If the vague, sweeping rhetoric at both major political conventions mainly concerned economic issues, from jobs to mortgages to the Republicans' witch-doctor insistence that cutting taxes on the super-rich will somehow benefit the rest of us, hardly anyone in either party mentioned the fiscal plight of America’s cities. There’s a good reason for that: The outlook is dire and getting worse. Two California cities (Stockton and San Bernardino) are already in bankruptcy and numerous other municipalities across the country are no longer able to meet debt obligations or provide basic services. In all probability, we’re entering an era when many cash-starved cities will require outside intervention. As filmmaker Heidi Ewing, co-director of the remarkable documentary “Detropia,” puts it, “That’s going to be the next bailout.”

“Detropia” is a haunting, beautiful and tragic portrait of contemporary Detroit, a city that exemplifies the lost American century in many ways, for good and for ill – and a city whose sad fate once looked like an aberration and now looks like a harbinger. Both major parties held their conventions in Sun Belt boomtowns that represent a particular (and, to my mind, a particularly depressing) vision of the urban future – a hollowed-out downtown “entertainment zone” supporting a service-sector economy and surrounded by vast rings of suburban development. Detroit, of course, represents America’s vanished industrial past; it was where Henry Ford built his empire and where the “arsenal of democracy” that defeated fascism was forged. In its current state of dereliction and instability, and also in its potential for rebuilding and reshaping, Detroit now represents the dangers and possibilities of the urban future.

In the 1950 census, the city of Detroit had a population of more than 1.8 million people. Today that number is around 700,000 and still dropping, for all the downtown redevelopment projects and the vaunted influx of young creative-class types. One of Detroit’s allures, in its golden age, was the fact that it was a sprawling city of single-family houses in the Middle American style. Today that has produced vast patches of urban blight, full of boarded-up homes and weed-choked, rat-infested vacant lots. There are believed to be at least 30,000 empty houses in Detroit, although no one has tried to count them all. Roughly 40 square miles of the city (out of a total of 143 square miles) consists of unused and unoccupied land, an area larger than Manhattan.

Ewing and her co-director Rachel Grady, the dynamic duo behind the Oscar-nominated “Jesus Camp” and the equally mesmerizing abortion-clinic documentary “12th & Delaware,” went to Detroit at first almost on a whim or an impulse. Ewing had grown up there, just outside the city limits, and had seen the small manufacturing business owned by her father and uncles struggle through the auto industry’s lengthy downturn. What they saw when they arrived in Detroit in October 2009 convinced them that what was happening there was a story with national significance, and also one that presented tremendous possibilities for film. “It was so cinematic and so immediate and so epic and so far beyond anything I had remembered,” Ewing says. For one thing, a city that’s so empty, a city with few ambulances and police cars, a city where few people go to work, offers an entirely new urban sensory experience: It’s quiet in Detroit, and this is a quiet movie.

“Detropia” is not a historical documentary that will answer all your questions about what happened to Detroit, nor is it a social-issue film that explores diagnoses and prescriptions for the future in detail. It’s a gorgeous, subtle imagistic portrait of the city as it is now, loaded up with the past and pregnant with possibility. You will meet Mayor Dave Bing, the one-time Detroit Pistons star with a controversial (but likely unavoidable) plan to save the city he loves by downsizing it, and also an African-American entrepreneur trying to keep his once-thriving nightclub open in a half-empty neighborhood. You’ll meet young Detroiters, white and black, newcomers and lifers, as they try to forge new lives and new opportunities amid the grandeur and desolation of their city. I recently met Ewing and Grady at their New York office for a conversation about Detroit, “Detropia” and America’s cities.

There are so many reasons to make a film about Detroit! But tell me what yours were.

Heidi Ewing: There are a lot of reasons that have nothing to do with me personally, but I was born and raised about four miles outside Detroit city. My dad and his brothers had a manufacturing business that made parts for the auto industry. So I had a front-row look, during the '70s and early '80s, when I was first conscious of what was happening, at how hard it was even then to stay alive. So there was definitely a personal connection, with my parents still living there. And then things around 2008 really seemed to hit critical mass. It hasn't been great in Detroit for a while, let's be honest. But it was pretty scary. Foreclosures were moving into the suburbs, my dad's friends were losing their jobs, stuff like that. So we started having this conversation around here about the city of Detroit. We said, let's go to Detroit for a short time, let's get our favorite D.P., let's get our producer. Let's go, pay for it ourselves and see what we find. So we found a guy who's selling houses on Craigslist, we filmed inside the opera house because our friend runs it, we met this guy who's driving a food truck around. It started as a visceral experience, but it didn't take us too long to realize that all roads led to Detroit, that Detroit was a national story. We were there in the very worst of times for Detroit, right after the financial crisis. So there was a personal connection, and then there was our desire to jump off a cliff and do something new creatively.

Well, let’s talk about that. This isn’t the kind of movie that explains all the history, which I know frustrated some people who saw it at Sundance who maybe wanted something more linear and discursive. Personally, I love this approach, the way you tell the story through these images and disconnected characters, the way it’s more impressionistic than a lot of documentaries. Can you talk about that?

Rachel Grady: Well, we tried to give just enough context. We have some [on-screen] cards, but very few, and a little bit of archive footage. Just as thin ligaments to this present story. It's a story about what's happening right now. We didn't want to linger in the past, because the past has been wild -- it's been more than 100 years, and Detroit has been through everything -- and the future is unwritten, right? So there's something about Detroit and where it is right now that we think is extremely translatable as a national story, as something that people can empathize with and see happening in their own community. When they probably didn't ever think that their city would have anything in common with Detroit, which has been going in this direction for 30 years. Detroit has been the butt of jokes for so long, it's been kicked to the curb, it's been dismissed.

H.E.: We thought we would stay in the present, cover this year and cover the people on the ground. Part of the impressionistic feeling you’re talking about is what is really noticeable about the city. It's extremely quiet. It's unlike other cities. There's hardly any ambulances or sirens or cops, there's hardly anybody working. There's hardly any people! I mean, there are a lot of people but they're spread out over an enormous space. So the music is very subtle, it's moody, it became more of a mood piece. We were trying to capture the mood of Detroit, and maybe the mood of the country.

Yeah, this film feels aesthetically ambitious in a new way for you guys, and I’ve heard you say that you felt that was appropriate to the subject and the setting.

Every location needs a different treatment. You stick around for a while and you ask the place, How should I treat you? How should I photograph you? That was a conversation we had a lot in Detroit. Because there is that concept of "ruin porn," and we were aware of that. We were aware of the photography books, all of that. So you don't want to overdo that -- and yet Detroiters interact with the vastness and with all these formerly grand places. They don't just walk by and not notice it! It's not just French photographers who show up and pay attention! They talk about the buildings, they notice if there's any renovation. The young kids break into the buildings. It's like their treehouse, that's what Crystal [a young African-American woman in the film] said. "You had treehouses in the suburbs. Well, we have abandoned buildings." We tried to show these spaces, and how Detroiters interact with them.

Also, in terms of photographing Detroit, the light is amazing. I remember this from growing up: In the summer in Michigan, it stays light until 10 o'clock at night. So it's one of those places that is so fun to photograph. If you squint just a little bit, if you take off your glasses, you see how grand some of these spaces were, how beautiful it was and what it maybe could be. It's a romantic place, it really pulls you in. So it was really fun for us to do this impressionistic dreamscape treatment. A lot of people project a lot of things onto Detroit, it's a dreamscape for a lot of people. So we went full throttle with that.

There has been a lot of media attention on the supposed influx of young artistic types in Detroit. We do meet some of those people in “Detropia,” but you clearly decided not to focus on that, to go with a mixture of newcomers and lifelong residents.

A lot of people have left the city, and most of the people we film, our main characters, are people who also could leave. They don't have to stay. They've got jobs and some resource. Mr. Stevens [the nightclub proprietor] doesn't have to run the Raven, open it up on Friday night when sometimes only three people walk in. He doesn't have to do it. Crystal is young and smart; she could leave. It wasn't totally conscious, but we ended up being more taken with those who are lifers, who could leave and chose to stay.

Also, you want a film to be relevant in 10 or 15 years, and this influx of new young Detroiters, artists and stuff -- you know, when they have kids, are they gonna stay? Are they gonna fix up the public schools so they can stay? I mean, is this a trend? Is it a passing fancy? We don't know, so let's just wait on that. I hope they stay, but that's not for sure. We tried not to jump in that direction too much. We kissed the arrival of the new folks and moved on. Plus, it's being so overly covered by the New York Times and everybody else: The hipsters and the young people are saving Detroit! It seems a little facile, and honestly, shouldn't we talk about the systemic underpinnings of what happened to Detroit, instead of deciding it's been saved suddenly by 2,000 people? It's kind of offensive to the other people, who've been slogging through.

R.G.: And who have never met any of these new people.

H.E.: We could have built our whole film out of, like, those four blocks of downtown, and we definitely decided not to. We had nothing to add to that narrative. Everyone else is doing it anyway, and who knows the outcome? So we ended up with a handful of people who were all having the same conversation but didn't know each other. As for the all-hailed artists, I'm glad they're coming and all, but you know what? They're opening expensive restaurants and coffee shops, and they all frequent each other's businesses. Most Detroiters are being left out of that economy. I hate to be a downer and be yelled at, but we should be conscious of this extra divide that comes with gentrification, and I don't think we should pretend it's not also gonna happen in Detroit. There's got to be some kind of communication between these groups. A lot of these people arriving are like, "This is Dodge City, man! I can do whatever the hell I want! It's a blank slate!" Well, Detroit is not a blank slate. That colonizer's attitude? You guys should tone that down, because there are people who've lived there a long time.

You show us some of the debate over Mayor Bing’s plan to essentially downsize the city, to turn off the lights and services in certain neighborhoods, move everybody out, and turn them into open spaces or community gardens or whatever. I get why residents were horrified by that, but isn’t some version of that unavoidable? The city does not seem sustainable with its current population and in its current form.

R.G.: It isn't at all sustainable in its current form. We waited around hoping that we would have a card at the end of the film telling you what happened to that plan. Well, there's no card. It's been suspended for a long time, and now they say they're back at it. But I would say the key word in your question is "debate." The debate is over. There's no back and forth anymore. They're not asking for citizens to go to town halls and give their impressions anymore. The city is shrinking itself quietly. They're just simply broke. They can't afford to pay people. And it's not even up to them. DTE, the power utility, is a private organization, and they're telling people, “You know what, we can't keep these street lights on. If you want them, you owe us $14 million!”

H.E.: We are many moons away from a plan on what neighborhoods to invest in and which ones to give up on, but it's just happening. They can't force people to move, they realize that. If they paid people to move, they probably would. But they don't have the money. It's gonna be like this: “You don't have to move -- but the garbage is not gonna get picked up but once every two weeks. We're not gonna make you move, but you're kind of on your own.”

R.G.: It's not even denial of service. Everyone has left the building! Denial carries the implication that they have the ability to do it and they won't.

H.E.: I'm sure Mayor Bing is up all night thinking about this stuff. He inherited an impossible job. They've got, what, a $129 million budget deficit? Everyone took a 10 percent across-the-board pay cut. So the average salary [for city employees] has gone from $26,000 to about $20,000. What else are we gonna cut? I mean, they're gonna try to cut their way out of this, but when you're talking about city services, cops and firefighters, that's a dangerous game. Detroit needs a bailout. Many cities are going to be looking for a bailout.

How widespread is this disease? Are we looking at a lot more Detroit-scale urban disasters in the years ahead?

Look at Stockton, which actually went bankrupt. Detroit would have been the largest city to go bankrupt, and that was prevented at the last minute. The idea that a city, or an entire state would go bankrupt -- California is screwed, Birmingham, Ala., is in deep trouble. The concept that these places would go bankrupt -- if we could go back in time, nobody would believe that was possible.

I know a lot of people who don’t live in cities may kind of shrug their shoulders and say, fine, let them go bankrupt. But aren’t the consequences of that pretty dire, and likely to have an economic ripple effect that is not easily contained?

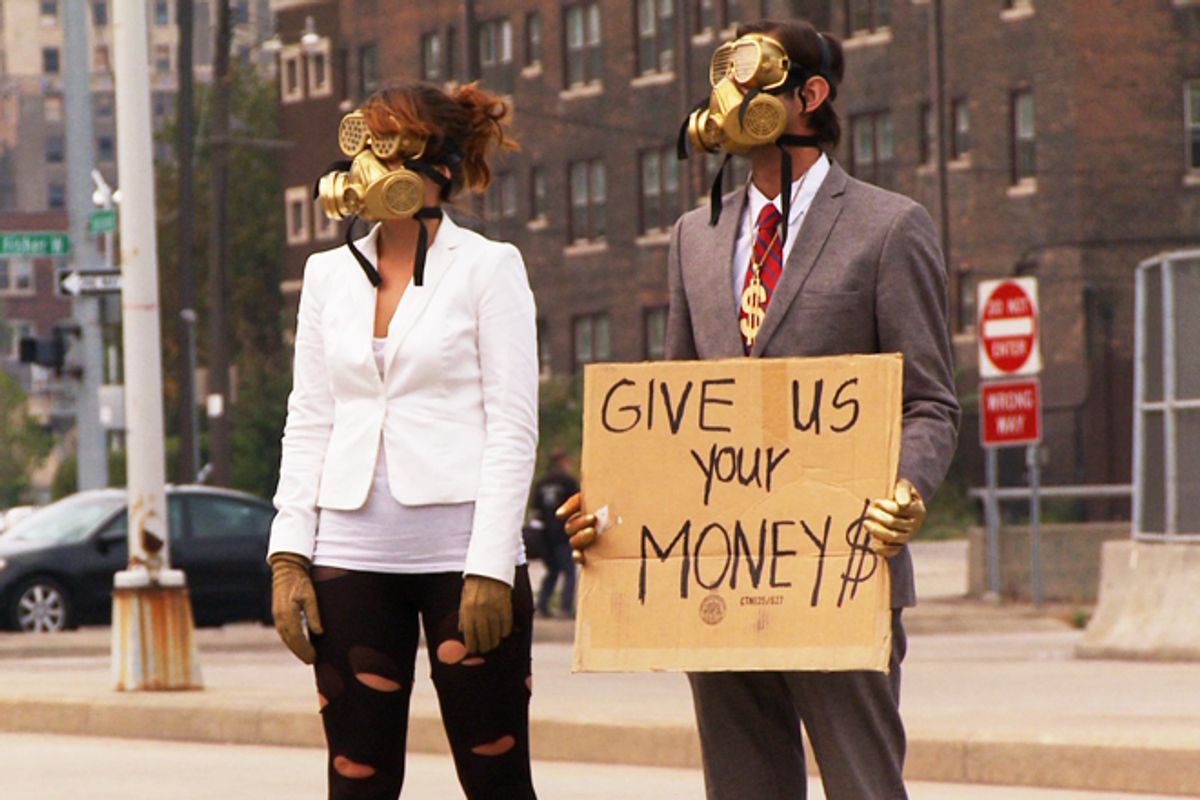

If Detroit were to go bankrupt, an emergency financial manager takes over, and they have the power to end collective bargaining and fire anyone at will, including elected officials. Do you think anyone ever gets those rights back? We're seeing this moment where they can take hold of a city or a union and just whittle it all the way down. It's happening with public unions, private unions, cities. It's a very scary time in this country, and we're going to start seeing this in more and more places. You're seeing an emboldened corporate America just going, “Once and for all, guys, we're gonna cut off the limbs.” They've got the upper hand because nobody wants them to leave. They'll just go to Mexico and pay $3.52 an hour, benefits included, which is what American Axle, the company that leaves Detroit in our movie, is paying its workers.

You know, the fact that young college graduates are coming to Detroit is not just because it's a cool spot. It's largely because they can actually afford to live there.

I’ve heard a lot about that. It’s actually somewhat tempting. What can I buy a house for in Detroit? You know, something nice, or at least something OK.

R.G.: There are some houses for $500, but those are totally gutted. You can get a house that's standing and solid, but needs some work, for around $7,000. Or you could just buy a house that's in perfectly good shape for $25,000 or so, and forget about doing the work.

H.E.: You can buy a beautiful, beautiful mansion in the Boston-Edison district, where all the auto company executives used to live, for $139,000. An absolutely incredible house, still with all the mahogany banisters and chandeliers. But you better not need the police, and I'm not joking. You better know how to use a shotgun.

"Detropia" is now playing at the IFC Center in New York. It opens Sept. 14 in Ann Arbor, Mich., Detroit and Washington; Sept. 19 in Boston; Sept. 21 in Chicago, Grand Rapids, Mich., and Providence, R.I.; Sept. 24 for one night only in numerous cities in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Missouri; Sept. 28 in San Francisco; Oct. 5 in Los Angeles, Santa Fe, N.M., and Toronto; Oct. 10 in Stamford, Conn.; and Oct. 12 in Hartford, Conn., and St. Louis, with more cities to follow.

Shares