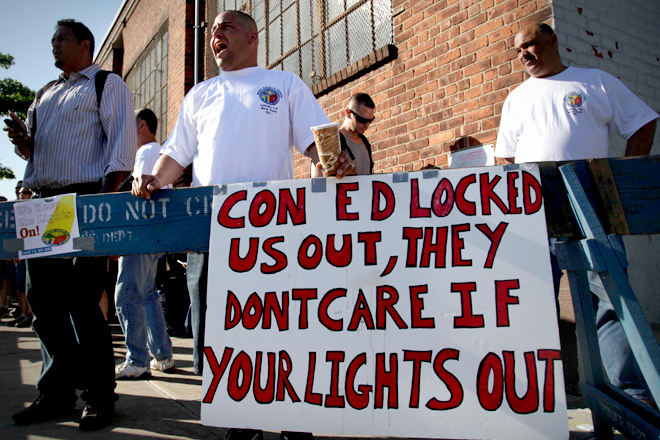

Last night, three days after a blown call that had even Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker pleading to “#Returntherealrefs,” football’s union referees were back on the field. Just before midnight, management announced a deal had been reached on a new contract, ending a lockout marked by questionable calls and — worse — unsafe but unpunished hits. As the “replacement” refs depart the field, talk of lockouts will fade from the news — but they’ll remain a growing trend in labor struggles across the country.

The refs’ lockout was not a strike. In a lockout, union members are out of work not because they’ve walked off the job, but because management has refused to let them work. (Of course, plenty of bona fide strikes are intentionally provoked by management.) This distinction was lost on most national media outlets this week, as demonstrated by a string of corrections on articles that had originally referred to “striking” referees. CNN correspondent Jim Acosta even asked Mitt Romney what he would “do about those referees,” and whether he would “order them back to work.” Under U.S. labor law, when union contract negotiations break down, management can lock workers out until they reach an agreement. In other words, if you won’t give up as much as your boss wants at the bargaining table, he can put you out of work until you come around.

As workers lose ground to management, strikes are losing ground to lockouts. In the 1990s, just 4.1 percent of work stoppages were lockouts, according to Robert Combs of Bloomberg BNA; in the first quarter of this decade, 8.3 percent were. In the same period, the number of strikes has plummeted. In fact, as the New York Times reported in January, the ratio of lockouts to strikes hit an all-time high last year.

The reason the ratio of strikes to lockouts is shifting, says Columbia political science professor Dorian Warren, is that “workers have seen a decline in their bargaining power for the last 30 years, while employers have seen an increase.” The weakness of labor law and the aggressiveness of employers, he adds, have reduced the strike to “a weak weapon” for many workers. Lockouts “are symptomatic of a broader trend of employer militancy,” says Gary Chaison, a professor of industrial relations at Clark University. “The lockout,” he adds, “even though it’s probably the strongest, most anti-union act an employer can do, is increasingly seen as a pragmatic decision about bargaining strategy.”

At the start of 2012, 2,607 workers were already locked out. Most of them still are. Among them: Becki Jacobson, a 30-year employee who’s one of 1,300 workers locked out by American Crystal Sugar in Minnesota, North Dakota and Iowa. In summer 2011, the sugar beet cooperative forced union members to train their own replacements and then, after 96 percent of workers voted to reject deep concessions on healthcare and job security, locked them out. “Every time we went to negotiate,” Jacobson told me in a March interview, “the company refused our proposals and kept going back to their first and final offer.” The company’s CEO, Dave Berg, was caught on tape telling shareholders that the union contract was like cancer, and the lockout was the treatment: “At some point that tumor’s got to come out. That’s what we’re doing here.” But Crystal Sugar hasn’t been convicted of breaking any laws.

Like the NFL’s and Crystal Sugar’s, lockouts often go hand in hand with another trend in Great Recession-era bargaining: demands for new concessions from workers, like shifting healthcare costs to employees or doing away with pension plans. Indeed, while the NFL’s owners may have permanently damaged their brand in the lockout, a statement issued yesterday suggests they succeeded in phasing out the workers’ pension plan over time.

Some lockouts are a response to union strength, says Kate Bronfenbrenner of Cornell University, as employers try to get the upper hand against unions they worry will become strong enough to strike. “If it looks like the union’s going to fight back, then they beat them to it,” she told me. In other cases employers lock workers out because they sense a union’s weakness, and want to go for the kill.

As employers threaten to throw workers out of their union jobs unless they sacrifice their union benefits, a union member’s fight to renew his or her contract can look more and more like a non-union worker’s struggle to win one. In both cases, workers can’t count on the law to secure them justice (a multimillion-dollar fine against a California country club – awarded to locked-out members of a union affiliated with my former employer, UNITE HERE — is the exception, not the rule). Faced with employers on the warpath, some unions turn to disruptive activism or consumer, media and political pressure. Some still end up agreeing to painful cuts.

When Republic Services locked out sanitation workers in Indiana, fellow Teamsters in other cities went on strike in solidarity. When Sotheby’s auction house locked out its art handlers, Occupy Wall Street activists crashed art events with chants and banners. And over the past several months, workers have tried a range of tactics to pressure Crystal Sugar, including targeting a bank that invests in the company, raising awareness with a multi-state bus tour, and picketing outside of recruitment fairs. On Tuesday, hours after the referees’ lockout cost the Packers a rightful victory, 37 members of Congress released a letter calling for a resolution to the Crystal Sugar strife.

Unlike the NFL’s returning refs, other locked-out workers can’t count on governors like Scott Walker to take their side. But in each of these cases, just as in the NFL, the balance of power between labor and management depends in large part on the public. Do customers let themselves become accomplices to union-busting? Or – whether out of fears for safety, concerns over quality, or loyalty to local workers — do they rebel?