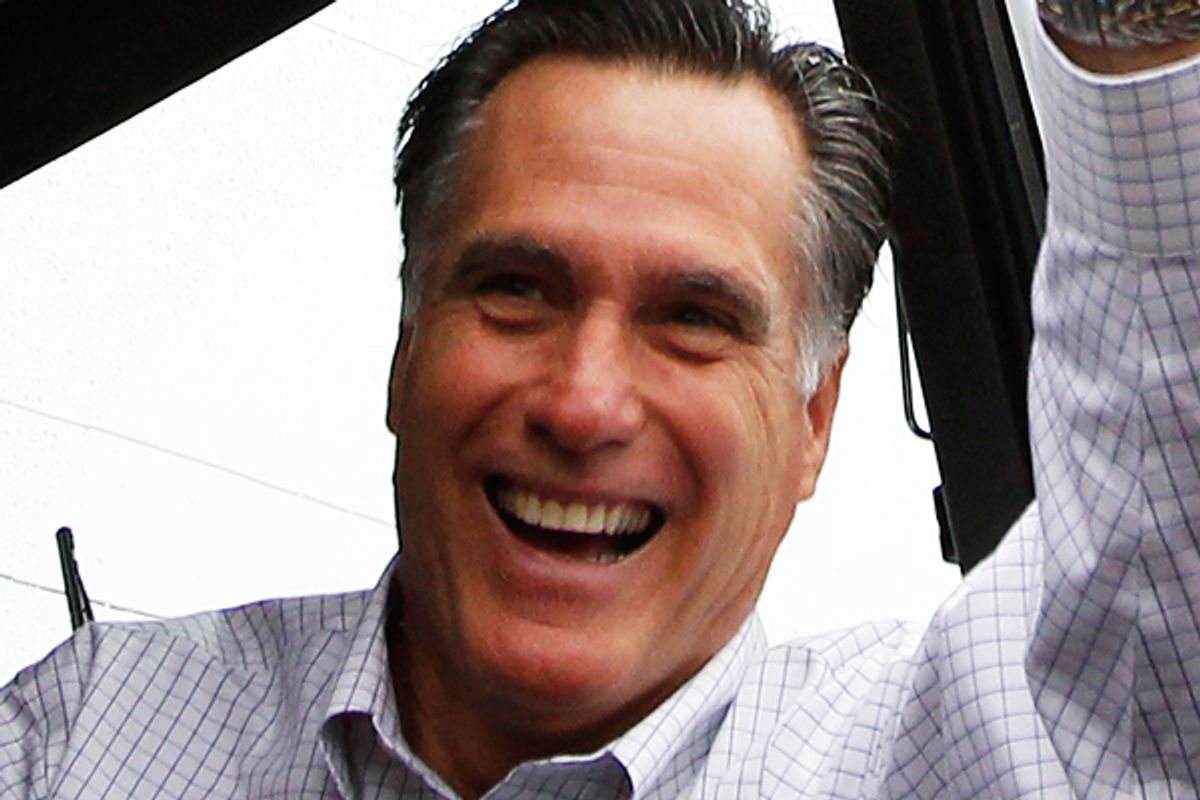

If Mitt Romney succeeds in becoming the Republican Party's presidential nominee, here's a question we're likely to hear a few times between now and November. How is it possible that one of the richest men in the United States paid an effective tax rate of only 13.9 percent on income of $21 million in 2010? The top income tax rate in the U.S. is 35 percent, supposedly applicable to any American who earns more than around $350,000 a year.

Technically, the answer is fairly straightforward. The vast majority of Romney's income isn't actually "earned," in the sense that wages or a salary is earned. His income is mostly derived by profit realized on the sale of investments. Such investments fall under the "capital gains" income tax category. The capital gains tax rate currently sits at 15 percent. (Any dividend income on his investments is also taxed at a 15 percent rate.)

The story gets a bit more complicated when one considers that a significant portion of Romney's income isn't derived from his own personal investments, but comes from his share of profits generated by Bain Capital, the private equity firm he used to run, from managing other people's money. In 2010, Romney earned $7.4 million from his legacy involvement in Bain. But thanks to an extremely-favorable-to-the-1-percent tax accounting quirk, Romney's share of those profits fall under the category "carried interest" -- and under current tax law, carried interest income is treated as capital gains.

There are other odds and ends. For example, Romney was probably able to avoid paying taxes on his speaking fees and book royalties ($528,871 in 2010) by offsetting it with contributions to charity and the Mormon church. But the unassailable point is that Romney was absolutely correct when he said in Monday night's debate in Florida that he paid exactly what he legally owed in taxes. By a strictly legal definition, Romney is not a tax cheat. In the United States, if your income is generated passively from investments, you pay a lower tax rate than if you work for a living.

The question of how that scenario came about is where the story gets a little bit more interesting.

Historically, the capital gains tax rate has bounced around quite a bit over the past 100 years. Just prior to the Great Depression, the maximum rate was only 12.5 percent. A post-Depression backlash against stock speculators hiked the rate up to around 25 percent. There it remained right up into the late 1960s, when it started rising sharply again, reaching a peak of 39 percent during the Carter administration.

Carter lowered the capital gains tax rate to 28 percent, and then in 1981, Reagan pushed it all the way down to 20 percent (at the time, the lowest mark since the Hoover administration). But as part of the landmark 1986 tax deal between Reagan and a Democratic Congress, the rate was raised back up to 28 percent.

And there it stayed put until the unholy alliance of Alan Greenspan, Bill Clinton and Newt Gingrich engineered another cut -- down to 20 percent -- as part of the 1997 budget deal that resulted in Bill Clinton's first balanced budget.

Alan Greenspan notoriously believed that the capital gains tax rate should be set to zero -- a policy that Newt Gingrich still supports. Interestingly, press reports at the time noted that most of Clinton's staff, including his then secretary of the treasury, Robert Rubin, and his chief of staff, Leon Panetta, opposed lowering the capital gains tax rate.

So if we're looking for someone to blame as a key driver of income inequality in the last 15 years, the Big Dog himself, Bill Clinton, should be our prime target. But George W. Bush also helped; he lowered the capital gains tax rate down to its current 15 percent as part of his 2003 round of tax cuts.

Barack Obama has, in the past, indicated muted support for raising the capital gains tax rate. If the Bush tax cuts expire, the rate will jump back up to 20 percent. A more sticky question is whether Congress will ever change the provision that treats "carried interest" as capital gains. The fact that carried interest is not treated as normal income is a result of court decisions and IRS rule-making rather than any specific law passed by Congress. But in recent years, as critics have argued that letting hedge fund and private equity managers treat the bulk of the profits they generate from managing other people's money as capital gains allows some of the very richest Americans to scoot out from under our supposedly progressive tax system, there have been some efforts to close the loophole. In 2009, the Democratically controlled House passed several bills that would have treated carried interest as normal income, but in the face of intense lobbying from private equity and hedge fund interests -- including Bain Capital -- the measures never made it through the House.

The release of Romney's tax returns, if nothing else, should reignite the political heat over carried interest, and our historically low capital gains tax rate. In an election year when income inequality is sure to be a major part of the narrative, Romney's tax returns are a windfall. Blame who you want -- Alan Greenspan, Bill Clinton, the courts, or a Congress supine before financial industry lobbyists -- but we owe a thank you to Mitt Romney. We've never gotten a clearer picture of the privileged position of the 1 percent than we do from the former governor's returns. No wonder he didn't want to release them.

Shares