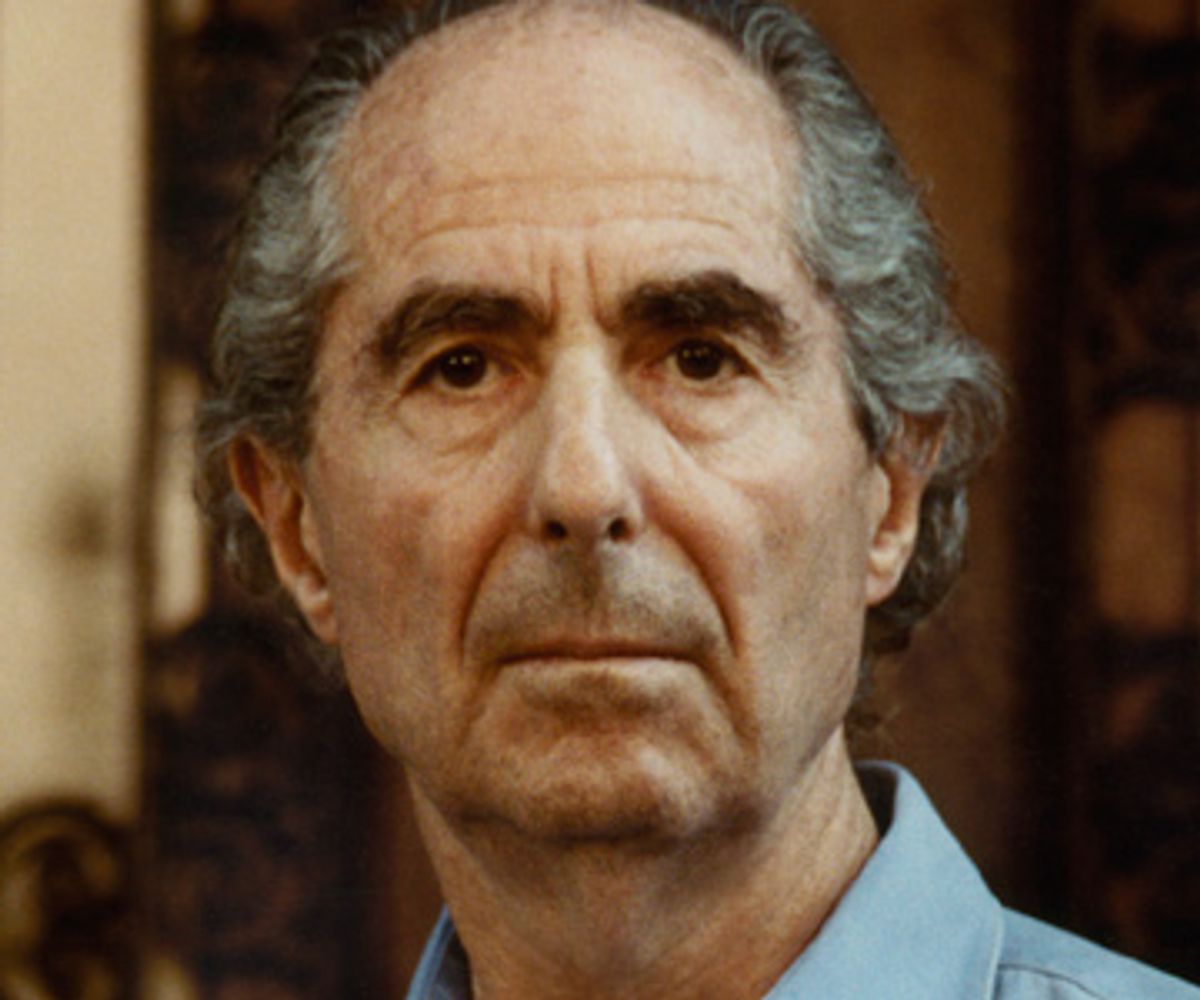

No one should have been surprised when Philip Roth casually announced in the French magazine Les Inrocks that he was retiring. At 79, Roth is the celebrated author of 31 books (all of them impressive, many of them masterpieces), the winner of just about every major literary award but the Nobel, and though he has remained remarkably prolific, his four most recent novels have been brief, spare, and uncharacteristically quiet; reading them, one has the sense of looking through a camera as the aperture slowly contracts.

“I have dedicated my life to the novel,” Roth explained. “I studied, I taught, I wrote and I read. With the exclusion of almost everything else. Enough is enough!”

Yes Roth is hanging up his gloves, and this deviation to a boxing metaphor is by no means accidental: in Roth’s books, everything is a fight. It was the combative, oppositional nature of his storytelling that mesmerized me when I first read him. His characters go after each other with a staggering vitality, clashing conversationally, emotionally, politically, philosophically, and erotically (sometimes all in the same scene), and in their spirited exchanges of outrage and defiance, accusation and desire, Roth moves the reader beyond the simple bloodlust of watching a fight ringside to the dark and disquieting self-revelations that scare us.

It’s not that Roth is in the business of dispensing great truths. He is far too smart for that. He batters with uncertainties, pummels the reader (and his characters) with ambiguity, dissatisfaction, and error. Roth is the master of error. He spends much of "American Pastoral" chronicling how our lives are nothing but a series of mistaken interpretations. “You fight your superficiality, your shallowness, so as to try to come at people without unreal expectations, without an overload of bias or hope or arrogance, as untanklike as you can be …” observes Nathan Zuckerman, Roth’s frequent stand-in, “and yet you never fail to get them wrong. You might as well have the brain of a tank. You get them wrong before you meet them, while you're anticipating meeting them; you get them wrong while you're with them; and then you go home to tell somebody else about the meeting and you get them all wrong again.” And in case anyone hopes that writers possess some privileged access to the truth, Zuckerman also announces, “Writing turns you into somebody who's always wrong.” Two books later, in "The Human Stain," a novel predicated on the idea that an entire life can be a deception, Roth returns to this motif with Zuckerman’s assertion that, “All that we don’t know is astonishing. Even more astonishing is what passes for knowing.”

And yet, our not knowing does nothing to keep most of us from believing and passionately proclaiming that we are right. One of Roth’s most effective techniques is to have a character systematically build an argument that seems irrefutable, and then for another character to come along and, tank-like, destroy it. A second, equally persuasive, argument is constructed — only to be demolished and replaced by a third argument, et cetera. In "Operation Shylock" — besides "The Human Stain," Roth’s most explicit novel about imposterhood (tagged with the impish subtitle "A Confession") — he goes on and on with this game, first building and then dismantling, first conviction then discredit, like some parodic refutation of the Hegelian triad, thesis and antithesis lurching ever onward with no chance of generative reconciliation. Twenty-seven years ago, in "The Counterlife," Roth applied this technique to the art of narrative itself, hammering home the idea that even our lives are fragmentary, misunderstood, and unknowable.

When I was in college, I gave a hardcover copy of "Sabbath’s Theater" to my girlfriend’s mother for her birthday. I hadn’t read the book yet, just plucked it from the best-sellers rack at the university bookstore while rushing between classes — and of Roth’s work itself, I had only read "Goodbye, Columbus" — and it never occurred to me that a novel with a shiny National Book Award winning gold sticker on the jacket might be an unsuitable gift for my girlfriend’s mother. Clearly, undeniably this book was literature, and in my 19-year-old mind literature meant safe, sterile, sexless.

A few months later, I was visiting my girlfriend at her mother’s house when I saw the thick red-jacketed book tucked away on the living room shelf. “Did you like it?” I asked with what now seems supernatural innocence. “It wasn’t … he’s not really … I didn’t read much,” her mother stuttered and, grimacing politely, shuffled out of the room to get her daughter. Taking the book down from the shelf, I flipped to the first page and read, for the first time, the opening salvo of the lisp-inspiring novel.

“Either foreswear fucking others or the affair is over.“

Uh-oh.

I turned my back to the door and hunching my shoulders protectively, continued to read. “This was the ultimatum, the maddeningly improbable, wholly unforeseen ultimatum, that the mistress of fifty-two delivered in tears to her lover of sixty-four on the anniversary of an attachment that had persisted with an amazing licentiousness — and that, no less amazingly, has stayed their secret — for thirteen years.”

I closed the book, slipped it into my backpack, and we never discussed it again. When I returned home that evening, I stayed up all night reading the novel. In the morning, I skipped my classes and reread the first section in a residual stupor. I was the young, hardworking, academically accomplished but sheltered son of immigrants, a boy more in line with "Goodbye Columbus’s" Neil Klugman than Mickey Sabbath. Sabbath, Roth’s most diabolical character, is a man raging at failure, at grief, at loneliness, but most of all at death, death with its infuriating senselessness, its artless stupidity; he is a man spinning out of control, a man contemptuous of control, a former puppeteer left with nothing but a vicious wit and a pitiless lust. Mickey manipulates, torments, and takes advantage of people; he is reckless and mean, funny and charismatic, ferocious and heartbroken. He was nothing like my father, a sensible, industrious, and laconic family man. And yet Roth’s fearlessness in writing "Sabbath’s Theater" — he didn’t just put “fuck” in the first sentence, he put fucking at the heart of the novel… and won an award for it! — combined with the outrageous velocity of the narrative voice, convinced me that Roth was the new father that I needed.

It’s not the grand disloyalty that it sounds. That boyhood transfer of heroic admiration from father to father figure is common — Roth explores this theme himself in Nathan Zuckerman’s relationship with his literary idol E.I. Lonoff in "The Ghost Writer," as well Nathan’s teenage veneration of Ira Ringold in "I Married A Communist" — and I’m far from the first writer to feel this way about Philip Roth. The intelligent indignation! The dialectical onslaughts! And most of all, those sentences! Each one wildly alive and thrashing like a snake — muscular, vital, dangerous, unpredictable. Over the years, by virtue of his continuing literary mastery — and, of course, his literal survival — Roth has justifiably become the great All-Father of American fiction. Men and women alike fall for the brilliant, hermetic and articulate persona; he is the hawkishly charming, notoriously seductive, roguishly funny father we all want for ourselves.

The trouble with fathers, however, is that along with admiration comes rivalry. We want to prove ourselves as equals. As time passes, we aspire to inherit power, to take the throne. On the back of Jonathan Franzen’s new essay collection,"Farther Away," right up there in top position, is a blurb from Philip Roth that surely caused two dozen of the most talented contemporary American writers to groan with sibling rivalry when they first laid eyes on it. “There are about twenty great American novelists in the generations that follow me. The greatest is Jonathan Franzen.” Of the thousands of lines of praise that Franzen has rightfully received in his career, that tribute by Philip Roth is the one he wanted everyone to see above all others. Anyone would. It is the one that counts. It is the passing of the crown.

Inside "Farther Away," halfway through his essay “Autobiographical Fiction,” Franzen admiringly brings up Roth when discussing literary friends and enemies (though Franzen eschews any familial metaphors), explaining that, “For a while, Philip Roth was my new bitter enemy, but lately, unexpectedly, he has become a friend as well.” I don’t know if Franzen moved away from feelings of competitiveness because of his majestic Roth-ian tap on the shoulder or because of a more generalized emotional shift (those birds have really sweetened Franzen, I have to admit), but I do know that the news about Roth’s retirement, however unsurprising, truly rattled me, stripping away any Oedipal longing I may have once — foolishly, impossibly — possessed, and replacing it with fear.

Perhaps I am being irrational and sentimental because only last year my real father passed away, but it is hard to imagine a long, happy senescence for Philip Roth. His announcement has the whiff of mortality to it. Here is a man who lived a life of constant literary engagement — “I turn sentences around. That's my life. I write a sentence and then I turn it around. Then I look at it and turn it around again” — a masterfully eloquent novelist who believed, nonetheless, that writing was not about fluency but about conflict: “You’re looking, as you begin, for what’s going to resist you. You’re looking for trouble.”

Only Roth, the infamous literary troublemaker, is finally, improbably, no longer looking for trouble.

All can we do now, his worried, illegitimate literary children, is to thank him, read him, and wish him more of what he already has: the best.

Shares