Suppose someone gave a manifesto and nobody came?

In 1989, two years after "Bonfire of the Vanities" was published, Tom Wolfe wrote a 10,000-word essay for Harper’s. “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast” was, Wolfe wrote, “a literary manifesto for the new social novel” and a shout-out for literary realism.

After World War II, Wolfe argued, “Among the fashionable European ideas that began to circulate was that of ‘the death of the novel,’ by which was meant the realistic novel. Writing in 1948, Lionel Trilling gave this notion a late-Marxist twist that George Steiner and others would elaborate on. The realistic novel, in their gloss, was the literary child of the nineteenth-century industrial bourgeoisie. It was a slice of life, a cross section, that provided a true and powerful picture of individuals and society – as long as the bourgeois order and the old class system were firmly in place. But now that the bourgeoisie was in a state of ‘crisis and rout’ (Steiner’s phrase) and the old class system was crumbling, the realistic novel was pointless. What could be more futile than a cross section of disintegrating fragments?”

By the early 1960s, “the notion of the death of the realistic novel had caught on among young American writers with the force of revelation. This was an extraordinary turnabout. It had been only yesterday, in the 1930s, that the big realistic novel, with its broad social sweep, had put American literature up on the stage for the first time …” It was the lefties, then, who did away with the kind of novel Wolfe loved.

Wolfe noted that when Sinclair Lewis won the Nobel Prize in 1930, “four of the next five Americans to win the Nobel Prize in literature – Pearl Buck, William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, and John Steinbeck – were realistic novelists.” Yet by 1962, when Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize, “young writers, and intellectuals generally, regarded him and his approach to the novel as an embarrassment. Pearl Buck was even worse, and Lewis wasn’t much better. Faulkner and Hemingway still commanded respect, but it was the respect you give to old boys who did the best they could with what they knew in their day. They were ‘squares’ (John Gardner’s term) who actually thought you could take real life and spread it across the pages of a book.”

Wolfe was arguing against what he called “one of the axioms of literary theory in the Seventies ... that realism was ‘just another formal device, of a permanent method for dealing with experience' (in the words of the editor of The Partisan Review, William Phillips). I was convinced then – and I am even more strongly convinced now – that precisely the opposite is true.”

Then came the call to arms: “At this weak, pale, tabescent moment in the history of American literature, we need a battalion, a brigade of Zolas to head out into this wild, bizarre, unpredictable, hog-stomping Baroque country of ours and reclaim it as a literary property.” If not, he warned, “Unless some movement occurs in American fiction over the next ten years that is more remarkable than any detectable right now, the pioneering in nonfiction will be recorded as the most important experiment in American history,” and it might actually dethrone the novel.

Twenty-three years later it seems that no one followed Wolfe up the slope. Wolfe’s manifesto inspired no followers; no one went to battle for literary realism but Wolfe himself. Or, at least, no one else went to fight for Wolfe’s idea of literary realism.

Looking back on Wolfe’s manifesto, which now seems as dated as many of the writers he wrote about, some questions arise.

Wolfe praises Zola’s 1885 novel "Germinal" as a forerunner of realistic fiction because of the author’s careful and precise reporting on French miners, which may well be true, but nearly 130 years later does anyone really want to cite "Germinal" as essential reading? (Is it even Zola’s best novel?) Does Wolfe really think Sinclair Lewis was the greatest American novelist of his time? “Was it reporting,” he asks, “that made Lewis the most highly regarded American novelist of the 1920s?” Surely Wolfe framed the question to get the answer he wants. Lewis was highly regarded, but was there anyone in the 1920s who thought him more exciting or interesting than younger writers like Fitzgerald, Hemingway and Faulkner? Who reads Lewis today before reading those three? (Or even before Willa Cather, whom Lewis thought was the best novelist of the period.)

Can Hemingway and Faulkner be jammed into the pigeonhole of “realistic novelists” as easily as Pearl Buck? And does anyone now want to go back to Pearl Buck to find out? Those who read them today enjoy them more for their style than for their adherence to any concept of realism or naturalism.

Finally, if American novelists were allowing journalists to supplant them in the literary hierarchy, why does it matter? Who cares when they are reading a great nonfiction book — such as Mailer’s "Of a Fire on the Moon" or "The Executioner’s Song" or Wolfe’s "The Right Stuff" – whether it is fiction or nonfiction? It’s great literature.

Why, exactly, did and does it matter so much to Wolfe? I think perhaps because two years earlier, when Wolfe had written his first huge novel of social realism, "Bonfire of the Vanities," he took a lot of hits not only from critics, no doubt a number of them lefties who didn’t like Wolfe’s conservative bent. So much to Wolfe. I think the essay was self-serving. It wasn’t really a manifesto but an apologia for the kind of novel Wolfe had written and wanted to continue to write. Nine years later, in 1998, he published another huge novel, "A Man in Full," this one set in Atlanta; a third, "I Am Charlotte Simmons," took place at the fictional Dupont University, which Wolfe called “Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Stanford, Duke, and a few other places all rolled into one.”

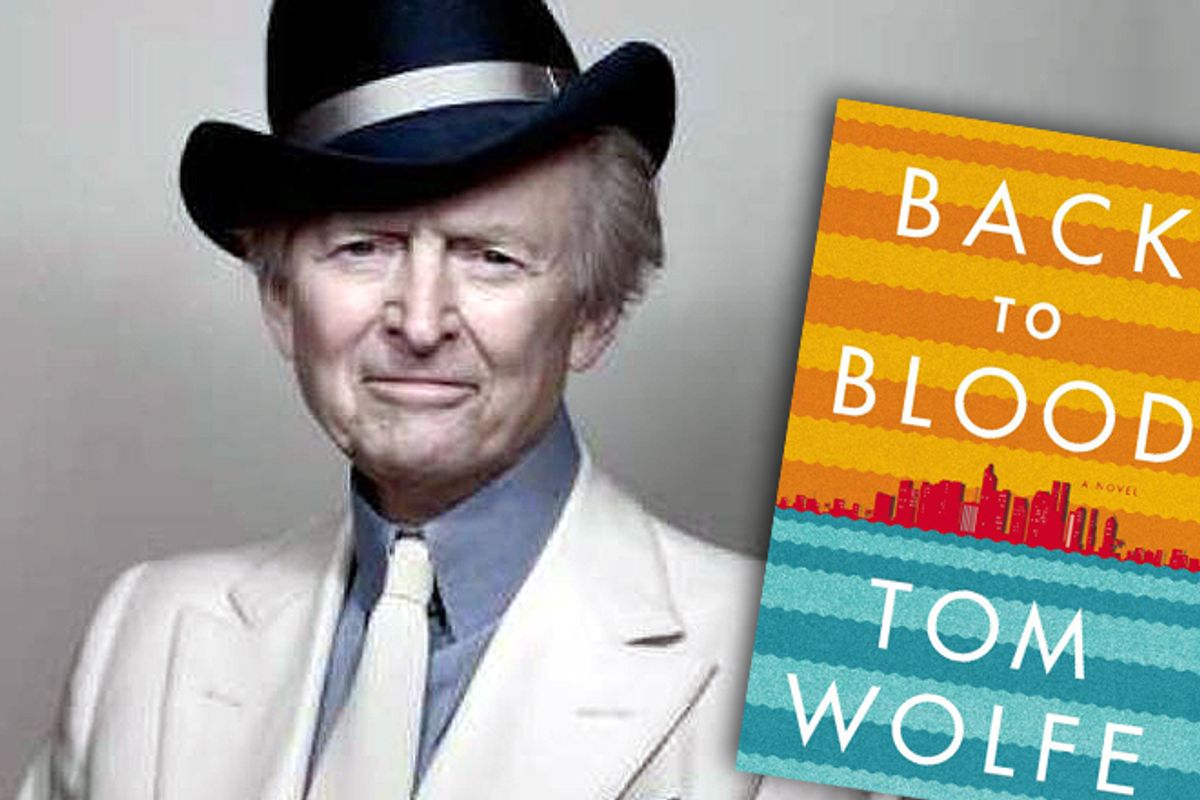

And now we have "Back to Blood," set in Miami, which, we are reminded, “is the only city in the world – in the world – whose population is more than fifty percent recent immigrants … recent immigrants, immigrants from over the past fifty years.”

If you have read all of Wolfe’s novels, you have read one of them. As in the others, "Back to Blood" has lengthy interior monologues by different characters, which, no matter what their social and ethnic background, have the same tone: loud! Much of their thought is expressed in italics, and each is allowed just one primary motivation, some kind of ambition, almost always money, sex or status -- and, in a few cases, revenge.

"Back to Blood" is a series of racial powder kegs, the first ignited when a Cuban-American police officer rescues a would-be Cuban immigrant who has climbed to the top of a ship’s tall mast. That is, the cop, Nestor Comacho, thinks of it as a rescue, but most of his fellow Cubans, resentful that the man is sent back before he can set foot on U.S. soil and become a refugee, do not. The rest of the novel is a succession of plot twists that Wolfe cleverly uses to introduce new characters. Nestor (careful you don’t pronounce it “Nes-ter,” which apparently offends Cubans, but Nes-tor) is befriended by an Americano newspaper reporter named John Smith, who sees the cop as a window into the Miami demimonde. Nestor becomes involved with a Haitian-American girl, Ghislaine Lontier, which lets Wolfe tell us how much some Haitians want to be considered French and how others, like the girl’s younger brother, want to behave like the members of African-American gangs. There’s a black police chief who is pressured by the Cuban-American mayor to transfer Comacho into a unit that will put him out of the public eye. And we also have Magdalena, Nestor’s ex-girlfriend, who gets mixed up with a famous and notorious psychiatrist who treats sex addiction – just think of the possibilities -- and who then gets mixed up with Russian gangsters who deal in art forgeries … OK, that’s enough plot.

Wolfe puts his characters into a great many complex situations, but it’s the situations that are complex, not the characters. (There are no normal people with modest desires or aspirations in Wolfe’s novels.) The prose is written to be read fast; the first time characters appear they’re given thumbnail sketches that are never expanded on. “Mac,” we’re told, “was an exemplar of the genus WASP in a moral and cultural sense." A female character “was the WASP purist who couldn’t abide idleness and indolence, which were stage one of trifling and shiftless.” That is all you’ll ever know about them, all Wolfe thinks you need to know.

Latin characters are defined by their insults: “Oh, why didn’t you just jump into the river and drown, you miserable little maricon!” The extent of Wolfe’s incursion into the Latin mind is the phrase “Dios mio!” I began counting the number of times the phrase is used and quit after 100.

Russians talk like this: “Belief me, I cannot zink of any fate vorse. You are a police officer. How much you like it eef somebody comes een and you zink he knows about ‘Ze cops,’ and you must tell him … You crazy en vone veel!?” (I haven’t a clue as to what ‘vone veel’ means.)

This is supposed to be a glimpse inside Nestor’s mind: “Hialeah is Cuba. It’s surrounded by more Cuba … All of Miami is ours, all of Greater Miami is ours. We occupy it. We’re Singapore or Taiwan or Hong Kong … But somewhere in our hearts we all know we’re really nothing but a sort of Cuban free port. All the real power, all the real money, all the real excitement, all the glamour, is the Americanos’ …” Is that really how Cuban Americans think of themselves, as part of Singapore or Taiwan or Hong Kong? Whose collective unconscious is Wolfe tapping into here? His characters’ or his own?

Wolfe’s non-white people -- whether of African-American or Cuban descent -- never come together. They remind me of 1950s movies where American Indians or Mexicans or European immigrants were always played by white Hollywood actors, Jeff Chandler or maybe Debra Paget in heavy makeup.

I don’t know how many notebooks Wolfe filled while on his excursions through Miami’s Haitian and Cuban neighborhoods in his white suit, but from what I read in "Back to Blood," the only thing he documented is the inner workings of his own mind when confronted with subcultures more exotic than his own. All Wolfe’s literary huffing and puffing can’t capture in 700-plus pages a Miami that comes naturally to genre writers like Charles Willeford or Carl Hiaasen in a 200-page paperback.

"Back to Blood" isn’t realist fiction, it isn’t naturalism. It isn’t like a novel at all; it’s more like a treatment for a very long miniseries. In the end, Wolfe seems to have forgotten his own manifesto.

Shares