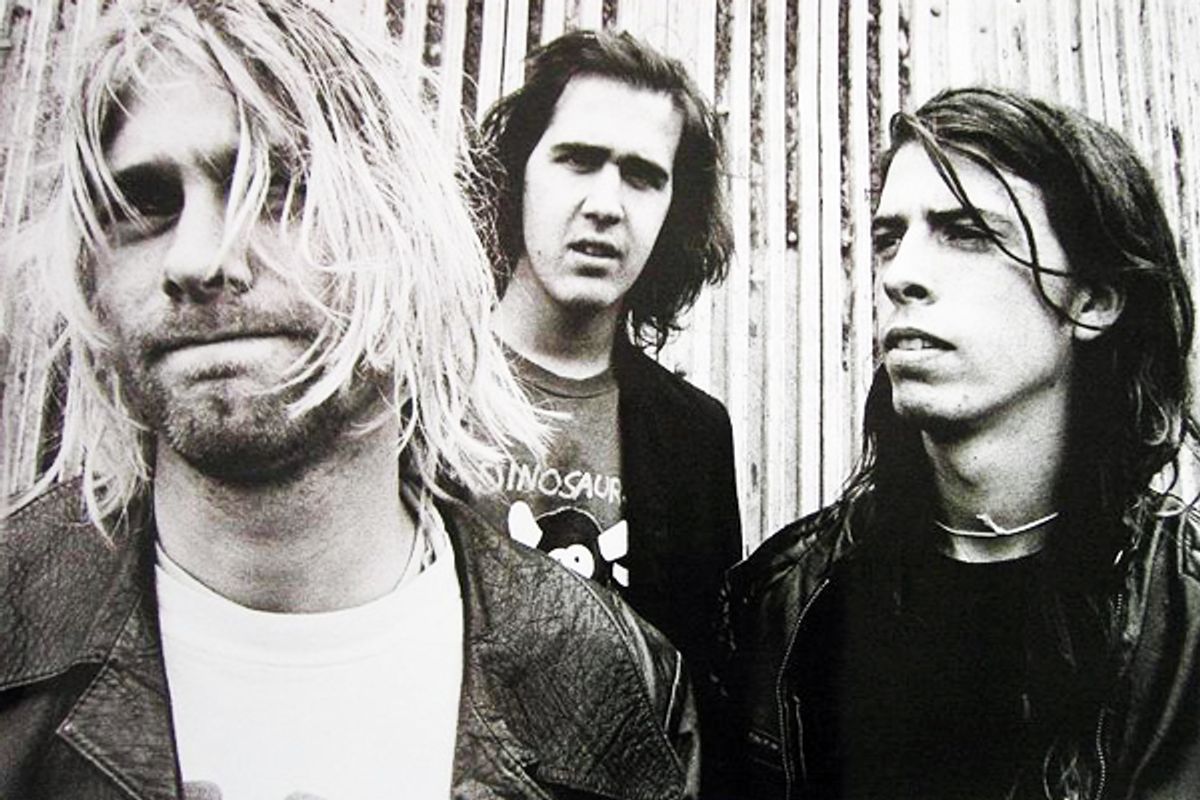

Twenty years ago today, the now-legendary Nirvana released "Nevermind," the album that exploded the band's glorious, grungy fusion of punk, pop and heavy metal out of the Seattle underground into popular consciousness. Three quick years later, frontman Kurt Cobain's suicide provoked a cascade of overblown eulogies, many proclaiming the troubled musician something along the lines of Newsweek's tribute: "the authentic voice of the 20-plus generation."p>

Much as Bob Dylan disavowed any label as voice of the 1960s generation, Cobain resisted claims to the epochal significance of his songs. Cultural expressions like Nirvana's seminal "Smells Like Teen Spirit" tend to contain discrete nuggets of truth about a particular moment rather than to encompass the totality of experience for an entire age cohort. Now, at the telltale 20-year mark, it's more necessary than ever to pierce through the media-driven platitudes about Nirvana emerging fully formed overnight to transform music and the music industry.

Nirvana was not simply a desperately needed blast of fresh air, clearing out exemplars of musical artifice ranging from Milli Vanilli to the legions of 1980s hair-metal bands. And the band did not come from nowhere -- and happily proclaimed its debt to bands like the Pixies and Husker Du to anyone who would listen. Cobain even had a tattoo of the logo for K Records, the Olympia, Wash., label run by Beat Happening's Calvin Johnson.

Indeed, for more than a decade before "Nevermind," marginally commercial, independently produced music bubbled with creative ferment. It germinated underground, scene by scene, far from the MTV music videos that were the 1980s mainstream's signature cultural product. Nirvana blossomed from a vast network of subterranean roots. In hundreds of dive bars and clubs, scores of local independent record stores, and dozens of dedicated fanzines, musicians honed an authentic sound drawn from diverse and often whimsical influences, and communities of fans created a distinct shared identity.

The Nevermind tour opened in small clubs like the 9:30 Club in Washington, D.C., Cat's Cradle in Chapel Hill, N.C., and Liberty Lunch in Austin, Texas -- a well-established circuit devoted to innovative, risk-taking, authentically expressive music more than slick corporate entities systematically engineered to separate late teens and 20-somethings from the meager spoils of their uninspiring day jobs. The music was less about seminal 1970s punk acts like the Ramones or the Sex Pistols than it was about keeping the flame of edgy attitudes and sensibilities alive, as the music blossomed in a hundred different directions throughout the Reagan-Bush era.

Stylistically, these directions ranged from the minimalism of hardcore's Black Flag to the atonal avant-garde-inspired dissonance of Sonic Youth; from the "econo" conceptualism of the Minutemen to the Pixies' demonically twisted rants with catchy hooks and the multi-faceted brilliance of Husker Du. Even bands that ultimately enjoyed obvious commercial success, notables like R.E.M. and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, toiled early in their careers on this same circuit, patronized by many of the same fans.

While most of what got played on "college radio" was more about personal angst than politics, parts of this subculture still voiced opposition to the era's dominant cultural and political life -- militarism, social conservatism, rampant materialism and the veneration of corporate America. Independent label SST Records adopted "Corporate Rock Still Sucks" as its slogan, and Cobain epitomized the community's ambivalence towards the era's aggressive commercialism when he famously appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone sporting a "Corporate Magazines Still Suck" T-shirt. The photograph also highlighted the ironies of making commercially distributed music with an anti-establishment outlook. "Smells Like Teen Spirit" encapsulated this in its sardonic lyrics ("here we are now entertain us,") in the snarl of Cobain's vocal delivery and in the buzz-saw distortion of its infectious guitar riff.

Though "Smells Like Teen Spirit" compelled a wider circle of fans to listen, this does not necessarily add up to the "voice of a generation" mantle the popular media fastened on Cobain. It's more accurate to see his celebrity as an uncanny symbol of a vibrant minority of the era's young who considered themselves outside the mainstream. Cobain's discomfort with fame, commercialism and the material rewards they carried were symptomatic of currents that ran deeper throughout this subculture.

Long before "grunge" became a household word, spawning its own fashion trend complete with wispy models flaunting designer lumberjack shirts on runways, a palpable rebelliousness and nonconformity energized post-punk fans and performers. Cobain would not have sprung, seemingly overnight, with a sonic vengeance from the Seattle drizzle to superstardom without tapping into this ethic and personifying it. Remarkably, he and his band continue to exert a magnetic influence on a new generation of would-be rock heroes in an era where the roadmap to Nirvana-like success is unclear given the music industry's transformation in the iPod age. Nirvana's staying power testifies to its enduring appeal to those longing for music with an authentic spirit of resistance and yearning for a community that embodies that spirit.

Shares