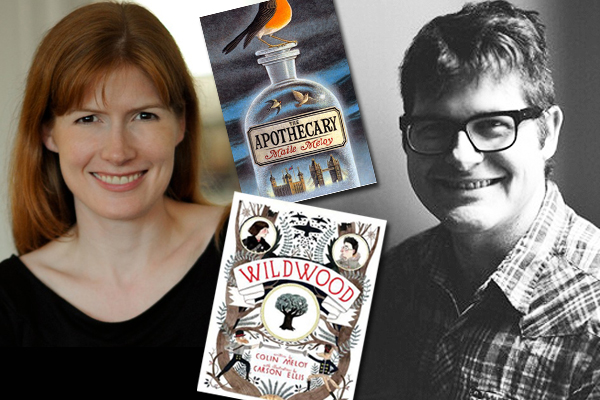

Are there two other siblings in the midst of such a wildly imaginative run as Maile and Colin Meloy? Maile Meloy is one of the most acclaimed writers of her generation, a terrific storyteller with boundless range, nary a word out of place, and a genius eye for the smallest details. Colin Meloy fronts the Decemberists, the arty Portland, Ore., alt-rock collective whose catalog includes wild concept albums, 18-minute songs based on Irish myths, sea shanties and perfect, concise pop songs. Oh, and he piloted the band to the top of the Billboard album charts this year with “The King Is Dead.”

Now both Meloys have new young-adult novels in stores. Colin’s adventure-fantasy, “Wildwood,” is a collaboration with his wife, illustrator Carson Ellis, and the first of a planned trilogy. As the New York Times notes, it “brims with grimly comic violence. Coyotes dressed in Napoleonic uniforms train musket, cannon and bayonet on woodland bandits, talking birds and an industrious rat named Septimus.” Maile, meanwhile, steps away from her realist adult fiction with a fantasy of her own, “The Apothecary,” brimming with teenage spies, Cold War fears, magical elixirs and thrilling first kisses.

How did these two boundless imaginations get their start? We asked the Meloys to discuss their childhood in Montana, where they found early inspiration, and how two delightful yet distinctive storytellers emerged from one family.

Maile: We grew up in Helena, Mont., and there was a lot of freedom to run around by ourselves. We lived for a while on a hill, and down the side of the hill there were caves, which might have been old half-completed mining shafts. Sometimes you’d find a rusty tin can in one, and I imagined that old prospectors had left it, although it had probably been recent hobos.

Colin: My friend Mark and I named all those caves. I think we called one “Sleeping Cave” because we found a little assembled hobo bedroom in the back of one, mattress and all.

Maile: Yikes.

Colin: But yeah, there was plenty of open space to roam around in. Mom didn’t have a TV (we had to borrow the neighbor’s black-and-white set to watch the pilot episode of “V”) but Dad did.

Maile: But we couldn’t get any network channels at his house, so we got early HBO.

Colin: And we couldn’t watch TV during the day; on weekends we were practically forced outside. So a lot of my early imaginative play I think drew from that: having to find creative ways to entertain myself that didn’t involve being inside or watching TV. But after the sun went down, all bets were off. I distinctly remember Dad letting us watch “The Shining.” It was at the Rodney house so I must’ve been, what, 6?

MAILE: That would have made me 8 or 9. That seems about right. I remember seeing the poster first, at the Second Story Cinema, which was the art-house movie theater in Helena, and our dad saying, “That’s a really scary movie.” And then I remember sitting in our living room watching Scatman Crothers walk through the lobby of the hotel — oh, God. It still scares me.

Colin: I think there was a weird level of trust given us by our parents and the greater adult world. An understanding that we wouldn’t grow up to be creeps.

Maile: We had a great kindergarten teacher who built, under Colin’s guidance, a Millennium Falcon in a sort of fort space in the classroom, with knobs and dials inside for flying it. Colin, how did that come about?

Colin: Yeah, Mr. Wolf. For whatever reason, I must’ve distinguished myself from my fellow “Star Wars” nerds and I was his consultant on that project. Me and Josh Maureen. And it seemed like the construction took forever, but when it was opened, Mr. Wolf promised that Josh and I would be the first to play inside of it. It had spinning dials made from spent Super 8 reels and lights that lit up when you flipped a switch and a pair of really cool old fighter-jet helmets. The day of the big unveiling, I got so sick with the flu that I had to stay home from school. I was so devastated. My friend Mark got to go in my stead.

I think we were allowed a lot of leeway and responsibility as kids from the adult world. Maile, didn’t you walk to school your first day of kindergarten? Or was that a staged photo, the one of you starting the walk down the hill all by yourself?

Maile: I don’t know if it was staged or not, but I do remember walking to school by myself. I just don’t know how I would have done it on the very first day. It was a mile, and I was 5. I guess 5-year-olds have done harder things.

Colin: I’ve seen some of the old home movies and I can’t believe how many of them involve shots of us doing some fairly dangerous activity, like walking on ice or climbing on a bunch of rocks, without an adult in sight.

Maile: I definitely had the sense that we could do things on our own. In the one of me walking on the ice, the third time I wipe out, I’m better at standing up again.

Colin: Seems like that attitude might also be attributed to the general vibe of the ’70s/early ’80s. Fairly hands-off, it seems to me. And nowhere was that more true than Montana — a state that has a real tolerant streak to it. I think our family also gave us the impression that if we wanted to do something, then there wasn’t any reason we couldn’t. I don’t think I thought that was an unusual atmosphere ’til I got older and met people who might’ve been more constrained in their upbringing.

Maile: I always had the sense that art was important. It was a thing you were supposed to do as a normal part of life, just not necessarily as a career.

Colin: Yeah, that was the big caveat. While there was never a suggestion that, for example, Maile and I were expected to take up where my dad and my grandfather left off and join a law firm — that sort of thing. It really did feel like we were allowed to pursue whatever we wanted to — and I think our creative streaks were really encouraged. However: Dad made it very clear that we should not pursue a creative life as a career. It should always be something you do on the side.

Maile: Our grandfather’s brother, Hank, was a painter who died young while teaching art at Columbia and living in a cold-water walk-up. It was devastating to our grandfather. I remember hearing the story of his getting the telegram and leaving a dinner party in silence. I sort of wonder if Hank’s story was a kind of object lesson, if his death made it seem dangerous to try to make a living as an artist.

Colin: I don’t remember people talking about Hank as a cautionary tale; I might’ve missed that bit. I was always very much in awe of Hank’s life. It seemed to me like he was the real hero of the family; the guy who, with his own creative work, managed to get out of Montana and become a professional artist! We never met him, but he loomed large in the family like a ghost.

Maile: It helped that he was insanely good-looking.

Colin: And neither of us followed our dad’s advice, that’s the funny bit. I made quite a lot of hay out of it early on with the Decemberists — the old songs are peppered with all sorts of “ha, I showed you, Dad!” bits. I had a real chip on my shoulder, then. Maile, not so much, right?

Maile: I was too busy trying to figure out what I was doing to have a chip on my shoulder.

Colin: But I don’t blame him; I think my career is largely a fluke. I think his advice is actually pretty solid. But I do like to think that there’s a kind of hidden footnote to that mantra, one that he couldn’t have mentioned without totally undercutting himself: That if you really think you can do it, then you should just go for it.