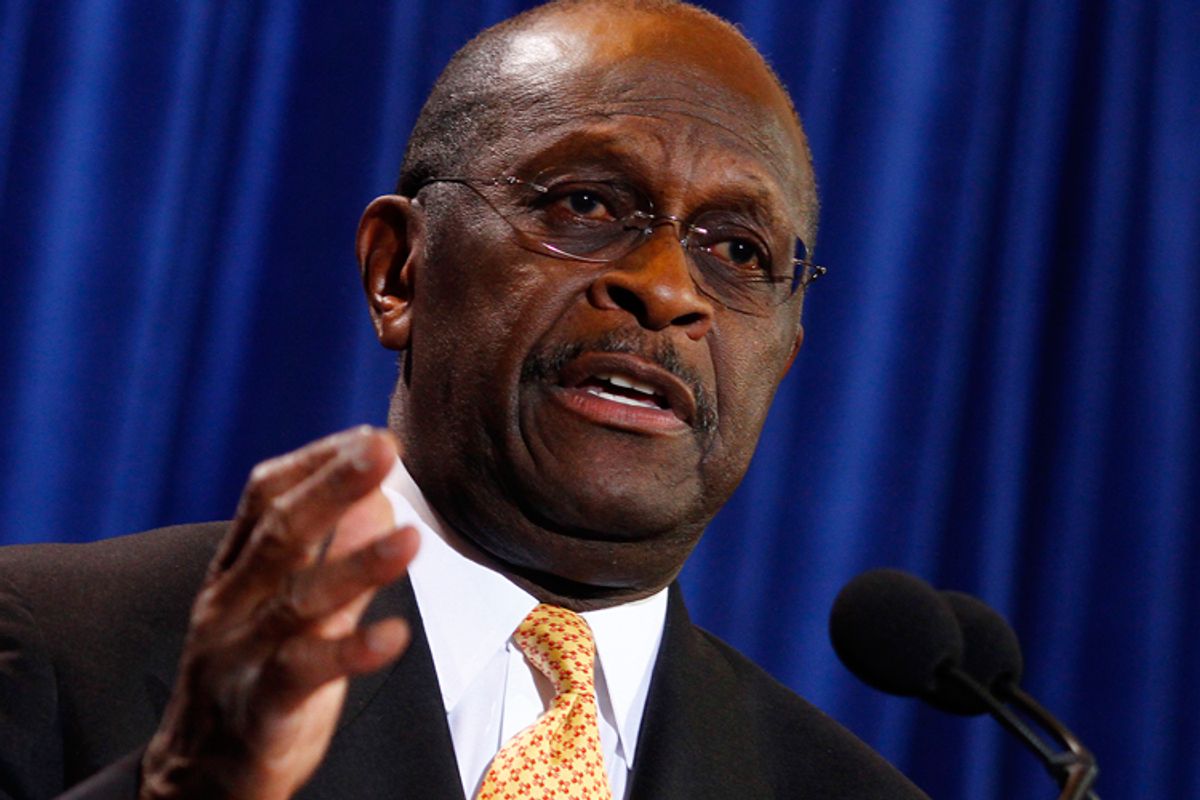

The sexual harassment and assault accusations against Herman Cain raise an issue often in the news these days: the propriety of confidential agreements. From the facts the public knows, the National Restaurant Association, when it was run by Cain in the 1990s, entered into confidentiality agreements with several female employees who claimed he groped them and were paid to keep quiet about it. Confidentiality agreements have also figured in the controversy over the Catholic Church's long-standing practices of requiring confidentiality agreements when paying lay complainants for their claims against predatory priests.

Are confidentiality agreements a good thing? They certainly encourage settlement. Most civil litigation, over 95 percent by most reliable estimates, concludes in a settlement. The risks, stress and costs of litigation encourage settling cases. The courts also encourage settlements as measures for judicial economy. And most settlements – in and out of courts – end with confidentiality clauses, which the parties sign, agreeing to keep the charges and settlements confidential. The motive for the defendant is to pay a price to keep a contested charge private, whether or not it is true. Cynics call that practice extortion; realists call it the price of doing business.

But should it be? And when such a deal is done, should the confidentiality ever be breached?

The facts of Cain's situation are not yet entirely clear. From what has been credibly reported is that the Restaurant Association paid several employees who claimed Cain sexually harassed them. One of these cases reportedly involved litigation; all were settled privately. The complaining women employees agreed to keep their complaints confidential.

But after Politico reported the existence of the agreements, an attorney for one of the employees reported the anonymous charges of his client, embarrassing Cain and possibly derailing his campaign. The public does not know whether the Cain cases were examples of nasty incidents that were covered up, or were exaggerated claims kept quiet because they weren’t worth the battle, or something in between.

The leak of that information was, in my view, unethical. Individuals have a fundamental right of contract, and the women who made these deals took the money, promising to be quiet, then hurt the person whose silence the association thought it had bought. One can't have it both ways. Either make the claim public, or take the money to be quiet. You can't have both. A deal is a deal.

The fourth woman, Sharon Bialek, who just came forward, did not sign any confidentiality agreement, and she had every right to make her complaint public –- tardy as it was. Her claim has credence on its merits partly because it follows the revelations of the others, which compounds the question about the broken agreements of the others.

If Herman Cain were not a public figure running for the Republican Party's presidential nomination, he would have every right to sue any woman who violated the confidentiality agreement whether through surrogates, or themselves. The law holds that contracted conditions of confidentiality are enforceable, and violations should be compensated. Breach of confidentiality in settlement agreements is generally viewed as a breach of contract and remedied in state court. Depending on the state, the usual remedies are damages, injunction, and specific performance. Courts rarely enforce monetary damages as they are harder to prove, but many settlements have liquidated damage clauses, which courts will enforce if they were entered into freely and voluntarily.

As a practical matter, Cain cannot sue them, however wronged he may be.

The larger question

The Catholic Church cases raise the same issue: that is, should courts allow confidentiality agreements when there is a public interest in knowing the information muzzled by these agreements.

In the case of the church, I would say, no, the courts should not permit confidential settlements that shield misconduct that could be repeated. For example, where a faulty car or toxic drug or dangerous structure is concerned, and might hurt others similarly situated, confidential agreements should not be sanctioned by courts. That was the situation with the cases that eventually bankrupted Catholic dioceses in the U.S. and abroad because it was shown that the church as an institution knew about the predatory priests, kept their misconduct quiet, and permitted them to repeat their misconduct.

Some may argue that the Cain situation is comparable to the Catholic Church cases, that sexual harassment, like faulty cars and toxic drugs, is a matter of public policy, that a systemic wrong is under consideration and the defendant should be outed to prevent future misconduct. Opening up the confidentiality agreement, in this line of reasoning, would prevent other similar offenses.

Following that logic, however, any defendant could be deemed a potential repeat offender in every disputed claim, and thus no confidentiality agreements should be permitted. That could be construed as violating people's right of contract. Most courts would be against it, because it would force most disputes to go to trials.

If the question came before a court now, as a matter of pure law, not politics, I would expect that the Cain confidentiality agreements would be upheld. Only one incident gave rise to a legal complaint in a court case, as I understand, and the complaint was individualized, not systemic on its face.

The others complaints were addressed administratively within the Restaurant Association, as private, contractual matters. Challenging the right to open the confidential agreements years later would not be bullying the women into silence, it would be holding them to contracts they and their lawyers agreed to and were paid for.

Cain isn't the issue

There is an important point to be made, one that goes beyond Cain and the Catholic Church. Cain's complaint that the press manufactured the scandal is naive; revealing stories is what the press does. His complaint that the charges are politically motivated also is naive. The timing suggests that there is a political motive, by the complainants and by his competitors in the primaries, but that is what political campaigns are about.

The point I make here is that private agreements should be honored by the parties. Just about every doctor, lawyer and businessman has settled a charge that he genuinely denied because it was not worth the time and public insult to publicly defend against the claim. Pay the money, bury the charge and move on, holding your nose, is a very common practice. Michael Jackson fans thought he was betrayed when a civil settlement was leaked during a later trial, because he claimed he only agreed to the payoff to avoid negative publicity. Secrecy lubricates dispute resolution.

Whether Cain was guilty of the claims against him or innocent, any of the women who made their claims and took the money, agreeing not to make the claims public, should not have broken their commitment years later. As a matter of policy, that is not proper conduct, whatever one thinks about Herman Cain.

When to keep secrets and when to require openness is a fundamental question our society is continuously balancing. On my scale, institutional issues like those raised by the Catholic Church cases should be open, and private matters like the Restaurant Association’s should remain private.

Shares