the premiere of the "Journal," he interviewed Sen. John McCain on "The Daily Show." McCain, in fact, had been his most frequent political guest, but this was surely one appearance he would like to take back. The senator had just returned from a visit to Iraq and he began the conversation with a "one of the boys" joke about planting an IED -- the insurgents' weapon of choice against American soldiers -- under Stewart's desk. There were groans from the audience. Stewart then went to work on him with the skeptic's scalpel, and McCain, seemingly baffled by the facts of the war so readily brandished by Stewart, withered before our eyes. When the interview ended, one could imagine the inept candidate for president that McCain would turn out to be. It took Stewart to reveal what over the years the Sunday talk shows had helped McCain to conceal -- that he was just another flesh-and-blood politician, skilled at manipulating the press to serve his own ambition, and not the anticipated messiah.

A few years ago, Leslie Moonves, the president of CBS, said he could foresee a time when Stewart would replace Katie Couric as anchor of CBS Evening News. In fact, when Americans were asked to name the journalist they most admired, Stewart was right up there -- tied in the rankings with Brian Williams, Tom Brokaw, Dan Rather and Anderson Cooper.

No kidding.

-- Bill Moyers

You've said many times, "I don't want to be a journalist, I'm not a journalist."

And we're not.

But you're acting like one. You've assumed that role. The young people who work with me now think they get better journalism from you than they do from the Sunday morning talk shows.

I can assure them they're not getting any journalism from us. If anything, when they watch our program we're a prism into people's own ideologies. This is just our take.

But it isn't just you. Sometimes you'll start a riff, you'll start down the path of a joke, and it's about Bush or about Cheney, and your live audience will get it, they'll start applauding even before they know the punch line. And I'm thinking, "OK, they get it. That's half the country." What about the other half of the country -- are they paying attention? If they are, do they get it?

We have very interesting reactions to our show. People are constantly saying, "Your show is so funny, until you made a joke about global warming, which is a serious issue, and I can't believe you did that. And I am never watching your show again." You know, people don't understand that we're not warriors for their cause. We're a group of people who write jokes about the absurdity that we see in government and the world and all that, and that's it.

We watched the McCain interview you did. Something was going on in that interview that I have not seen in any other interview you've done with a political figure. You kept after him. What was going on in your head?

In my head?

Yes.

"Are his arms long enough to connect with me if he comes across the table?" I don't particularly enjoy those types of interviews, because I have a great respect for Sen. McCain, and I hate the idea that our conversation became just two people sort of talking over each other, at one point. But I also, in my head, thought I would love to do an interview where the talking points of Iraq are sort of deconstructed -- sort of the idea of, "Is this really the conversation we're having about this war, that if we don't defeat al-Qaida in Iraq, they'll follow us home? That to support the troops means not to question that the surge could work? That what we're really seeing in Iraq is not a terrible war, but in fact just the media's portrayal of it?"

I saw McCain shrivel.

Eight minutes on "The Daily Show."

But something happened. You saw it happen to him. What you saw was evasive action.

He stopped connecting and just looked at my chest and decided, "I'm just going to continue to talk about honor and duty and the families should be proud," all the things that are cudgels emotionally to keep us from the conversation, but things that weren't relevant to what we were talking about.

So many people seem to want just what you did, somebody to cut through the talking points and get our politicians to talk candidly and frankly.

Not that many people. You've seen our ratings. Some people want it. A couple of people download it from iTunes. The conversation that the Senate and the House are having with the president is very similar to the conversation that McCain and I were having, which was two people talking over each other and nobody really addressing the underlying issues of what kind of country do we want to be, moving forward in this? And it's not about being a pacifist or suggesting that you can never have a military solution to things. It's just that it appears that this is not the smart way to fight this threat.

Your persistence and his inability to answer without the talking points did get to the truth: that there's a contradiction to what's going on in that war that they can't talk about.

That's right. There is an enormous contradiction, and it is readily apparent if you just walk through a simple sort of logic and simple rational points. But the thing that they don't realize is that everyone wants them to come from beyond that contradiction so that we can all fix it. Nobody is saying, "We don't have a problem." Nobody is saying that "9/11 didn't happen." What they're saying is, "We're not a fragile country. Trust us to have this conversation, so that we can do this in the right way, in a more effective way."

Why is the country not having this conversation, the kind of conversation that requires the politicians who are responsible for the war to be specific to the concerns of the American people?

Because I don't think politics is any longer about a conversation with the country. It's about figuring out how to get to do what you want. The best way to sell the product that you want to put out there. It's sort of like dishwashing soap, you know, they want to make a big splash, so they decide to have more lemon, as though people are going to be like, "That has been the problem with my dishes! Not enough lemon scent!"

There seems a detachment emotionally and politically in this country from what is happening.

It's very hard to feel the difficulties that the military goes through. It's very hard to feel the difficulties of military families, unless you're in that environment. And sometimes you have to force yourself to try and put yourself in other people's shoes and environment to get the sense of that. One of the things that I think government counts on is that people are busy. And it's very difficult to mobilize a busy and relatively affluent country, unless it's over really crucial -- you know, foundational issues, that come, sort of, as a tipping point.

"War? What war?"

War hasn't affected us here in the way that you would imagine a five-year war would affect a country. Here's the disconnect: that the president says that we are in the fight for a way of life. This is the greatest battle of our generation, and of the generations to come. Iraq has to be won, or our way of life ends, and our children and our children's children all suffer. So what I'm going to do is send 10,000 more troops to Baghdad.

So there's a disconnect there. You're telling me this is the fight of our generation, and you're going to increase troops by 10 percent. And that's going to do it? I'm sure what he would like to do is send 400,000 more troops there, but he can't, because he doesn't have them. And the way to get that would be to institute a draft. And the minute you do that, suddenly the country's not so damn busy anymore. And then they really fight back, then the whole thing falls apart. So they have a really delicate balance to walk between keeping us relatively fearful, but not so fearful that we stop what we're doing and really examine how it is that they've been waging this.

But you were thinking this before you got McCain.

Sure, yes, this happened with McCain because he was unfortunate enough to walk into the studio. The frustration of our show is that we're very much outside any parameters of the media or the government. We don't have access to these people. We don't go to dinners. We don't have cocktail parties. You've seen what happens when one of us ends up at the White House Correspondents' Dinner; it doesn't end well. So he was the unlucky recipient of pent-up frustration.

You know, the media's been playing this big. CNN, USA Today ...

Well, they've got 24 hours to fill. You know, how many times can Anna Nicole Smith's baby get a new father?

But what does it say about the press that the interview you did became news? And, in a way, reflected on the failure of the "professional" journalists to ask those kinds of questions?

I don't know if it really reflects on the failure of them to ask. I think, first of all, for some reason, everything that we do or Stephen does -- Stephen Colbert -- is also then turned into news. The machine is about reporting the news, and then reporting the news about the news, and then having those moments where they sit around and go, "Are we reporting the news correctly? I think we are." And then they go, and the cycle just sort of continues. I don't know that there was anything particularly astonishing about the conversation, in that regard.

Have you lost your innocence?

What? Well, it was in 1981, it was at a frat party ... oh, I'm sorry ... You know, I think this is gonna sound incredibly pat, but I think you lose your innocence when you have kids, because the world suddenly becomes a much more dangerous place. There are two things that happen. You recognize how fragile individuals are, and you recognize the strength of the general overall group, but you don't care anymore. You're just fighting for the one thing. And then you also recognize that everybody is also somebody's child. It's tumultuous.

Your children are how old?

Two and a half and 14 months.

So, has it been within that period of time that you made this transformation from the stand-up comic to a serious social and political critic?

I don't consider myself a serious and social political critic.

But I do. And I'm your audience.

I guess I don't spend any time thinking about what I am, or about what we do means. I spend my time doing it. I focus on the task and try and do it as best we can. And we're constantly evolving it, because it's my way of trying to make sense of all these ambivalent feelings I have.

I watched the interview you did with the former Iraqi official, Ali Allawi. And I was struck that you were doing this soon after the massacre at Virginia Tech. It wasn't your usual "Daily Show" banter. I said, "Something's going on with Stewart there." What was it?

Well, first of all, you know the process by which we put the show together is always going to be affected by the climate that we live in. And there was a pall cast over the country. But also you're fighting your own sadness during the day. We feel no obligation to follow the news cycle. In other words, I felt no obligation to cover this story in any way, because we're not, like I said, we're not journalists. And at that point, there's nothing sort of funny or absurd to say about it. But there is a sadness that you can't escape, just within yourself. And I'm also interviewing a guy who's just written a book about his experience living in Iraq, faced with the type of violence that we're talking about on an unimaginable scale. And I think that the combination of that is very hard to shake.

And I know that my job is to shake it, and to perform. It wouldn't be a very interesting show if I just came out one day and said, "I'm going to sit here in a ball and rock back and forth. And won't you join me for a half-hour of sadness?"

But that wasn't performance when you were wrestling with the sadness you were feeling with him.

Well, I thought it was relevant to the conversation. I was obviously following the Internet headlines all day. And there was this enormous amount of space and coverage given to Virginia Tech, as there should have been. And I happened to catch sort of a headline lower down, which was "Two Hundred People Killed in Four Bomb Attacks in Iraq." And I think my focus was on what was happening here versus sort of this peripheral vision thing that caught my eye. I felt guilty.

Guilty?

For not having the empathy for their suffering on a daily basis that I feel sometimes that I should.

Do you ever think that perhaps what I do in reporting documentaries about reality and what you do in poking some fun and putting some humor around the horrors of the world feed into the sense of helplessness of people?

No. I mean, again, I don't know, because I don't know how people feel. And you know, the beauty of TV is, they can see us, but we can't see them. I think that if we do anything in a positive sense for the world, it's to provide one little bit of context that's very specifically focused, and hopefully people can add it to their entire puzzle to give them a larger picture of what it is that they see. But I don't think it's a feeling of hopelessness that people feel. If they're feeling what we're feeling, it's that this is how we fight back. And I feel like the only thing that I can do, and I've been fired from enough jobs that I'm pretty confident in saying this, the only thing that I can do, even a little bit better than most people, is create that sort of context with humor. And that's my way of not being helpless and not being hopeless.

Is Washington a better source for jokes now that the Democrats are in the majority?

It's more fun for us, because we're tired of the same deconstructed game.

Yeah, I saw that piece you did on the Democrats debating how to lose the war.

Right, exactly. This has been six years, you know; we're worn down. And I look forward to a new game to play, something new. I mean, the only joy I've had in that time is having Stephen's show come on the air and sort of give us a different perspective. And, you know, because it's made of the same kind of genetic material as our show. It feels like it's also freshened up our perspective and kind of completed our thought.

You could take me on as a correspondent.

We would love to take you on as a correspondent. You know, the pay is pretty bad.

Yeah, well, this is PBS. What would my assignment be? Would you want me to be your senior elderly correspondent?

I would like you to just sit in my office, and when I walk in, just lower your head and go, "That was ugly."

This excerpt originally appeared in "Bill Moyers Journal: The Conversation Continues" Copyright © 2011 Bill Moyers Published by The New Press, Inc. www.thenewpress.com Reprinted here with permission.

Bill Moyers was a founding organizer of the Peace Corps, a senior White House assistant and press secretary to President Lyndon Johnson from 1963 until 1967, the publisher of Newsday, a senior news analyst for CBS News and the producer of groundbreaking series for public television. He is the winner of more than 30 Emmy awards and nine Peabody awards. "Bill Moyers Journal: The Conversation Continues" is a new collection of some of the most memorable interviews from his PBS show.

Shares