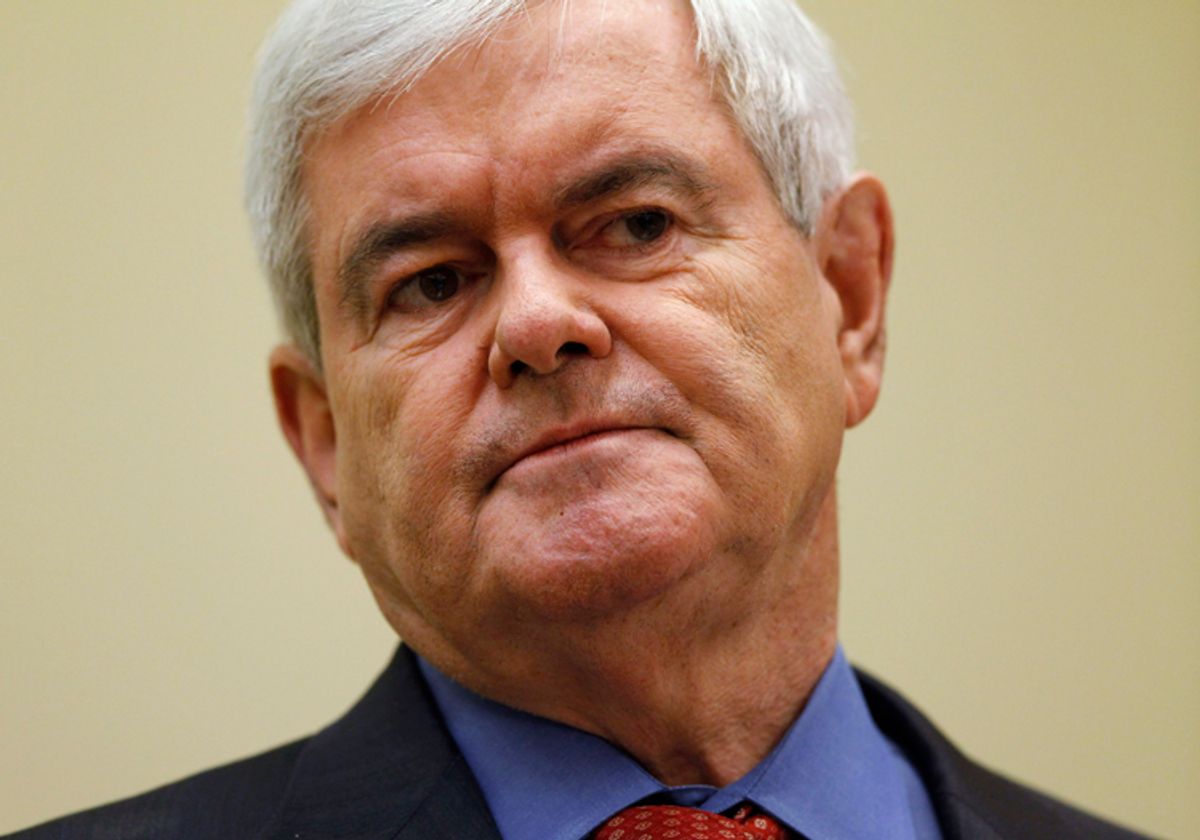

If his goal when he officially launched his presidential candidacy last month was to inflict a massive amount of humiliation on himself in as short a time as possible, then Newt Gingrich has succeeded spectacularly.

After an epically botched campaign roll-out -- which included accusations of ideological treason from influential conservatives and a nationally televised exchange with an Iowa voter who called him "an embarrassment to our party" and urged him to quit the race "before you make a bigger fool of yourself" -- Gingrich was left struggling to explain how he and his wife racked up hundreds of thousands of dollars in charges at Tiffany's jewelers. Then he randomly took off on a vacation (a lavish Greek cruise, it turned out), and now he's returned to find that virtually his entire staff has quit.

Does this latest development change the presidential race in any significant way? Not really. Since even before his month from hell, Gingrich had no realistic chance of winning the GOP nomination, and not since the 1990s has he been a significant force on the right. Most conservative activists and opinion-shapers long ago tuned him out.

But much of the political media world never quite figured this out, instead treating Gingrich for the last decade as an enduring relevant national leader. The instinct was understandable: The celebrity (and notoriety) he attained during his mid-'90s stint as House Speaker never fully faded, and he could always be counted on for a lively, provocative quote or two.

This is the promise of Gingrich's amazing crash-and-burn as a White House candidate (I know, he says he's staying in despite the staff defections): that it might compel the political media to realize that the emperor has no clothes.

The reality is that Gingrich's serious career in elected politics lasted for 20 years and ended in 1998.

He spent the first 16 of those years clawing his way through his party's House ranks, finally reaching the top spot just as the ideal circumstances -- complete Democratic control of Washington for the first time since the Carter administration, a profoundly unpopular president, and a ton of low-hanging fruit in the South -- presented themselves for a Republican takeover of the House. The midterm election of 1994 made Gingrich Speaker of the House.

The tactics he employed during that rise could be devious. Early on, he formed the Conservative Opportunity Society with about a dozen fellow far-right GOP members. They pushed their party's leadership toward a more confrontational posture and engaged in harsh and highly personal attacks on their Democratic colleagues.

In one episode in 1984, Gingrich used an after-hours "special orders" speech on the House floor to read off the names of ten Democrats who had written a letter to Daniel Ortega, whose Sandinistas had seized control of the country in 1979, urging him to hold democratic elections and to allow expatriates to return to vote. The ten, Gingrich said, had "undercut and crippled" U.S. foreign policy; he suggested they be prosecuted under the Logan Act of 1798, which gives the president the right to conduct foreign policy. Upon learning of this, Speaker Tip O'Neill confronted Gingrich on the floor, calling his attack "the lowest thing I've seen in my 32 years in Congress."

In 1989, Gingrich edged out Edward Madigan, the candidate preferred by Robert Michel, the pragmatic House GOP leader, to become minority whip, then the No. 2 position on the Republican side. Four years later, in the run-up to the 1994 election, Michel announced that he'd retire. Officially, it was his decision, but Gingrich was breathing down his neck. The GOP conference was increasingly filled with confrontational conservatives who preferred Gingrich's style.

His four-year run as Speaker proved disastrous, for Gingrich personally and for his party. His own obnoxious style -- when a South Carolina woman drowned her children in a horrifying late 1994 incident, Gingrich called it a sign of society's breakdown and proof that people needed to vote Republican -- alienated all but the most hardcore Republicans. And his eagerness to force a government shutdown over a GOP plan to slash Medicare spending gave President Clinton and Democrats a winning issue in 1996, when nearly 20 Republican incumbents lost their seats and the GOP barely held the House. Shortly after that, Gingrich held off an attempted coup from a band of frustrated but incompetent House Republicans. Then he made things worse for his party by leading an impeachment drive against Clinton in 1998 (even, as we later learned, while engaging in an extramarital affair himself), which backfired and led to shocking Democratic gains in that year's midterms.

It was then that Gingrich took his massive unpopularity and walked off the political stage, knowing that his party was ready to throw him off if he didn't make the first move. From that moment on, the party's elites -- elected officials, activists, interest group leaders, and opinion-shaping commentators -- have had little use for him. But the media has been a different story. A few years after his demise as Speaker, Gingrich reemerged and was quickly welcomed back into every green room in America. Convinced he'd been rehabilitated, he began making noise about seeking the presidency, first in the run-up to the 2008 race and then again this time. His taste for ugly, personalized attacks hadn't faded, either, something he's shown over and over during the Obama presidency.

But the idea that he was a real player in politics was an illusion, something that's become clear during the month-long Gingrich candidacy. Most of the important figures in the Republican Party never had any interest in seeing him run for president. There have been few endorsements, donors have shunned him, and conservative activists and commentators have amplified every one of his embarrassments.

Even with his staff quitting on him, Gingrich insists he'll stay in the race. We'll see how long that lasts. One way or the other, he'll soon be taking the same walk of shame off the political stage that he took 13 years ago. This time, let's hope it's for good.

Shares