“I’ve always wished that Mitt could understand pregnancy, and a campaign is the closest thing to being pregnant,” Ann Romney once said. “It has about a nine-month life. It’s very painful. It has a lot of ups and downs. At about nine months, you’re saying to yourself, ‘How can I get out of this?’ But then, you know, it’s over. The thing that’s nice about pregnancy is that, in the end, you have a baby.”

It was 1994, and taking the metaphor to its logical conclusion, Mitt’s first campaign for Senate in Boston was a stillbirth. Ann wouldn’t tire of the pregnancy analogy, however, returning to it over the course of her husband’s next three races (a win, a loss, one TBD) to explain why she was onboard after declaring "never again." “Mitt laughs. He says, ‘You know what, Ann? You say that after every pregnancy,’” she said in April. “And we know how that worked out – we have five sons.”

Yes, pregnancy is something Ann knows a lot about, more than "Mitt could understand," as she put it, and she seems to see a similar immutable separateness when it comes to his chosen lot. Politics and public life are things she supports, even partners in, but are uncomplicatedly not her things. Each of their roles is clear and unquestioned. She is mother, wife and helpmate, and this grueling gestation process is simply the way to the role they both see for Mitt, which is to be a great man.

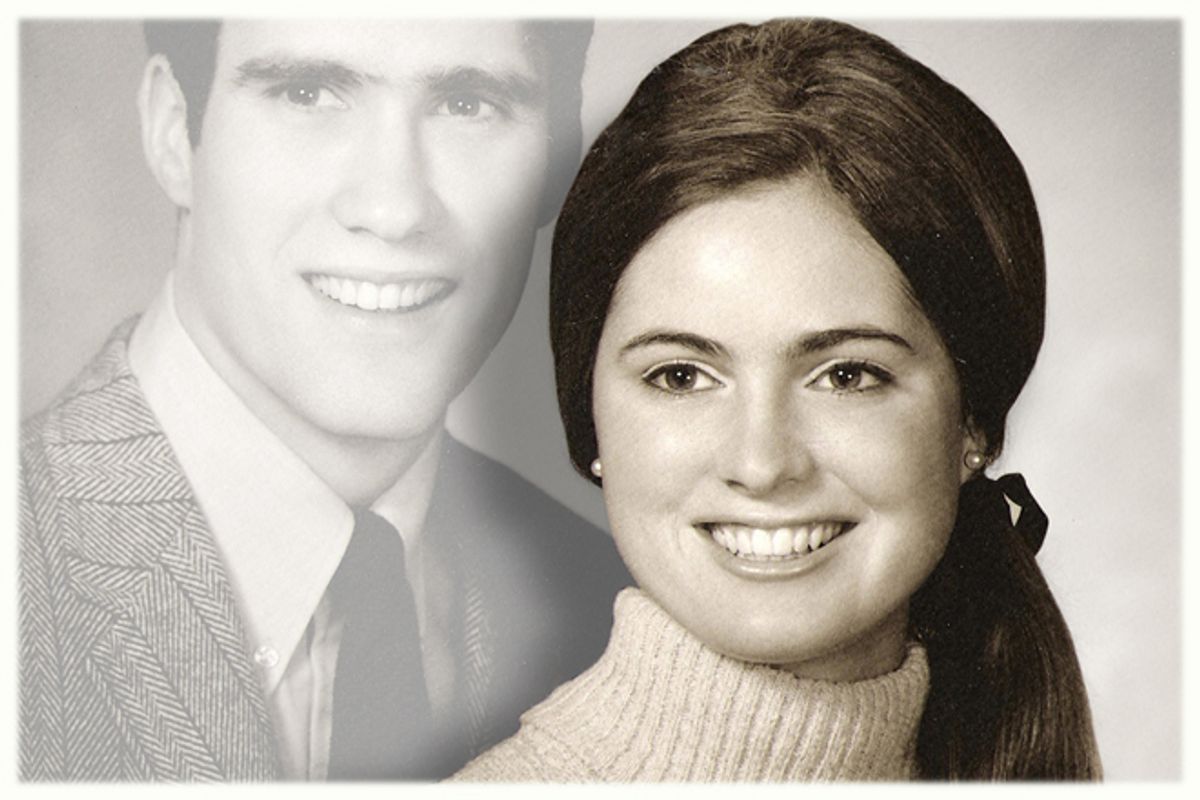

[caption id="attachment_12975110" align="aligncenter" width="460" caption="AP Photo/Jim Cole"] [/caption]

[/caption]

“I truly want Mitt to fulfill his destiny, and for that to happen, he’s got to do politics,” Ann told the Los Angeles Times on the eve of the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics. In his book “Turnaround,” Mitt says he initially resisted the offer to take over the games until Ann changed his mind. “There’s no one else who can do it,” he remembers her saying. Last year, when Mitt entered the presidential race, Ann told Parade, “I felt the country needed him … This is now Mitt’s time.” In a March radio interview, Ann declared, “He’s the only one who can save America.”

It’s not Lady Macbeth. No matter how many times Mitt describes himself as acquiescing to his wife, it’s hard to believe he has no ambition for himself or that she’s manipulating him. And it’s not, by all appearances, Ann channeling her own ambitions through her husband, as some believed Hillary Clinton did. Rather, Ann Romney is the Victorian heroine who civilizes her husband – which she signals when she talks about her husband being as rambunctious as their five sons, another boy for her to raise.

Most of all, she is, in Mitt’s own accounting, the purest muse of his aspirations, a Goethean eternal feminine drawing him aloft. Or, to pick an example closer to home for the Romneys, from Brigham Young, “Mothers are the machinery that give zest to the whole man, and guide the destinies and lives of men upon the earth.” In 1994, when they were still saying unguarded things in interviews, Mitt recalled that Ann’s mother “used to say that Ann is an angel, and the amazing thing is that Ann is an angel. I can’t think of a weakness. She really is extraordinary."

When they talk about it publicly, Mitt and Ann see their marriage in totally consonant ways: She is on a pedestal, he is her protector, but she makes him a better man. “I found her early and hung on,” Mitt told Piers Morgan this year. “When you see something that’s better than you and doesn’t know it, you just hang on to her.” Mitt, Ann famously told the Boston Globe in a 1994 interview, “never once raised his voice to me.” Equally telling, but less repeated, was her description of what she would do if he did: “I’d dissolve into tears.” They are a woman and man who not only sat out the sexual revolution but were more traditional than their parents, resisting their entreaties that they not marry so young and not have so many children.

There is no reason to believe either of them ever wanted their lives to be anything other than the apparently effortless embodiment of an old-fashioned ideal. What’s striking is that for all of Ann’s easy grace, she seems continually surprised, even indignant, that anyone would see these core values of her life differently -- not only that the rest of America hasn't lived as she has, but that it might not share her unshakable belief in her husband’s destiny.

-- - -- - -- - -- - -- - -- - -- - -- - -- - -- - -- - --

"I never think of describing myself," Ann blurted out in that guileless Boston Globe interview, asked to use three words to do so. She added, "Mitt's upstairs, should I put him on?” (She eventually came up with “peaceful, loving and serene.”) She has been derided as spoiled or entitled, but her missteps seem to be born of obliviousness, not malice. Whenever possible, money has insulated her – her father was a rich man, she married into wealth at 19 – but so did almost uninterrupted adoration.

She’s had to think about describing herself since then, and not just because her husband kept running for office. In 1998 -- after the failed campaign, around the time of the Olympic preparation, and before Mitt became governor – she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, which she has described as a loss of self. She would later say she ripped up photographs of herself from that time.

“We have an identity. My identity was mother, accomplished, doing many things, taking care of everybody, and all of a sudden I couldn’t even take care of myself. It’s like a rug being pulled out from underneath you. What are you left with? You really have to evaluate, who am I really?” she told Fox News. But she was saved by the enduring love in her life: “For Mitt, that’s where he gave me the greatest strength, because he was the one reminding me that it wasn’t what I did, why he loved me, it was who I was.”

She had found a way, at least rhetorically, to define herself in relation to others, and it was no longer as a “daughter of privilege.”

“We’ll all have a dark hour in our lives,” she said in the same interview this past May. “I am grateful that my heart has been opened up and softened, and that I can appreciate and understand when someone is going through a challenge, what it feels like.”

Ann’s illness interrupted a life of remarkable symmetry. Ann and Mitt got married four years to the day after their first date on March 21, when she was 15 and he was 18. Exactly a year later, also March 21, their first son was born. If no one has ever really witnessed discordance between them, it may be because they fervently chose each other and then essentially grew up together, rather than growing apart.

On that first date, they saw "The Sound of Music,” an appropriate and instructive cultural 180 from Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing,” which the Obamas saw on their first date. One movie for the pair of wholesome Michigan teenagers in 1965; another for the critical theory-reading pair who in the '80s met as adults, with concomitant baggage and compromises. Michelle was technically Barack’s superior at the law firm where they met – a first-generation professional who had just declared to her mother that she was going to focus on her career and not on dating – and they were both of Harvard Law. Meanwhile, having converted to Mormonism after meeting Mitt, Ann withdrew from BYU and moved to Boston for Mitt’s own Harvard Law and Business turn, during which she finished her degree in French at the extension school. (Mitt had gone to France for his mission.)

“She put aside what could have been a very interesting career, because she decided, we decided together, that we wanted children and a number of them,” Mitt told Piers Morgan this year. “And she devoted herself to them and was able to give her time to them, did a remarkable job.” It’s not clear what this “very interesting career” would have been, apart from the fairly standard traditional charitable activities she took part in through church and as first lady of Massachusetts – teaching “at-risk” girls, supporting faith-based community service. Ann Romney’s press secretary originally said she would be “more than happy” to answer questions by email, but when she received the list, including a query about what Ann’s career aspirations had been, she said she couldn’t meet Salon’s deadline.

A longtime family friend and fellow congregant, Tony Kimball, told Salon that Ann had briefly had an interior design business with her friend Lorraine Wright, who had “gone all the way through the Cordon Bleu cooking school, and Ann was the interior decorator end. She’s got phenomenal ability in decorating. But I think they both decided it was not worth the time. They were both very busy, they had kids.” According to Michael Kranish and Scott Helman’s “The Real Romney,” Ann was invited to events by the feminist Mormon group Exponent II but “was, in the words of one member, understood to be ‘not that kind of woman.’”

What kind of woman was she? Their sons call Ann the “Mitt stabilizer,” and in his book “Turnaround,” Mitt writes about how he flailed in Utah without her at his side. “Ann is my most trusted advisor; her judgment on the widest range of business, organizational, and human resources matters was more sound than any other I know. I simply could not turn around the Olympics without her daily counsel.” By all accounts, that’s still true. Romney biographer Ron Scott noted that at the first debate of the 2012 cycle, in Manchester, N.H., “Mitt’s eyes nervously scanned the audience as he spoke his first words of the night: ‘Where’s Ann?’ Spotting her waving hand in the audience, he went on confidently, bolstered by her high sign of goodwill and love.”

Michelle Obama was chided in the first presidential campaign for taking her husband down a notch, even “emasculating” him; however unfair to Obama the allegation was, no one could accuse Ann of doing the same. (Not long ago, conservative talk show host Michael Savage did find fault with Ann, once, for ardently interrupting her husband in an interview to go after Barack Obama.) In contrast to Michelle’s visible reluctance to drag her family into politics, Ann Romney’s talk about her husband's political aspirations has often been in deterministic terms. "I believe if Mitt wins, the country wins,” she told Fox News. “If Mitt loses, the country loses. I really believe that."

From the outside, Mitt’s end of the deal has always been to treasure his wife, on her own terms and as the mother of his children, in a fashion that connotes protection from the wilds of the world. “He doesn’t ever contradict my mother in public,” Tagg Romney told the Globe in 2007. Kimball told Salon, “I know that Mitt wouldn’t tolerate his boys doing any kind of backtalk to their mother.” That escalated with Ann’s illness.

All this has not been lost on conservative commentators, including Fox News’ Neil Cavuto, who also suffers from multiple sclerosis. Ann, he said, is “a woman for whom a guy who was conquering the world stopped everything when he first heard she had MS and traveled the world to find the best doctors.” Sounding like the Wall Street Journal commentator who wondered whether the women saved by their boyfriends from the Aurora shooting were “worth it,” Cavuto went on, “Ann Romney was worth the price, maybe because for this otherwise rigid Mormon husband who had a hard time showing his emotions, having a wife like Ann, who has no trouble with those emotions, was and is worth the fight.” He didn’t specify what, exactly, would make one’s ailing wife unworthy of the fight.

Politics – presenting the first and few times in which Mitt Romney didn’t get exactly what he wanted pretty fast -- has given Ann increasing opportunities to offer some of that protectiveness in return. If her sunny disposition has flickered, she is usually defending her husband, whether it’s her storming out of the room in the 1994 race when he was asked, “Can you really relate to an average voter?” or more recently, remaining obstinate to Robin Roberts on the release of more tax returns.

Like almost all of the roles Ann has played, it’s one she seems to take to naturally and enthusiastically. Every profile of Ann says it’s her role on the campaign to humanize Mitt; each time she does so she seems mildly surprised that people don’t see Mitt as she does. That includes his singular ability to “save” America, although it’s not limited to it. In April, she offered an example of his supposed humorous abandon to "Entertainment Tonight": "He doesn't comb his hair when we are not going places. It's all over the place." Still, I believed, watching it, that Ann actually does find that to be wild and funny.

Shares