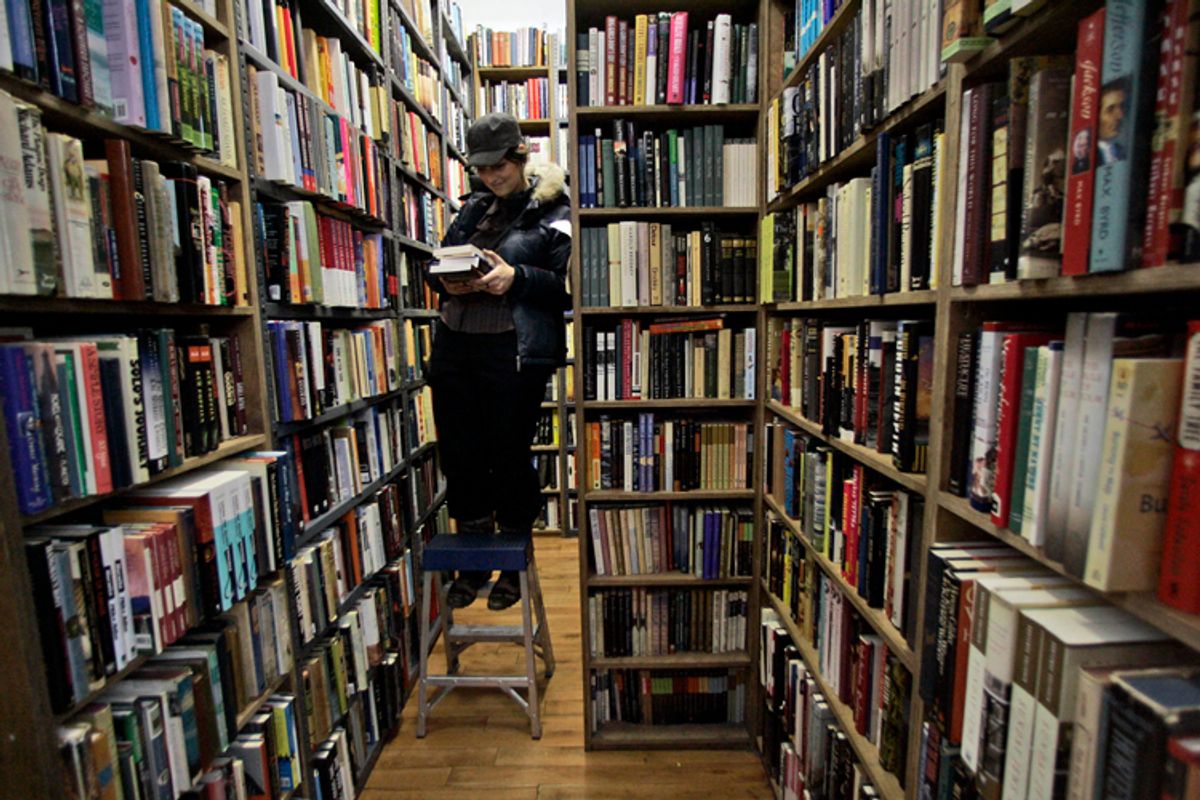

On a recent evening in Washington, D.C., Kramerbooks was hopping. Getting inside meant actually shimmying past people who were chatting and poring over the stacks. There's a restaurant in the back, but on this particular night there was no wait for a table, so it's safe to say that the vast majority of these people were using Kramerbooks as a place to hang out.

Two doors down, at Beadazzled, a bead and jewelry shop, no such crowd could be found. Both stores are independently owned, well-liked local institutions that have been in D.C. for decades. But Kramerbooks is a hive of ebullient chatter on any given night and Beadazzled isn't. Why do bookstores so often become magnets for bustling urban activity?

Bookstores enjoy a rare trait: To many, the store itself is seen as at least as important to the community as the product it sells. There are several reasons for this, which is why a Slate story published earlier this week called "Don't Support Your Local Bookseller" has sparked a small online uprising of indignant bookworms. In the story -- so paint-by-numbers counterintuitive that it almost reads as a parody of a Slate piece -- Farhad Manjoo argued that people should buy books on Amazon and let independent bookshops wither. "Buying books on Amazon is better for authors, better for the economy, and better for you," he writes.

Authors and economists can duke it out over the first two claims. But "better for you" is a lot of B.S. if you are lucky enough to live somewhere that has a quality independent bookstore. (And if you live in the suburbs, I bet it's hard to find a parking spot by your local Barnes & Noble on a Friday night, just as it was at Borders, before bad business decisions pushed it into bankruptcy.) Unlike almost any other kind of retail establishment, bookstores operate as quasi-public neighborhood trusts that give city dwellers more than they receive in return. Like art galleries, they're a free-of-charge indoor urban venue where you can make yourself comfortable without being expected to eat something, drink something, or even buy something.

This is why the most-loved bookstores tend to hang on: Kramerbooks and Politics & Prose in D.C., The Strand and McNally-Jackson in New York, Skylight and Book Soup in Los Angeles, Tattered Cover in Denver, Book People in Austin, Texas -- the list goes on. Their patrons are numerous enough that even if only a fraction of them make a purchase it adds up to a profit. That doesn't really make them like Whole Foods, as Manjoo suggests. Yes, both Whole Foods and independent bookstores provide a luxury shopping experience, but bookstores provide a cooperative aspect that goes well beyond that. No one goes to Whole Foods just to soak up the atmosphere -- everyone's ultimately there to buy quinoa and ramps. Bookstores, on the other hand, function as communal spaces, which makes them valuable urban amenities.

By the same token, bookstores are more similar to farmers' markets than Manjoo admits in his piece -- people feel strongly that they want farmers' markets in their neighborhoods, and they shop there to show that. If they just wanted fresh ingredients sustainably sourced from local farms, there are plenty of cheaper places to find those in most cities these days. Yet like bookstores, farmers' markets are packed with shoppers and gawkers alike. People go for the scene.

Like farmers' markets, bookstores are an example of what urbanists refer to as "third places" -- places that usually exist to sell something but that also contribute to a city's public realm, like coffee shops. "In this way, 'literary culture' may also translate to 'urban culture,' and the appreciation urban residents have for the inherent qualities of urban life," says Mike Lydon, principal of the Street Plans Collaborative, an urban planning firm. "One might describe Amazon as the fast, cheap, standard, virtual suburban big-box model, while the indie bookstore is the urbane alternative that is seemingly rising alongside the rediscovery of America's urban neighborhoods." He may be right: after a long decline, the number of independent bookstores stabilized in the last few years and has even ticked slightly upward, according to the American Booksellers Association.

Lydon points to Greenlight Bookstore in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, which was essentially funded through crowdsourced loans from people in the community who wanted a bookstore nearby. Locals loaned the prospective owners $70,000 in increments of as little as $1,000. "It was worth it not only because it helped us get the capital together, but because there are all these people who feel so invested in this store," co-owner Jessica Stockton Bagnulo told the press after Greenlight opened in 2009. "Literally, they own a piece of it."

All of which is to say, Manjoo's argument that bookstores don't really foster a local literary culture wildly misses the point. They foster a local culture, period. Bookstores provide a space to meet friends, cruise for a date, and hide out when you have nothing to do on a Saturday night. They provide a small slice of intellectual development in a retail landscape that's otherwise dominated by denim, cupcakes and facial moisturizer. And they do so without asking much in return -- just that we come in frequently, browse all we want, and occasionally buy a book at retail price. If people mythologize bookstores, that's the reason. Rather than look for reasons why they shouldn't be celebrated, you could just as easily ask why, even in the age of Amazon, they still are.

Shares