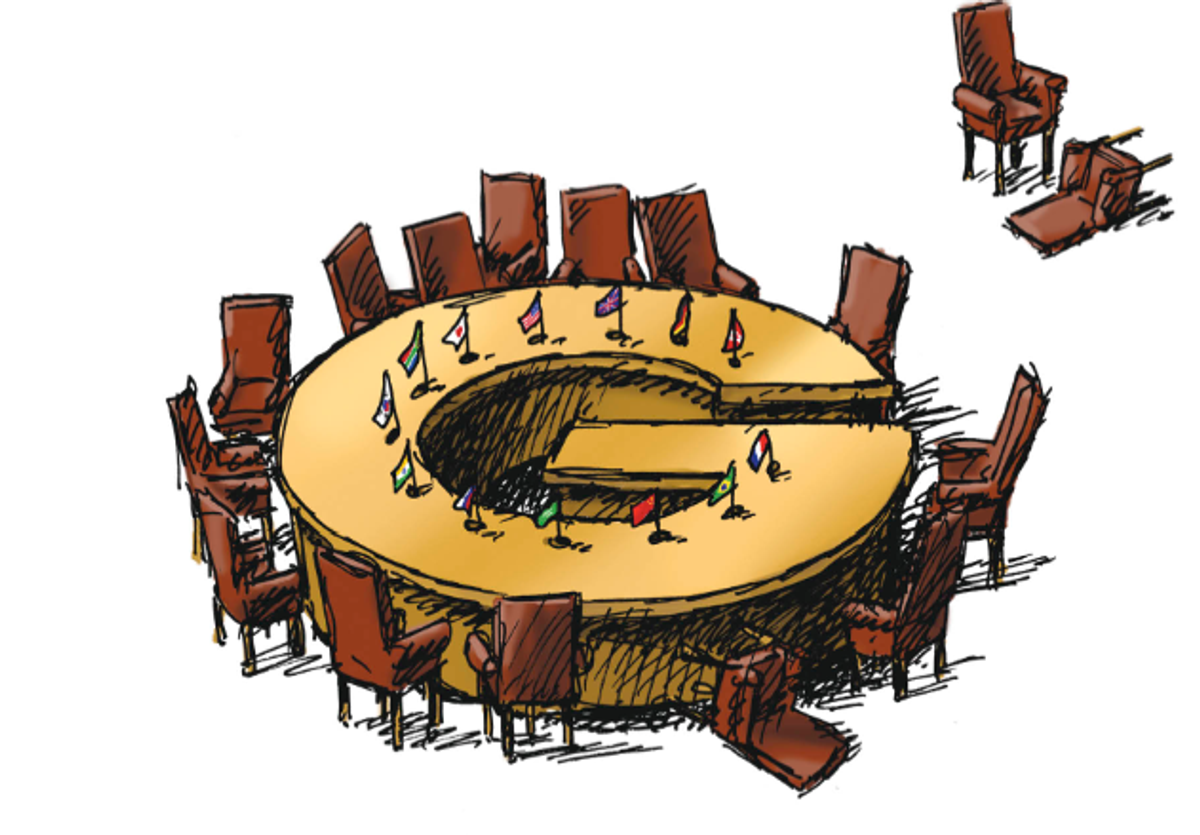

For the first time in nearly a century, the world doesn't have a clear set of leaders. A generation ago, the G-7 -- France, Germany, Italy, Japan, United Kingdom, United States and Canada -- not only powered the global economy, they also, for better or worse, made the decisions that determined the outcome of the entire world. But over the last several years, the dynamic has changed.

According to a widely discussed 2010 report by London's Standard Chartered Bank, the world has entered a new "'super-cycle" in which traditional economic hierarchies are being upended. Ever since the financial crisis, the U.S. has lost the economic strength and force of will to be the world's policeman. The number of Americans, for example, who believe the U.S. should "mind its own business internationally" has spiked to a level unseen since the 1950s. Meanwhile, new powers, like China, India and Brazil, have been unwilling to fill the power vacuum the U.S. has left behind. One could argue that this is a nice change from America's aggressive past interventionism, but it has also helped create the global stalemate on everything from global warming to humanitarianism in Syria. And it's a fact that has the potential to radically affect our future, both in positive and negative ways.

According to Ian Bremmer, the author of the new book "Every Nation for Itself," the rise of the "G-Zero" means the world has entered a transformative new phase -- which will be more chaotic, uncooperative and dangerous. In his book, he charts how America assumed the burden of global leadership in the wake of World War II, and how institutions like the United Nations, NATO, the G-7 and the IMF helped it dictate the international agenda for much of the past century. He also explains how the breakdown of those (often problematic) institutions is now hurting our ability to marshal global leaders to deal with some of the greatest threats facing our planet. Bremmer, the head of a global political risk research firm who has written for the Wall Street Journal, Newsweek and Foreign Affairs, believes that this new dynamic could lead us to a new, more egalitarian world -- or to a new Cold War.

Salon spoke to Bremmer over the phone about America's new isolationism, the cyber-attack threat and why China will never replace the USA.

You start off the book by talking about the Copenhagen climate summit. What does the outcome of that conference tell us about the changing dynamics in the world?

Frankly, the only success that was had at that summit was that Queen Margaret of Denmark managed to avoid sitting next to Mugabe from Zimbabwe. There had been so much buildup to this summit, that the climate is incredibly important and we've all finally gotten to the point where we agree that something needs to be done. It seemed like the classic area that you could get some form of global agreement on. Of course we came away with absolutely nothing.

Following the Copenhagen summit we haven't pushed harder to get stuff done, we've actually just moderated our expectations. Every country is prioritizing its own very strong agenda and there's an absence of acceptance of what the global road map should look like, what the global architecture should look like. This dynamic is increasingly true in so many aspects of the world, whether we talk about the election of a new president of the World Bank, or on how you fund the IMF (and what you do with the money once it's there), global trade initiatives, security issues in places like Syria, sanctions on Iran, bailing out the Europeans. I mean, really the principal dynamic in the world today is the fact that there just isn't anyone driving the bus. We don't have a G-20. We have a G-Zero.

Why is the G-7 an anachronism?

The G-7 is an anachronism in the same way that the United Nations Security Council is an anachronism, in the same way that the old structure of the IMF and the World Bank is an anachronism. All of that stuff basically came out of World War II, when the United States was the dominant power in the world, and it created a world order using its own capital, using its allies, building up its allies, prioritizing its values and its interests. And that world order functioned very well for us for decades but of course over the last 30 years, the underlying balance of power shifted away from this G-1 environment toward China. It hasn’t shifted to China -- it's not as if China is now the new superpower -- but toward China, and away from the developed world toward the developing world, and away from debtor states toward creditor states. When the underlying balance of power no longer in any way reflects the global architecture that you have, then at some point, clearly, a shock will come along that will be big enough to crash that system.

The end of the Soviet Union was not big enough to make that happen, and 9/11 was not big enough to make that happen, but the 2008 financial crisis was big enough. And that effectively made the G-7 an anachronism. And it did so in part, of course, because it showed some of the vulnerabilities of the U.S.-led free market system; it certainly made it harder for the Americans to rally the emerging markets behind their values and preferences. But more important, the Europeans have been almost completely absent from the global stage over the past four years, and frankly so have the Japanese, with their 17 prime ministers in 22 years. And by the way, I strongly feel this is not a book about U.S. decline. I actually don't believe the U.S. is in decline. It's much more a book about the fact that the United States is not going to do this stuff anymore and its allies certainly are not coming along, but nobody else is either.

What happened after World War II to propel America to this position?

Well, it wasn’t just that they helped win the war, it was that the economies and infrastructures of the other countries -- both victors and vanquished – were utterly destroyed, and the United States rebuilt them. Of course, that was the Marshall Plan. And that also was MacArthur in Japan. So the U.S. basically built up both its allies as well as the vanquished Japanese who surrendered, to create folks that would support a U.S.-led global system. And that worked very effectively indeed.

In polls, more and more Americans want a kind of inward focus and less involvement in the world stage -- an issue that’s also played itself out in the Republican primary. Why do you think that is?

The reason why I make the point that this book is not about whether or not the U.S. is in decline is because it’s very clear that America is the world’s largest economy, and more important, even if it weren’t, even when China becomes the largest, richest economy, China will still be a poor country. If the Americans wanted to remove Assad from power in Syria they surely could. If America wanted to bail the Europeans out they surely could; we have the money. It’s also true that if we wanted to balance our budget, we could, but we don’t. The political will doesn’t exist for that. And so much of that has to do with the political system, and it has to do also with the inward-lookingness of the U.S.

I happen to think that there has been this significant “coming apart” within the United States of the top 10 percent and the bottom 90 percent economically. But that coming apart within the U.S. is also being mirrored by a coming apart globally. And that there aren’t many Americans that are prepared to support the U.S. as the world’s policeman anymore. There aren’t many Americans that are prepared to say they benefit from U.S.-led globalization. With the levels of unemployment that exist in the U.S., with manufacturing jobs that have gone away and aren’t coming back, with Katrina and New Orleans not getting rebuilt, large numbers of Americans are saying, “We do not see the benefit from all of what the U.S. has been doing internationally.” And that will make it politically inconceivable for the U.S. to do the kind of things that it did when it was putting together the old world order. I mean, Geithner can get on a plane and go to Europe and give as much advice as he wants to. But there’s nowhere near the level of political support in the United States for the Americans to pull off another Marshall Plan in Europe, or anything remotely close to that.

And even in the case of Libya, which of course is the big intervention that happened after the 2008 financial crisis, look at what actually happened. The U.S. did not want to do it. Everyone hated Gadhafi -- U.S. enemies, U.S. allies. The Brits and the French said, You’ve gotta remove this guy. And only then did the U.S. say they would, and still the U.S. did not have troops on the ground. In some ways, Libya is the exception that proves the rule, that whether we’re talking about trade or climate or security or the European crisis, all of these are issues where we’re just not going to see the kind of leadership anywhere that we have historically.

I think many people would see this as a positive decline in so-called American imperialism.

Well, first of all there’s no question that American intervention on the military side has been seen as problematic. But for every country that sees it as problematic, others have seen it as something essential. You can talk about Marshall Plan, the role that the U.S. has played in the World Bank and the IMF, the importance of the Peace Corps and all of this sort of stuff – these have been organizations that generally have been very welcomed in terms of the benefit for the common good.

A few years ago, I remember reading endless magazine articles about how China was going to become the new superpower, and we’ll all be learning Mandarin in grade school. You don’t think that’s going to be the case.

I put that into strong question and there are a number of reasons for it. The first is that for the Chinese to continue to succeed they need to fundamentally restructure both their economy and their political system. They’re aware of this. It's an enormous challenge, it's never been attempted with a country remotely the size of China, and they'll need to do it relatively quickly. First of all, there are no guarantees that they will succeed and, even assuming that they succeed, or they even succeed sufficiently to stave off various crises, when China becomes the world's largest economy, it will still be a poor country. And I don't think we sufficiently appreciate how different that will be. They will be focused much more on ensuring that they can provide the minimum form of employment and growth and commodity inputs for their own people. The United States is a rich country. The U.S. can easily afford to spend a lot of time helping to provide public goods, acting as a global policeman across the world, and it's done that for over a century, again for good and for bad. The Chinese will not be prepared to play that role.

Look at what China's doing in the Middle East: They are interested in defending very narrow interests - economic and security interests. It's easy for the United States to say, we want to do more on the global environment, because the average American is paying attention. The average Chinese person has a very different view of the global environment. They want a car. They want their kids to be able to have an apartment. They want a proper education. Hundreds of millions of them want to get out of absolute poverty.

The last few decades have been sort of notable, because there’s been relatively little death and conflict around the globe, compared to other periods of time in global history -- a point made by the recent book, “The War on War.” What do you think the G-Zero environment means for the security of the world?

Clearly we're going to see much more conflict in this environment. And the question is what kind of conflict it will be. I tend to not see this as a world where we're going to have military and the sort of conventional warfare between major powers. Compared to the pre-WWII environment, there's so much more interlinkage between the economies of countries. But having said that, we're definitely seeing a fragmentation of the world order, compared to a globalization and statelessness that had been driven by the United States at the order of the global markets over the past decade. What does that mean? Well, first of all it means we'll see much more cyber-conflict. Much more industrial espionage. Much more direct and overt conflict between states and corporations. More protectionism. More industrial policy. Those sorts of things, I think we will see more conflict overall. I think that can spill over into military conflict regionally that won't necessarily involve the United States.

In a G-Zero environment the Middle East is much more problematic. Because absent strong US, European, Japanese, Chinese or Russian intervention, what you end up having is the Saudis, the Iranians, and the Turks playing much greater roles in terms of diplomacy and political influence, economic influence, military influence. Those countries support completely different outcomes. Clearly that means more sectarian conflict. We're not going to see more integration in the Middle East, we're going to see more disintegration, more fragmentation, more confrontation.

In the book you also suggest that we'll be see the rise of privatized warfare, using contractors like the company formerly known as Blackwater. I find that a worrisome prediction.

You know, absent U.S. intervention, you are likely to see many more local arms races, like India vs. China, for example. But you'll also see the privatization of warfare, where countries with cash will be buying mercenaries that are well-trained, whatever they can afford, and they'll be doing the fighting for them. And that will also be true in terms of folks that can engage in cyber-warfare and folks that can protect you from cyber-warfare. In a G-Zero environment, fighting of all sorts gets fragmented.

How does this affect our ability to deal with global warming?

Well, this is one of the problems I have today with the political debate. You've got so many people out there who are saying, “Global warming is horrible and we have to do something.” But it’s fairly obvious that we're not going to. And again, it's not as if the world has never been capable of dealing with climate problems. You remember, we had a hole in the ozone, and I believe it was in 1976 that there was this Montreal protocol that was going to stop putting the CFCs in the atmosphere. And it was effective.

It's very clear that this climate issue, as you mentioned, is a much, much bigger order of baggage. It's going to cause a lot of death, a lot of displacement. There will be winners as well. There will be folks who are successful economically out of climate change, but overall, it's a negative for the world economy, and it is inconceivable in a G-Zero environment that you're going to move efficiently even toward the beginning of a global solution, and so what will happen is you will have local solutions. Local solutions will not be coordinated, they will be less efficient, and they will focus on those issues that are most important to individual governments directly. In the case of the Maldives, they'll buy land and they'll move. In the case of China, they'll focus on issues that are impacting their domestic population, without worrying about what they're doing to the global public commons in terms of emitting pollutants into the air. As they need to industrialize but they'll focus much more on water, for example, because they desperately need that water for themselves.

And the U.S. and others will start focusing on geo-engineering -- looking at what can be done to potentially artificially lower temperatures and create cloud cover and, you know, all of these sort of things which 10 years ago were fanciful but now increasingly people are starting to look into seriously. But the issue is that those solutions will not be taken globally. And what will be seen as a solution by one country or a set of like-minded countries might actually be seen as very strongly against the interest of other countries and other actors.

What countries do you think are going to be helped by this new G-Zero arrangement?

There are a group of countries that I think will do particularly well in this environment and I call them pivot states. The reason I focus on these pivot states is in a G-Zero environment you need to not just focus on growth -- because there's so much more volatility in the world, you need to focus on growth and resilience together. It's countries that are able to hedge and adapt between different models of growth and integration, that don't get captured by any individual large country [that will thrive] and certain countries are particularly good at doing that.

Canada's really good at doing that. If Obama doesn't want to do the Keystone pipeline, there are a lot of Chinese that want to have access to Canadian energy. As climate change occurs, the Canadians will have this northern shipping route, which will help them to have access to folks all over the world and will help them have access to Arctic resources. They sell more timber in British Columbia to China now than they do the United States, and that's very interesting. Singapore pivots very well. Kazakhstan increasingly pivots well where Mongolia, nearby, actually doesn't because they're much more in the pocket of the Chinese. I would argue that Indonesia pivots relatively well, Turkey pivots quite well. Mexico doesn't. Ukraine doesn't.

You claim there are a few possible outcome scenarios from the G-Zero world. What are they?

The G-Zero is not the next world order. It is a global power vacuum that is not sustainable. Something will fill it, because crises will continue to grow and not be resolved and so that very process will lead to something new. And the question is what that something new is. And I think to understand what's coming next there are two questions you need to answer. The first is, what will be the relationship of the United States and China toward each other: Will they be relatively cooperative or relatively competitive? And the second is how much do other countries matter; do they matter a little or a lot? If you can answer those two questions you have a really good sense of where the world is going.

The only one of my scenarios that gets you to a G-20 that actually works is one where the U.S. and China have relatively harmonious relations and other countries matter a lot. So far we are not moving in that direction. So far we've been moving into an environment where the U.S. and China have more confrontational relations and we're moving toward an environment where other countries are indeed likely to play a fairly significant role. So you'll end up with a world of regions. That's a much more inefficient environment and it's one where pivoting is absolutely critical.

The other two possibilities are one where the U.S. and China have good relations and other countries don't matter: That's the G-2 path. That's an environment where pivoting doesn't matter so much but where nothing gets resolved unless it happens to be a priority on the agendas of both the United States and China. The U.S. does relatively well in that environment, actually, and so does the dollar. The other environment is the one where no one can pivot and that's if the U.S. and China have bad relations and other countries don't matter very much, and that is really a bipolar cold war. It's by far the worst of all outcomes, though it's not actually the one I expect.

But this is very much in process. Countries are in play right now, geopolitics are in play. We are in a process of creative destruction, globally, that hasn't occurred since after WWII.

Shares