The Museum of Broken Relationships, which opened in Zagreb in 2010, is an eight-room gallery of debris left behind by breakups. There’s a cellphone, a wedding dress, a glass horse and a pair of male underpants; also a garden gnome, a set of furred handcuffs, a prosthetic leg and an ax. These exhibits are donation-based, and though the collection aspires to universality it may take a certain kind of personality to give away this kind of keepsake. The ax (“The Ex Ax”) once belonged to a lesbian in Berlin: She used it to chop up the furniture left behind by the woman who broke her heart. She called it her “therapy instrument.”

The caption doesn’t tell if the woman ever came back for the smithereens. But that’s what the late David Foster Wallace did, during another crisis of love in which the woodwork got the worst of it. Wallace’s biographer, D.T. Max, tells the story in "Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story: A Life of David Foster Wallace": "[Mary Karr and Wallace] split up … Soon afterward, he got so mad at her that he threw her coffee table at her. He sent her $100 for the remnants. She had a friend who was a lawyer write back to say she still owned the table, all he’d bought was the 'brokenness.'”

Max reads "Infinite Jest" as a thousand-page annotation of its author’s “dysfunctional yearning” to get back together with Karr, the alcoholic Texan poet who became a teetotaling Catholic autobiographer and for a while was Wallace’s girlfriend. In an interview, Max adduces a fragment from Wallace’s notes: “'Infinite Jest' was just a means to Mary Karr’s end.” The biographer points out the pun. Wallace wrote her letters signed “Young Werther.”

Schmaltz, self-absorption, high-handedness and wrangling over cash, the odd foray into amateur carpentry: The particulars will always be peculiar, but there’s little here to surprise anyone who’s ever endured a breakup. Some people weep, some people rant, some take their time and others take a hint. I have a close friend who prides himself on the poise with which he receives the news. “It’s probably worth going out with me,” he said, “just for the pleasure of breaking up with me.” A dreamy frown played on his features. I don’t date online, but it didn’t seem inconceivable as a selling point on OKCupid. After his girlfriend dumped him, a different friend discovered oxycodone.

I’ve always thought that nothing really ends unless it ends badly. But some breakups, it cannot be ignored, are so bad they end in a book. It’s inevitable that most of the people who write these books should also have written other books, though they tend to be writers you’ve never heard of. In "Too Good to Be True," Benjamin Anastas’ account of being left by his wife amid other disasters, the author describes himself as a “midlist cuckold.” He’s not wrong; the quip is typical of a book in which clever phrasing always seems to come at a cost of shattering embarrassment to the author. (“I … had a highly developed relationship to my pocket change.”) Bluebloods like Wallace, on the other hand, have generally left their biographers to uncover the melodramatic details of their love lives, and it’s easy to see why. A breakup isn’t a promising literary setup. Like sex and dreams — two other regions notoriously impregnable to the writer of prose — breakups are both transcendently universal and tediously individualized. We’ve all been through them. Now do we want to read about them?

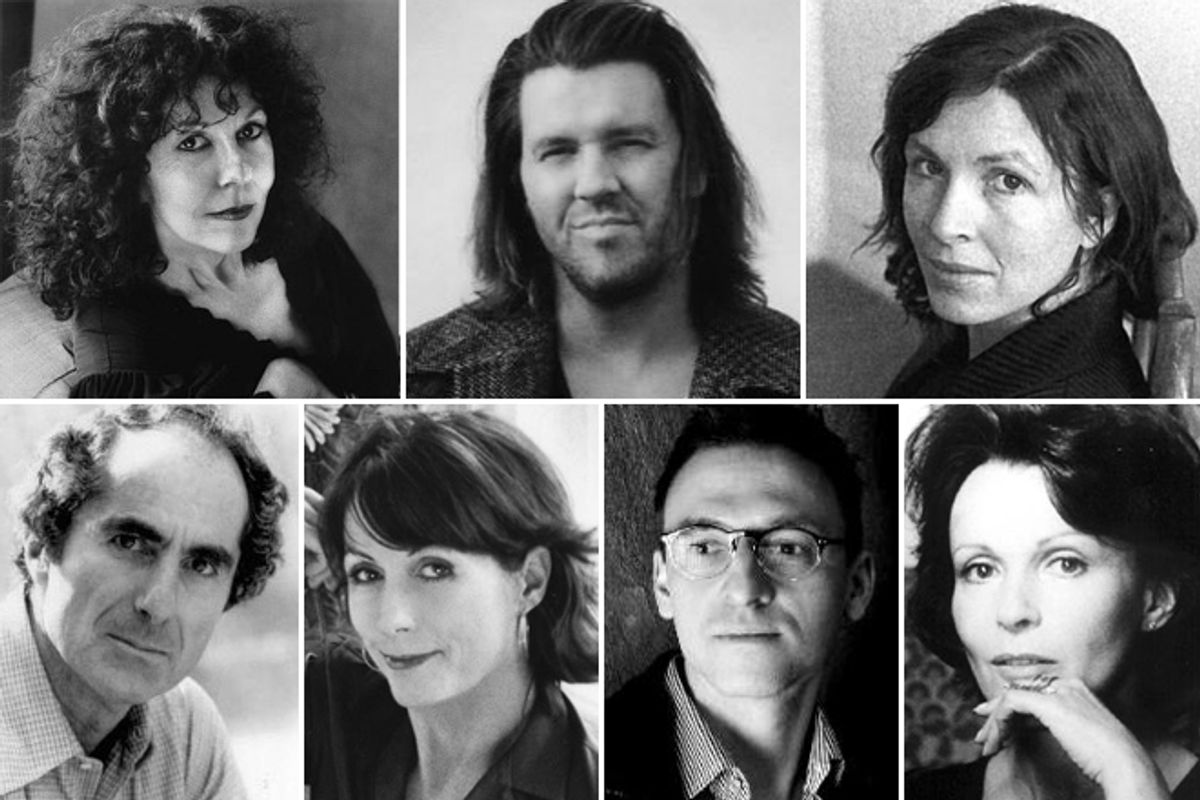

For here it comes, smudged with tears and running a high fever of defensiveness, with a tangle of lingerie on its head, lipstick on its cheek and a tale of outrage in its flailing hand: the breakup memoir. It’s a form of closure that gives new scope to the old line about everything happening for a reason. Allegedly the story of her life, the actress Claire Bloom’s 1996 memoir "Leaving a Doll’s House" was mostly the story of her breakup with Philip Roth, preceded by a swirling Rolodex of celebrities who used to date her — an instant classic of the genre. Bloom’s the kind of writer who likes making lists. Perhaps list-making is the opposite of lovemaking. There are lists of grievances, lists of letdowns, lists of items Roth demanded she return during their divorce (a portable heater merits a mention) and lists of fees he assessed her as their relationship wound down, including a hard-to-interpret $62 billion in damages for her breach of their prenuptial agreement. This tic attains its nadir or apotheosis or (in any case) sublimest self-parody when Bloom, midlist, notes that she only managed to keep “some, [but] not all of my china.” Unusually, we are left wondering. Perhaps the author of "The Human Stain" made off with a teapot. A few saucers. A bijou soup spoon. Here, the reader seems to confront an infinite regress of pettiness. Was it pettier of Roth to take the china, or for Bloom to complain about it? Or was it pettier for him to complain about her complaining, as he later did to the New York Review of Books? Or for her to complain about his complaining as, needless to say, she has?

It is all too easy, of course, to mock the breakup memoirists. Yet I think we should go ahead and mock them. Such wronged tones aren't right for anyone; such raw truths leave us all a little queasy; such husky heart-to-hearts could make anyone snicker. Being in the right may help a breakup memoirist a bit, though being in the right isn’t a strikingly literary condition. (“Writing,” as Roth himself once put it, “turns you into somebody who’s always wrong.”) Wordsworth famously defined poetry as emotion recollected in tranquility, and the capacity to take a cool look at a strong feeling is always vital for a writer. Certainly, excitability is a dependable attribute of bad writing. Is the breakup memoir the opposite of poetry? No one writes them decades after the fact: they represent emotion untouched by tranquility, a storm recollected in a tempest. “[This book] is a letter that one should write to one’s ex but never send,” wrote Jenny Lyn Bader of the New York Times in her review of "Breakup," Catherine Texier’s 1999 memoir of the sexed-up downfall of her literary marriage. A dozen years on, the judgment still haunts this blustery subgenre, where the line between the noteworthy and the wince-inducing is often blurred.

“I don’t have time to disguise this story for the sake of art,” Anastas writes early on in "Too Good to Be True," and though I haven’t double-checked, there’s little cause to doubt the authenticity of the lack of varnish on his memories. The book opens with Anastas the young novelist committing tremulous adultery at the Frankfurt Book Fair, then witnesses him lose, in less than 200 pages, his aplomb, his publisher, his savings and his wife, who was then pregnant with Anastas’ child. The guy who steals her is also a novelist: Christopher Sorrentino, author of the National Book Award–nominated 2005 novel "Trance." Anastas doesn’t name Sorrentino, but then he doesn’t need to. He calls him “the Nominee.”

Perspective, arguably, is another thing Anastas loses. In one chapter, Anastas addresses a letter to the man who cuckolded him (“Dear Nominee”). He mocks the “shoe-polish sheen” of the Nominee’s hair, recounts a few times when the Nominee was a bit of a prick to him and sardonically quotes from the Nominee’s Wikipedia page, while also acknowledging that “my son is crazy about you." Some of his jeers miscarry: “Let’s go back to the night you first groped my wife on the dance floor in your rental tux.” It’s an unstable and slightly upsetting performance, if an absorbing one. Elsewhere, Anastas recalls indignities related to the loss of his wife only by how discomfiting they are to read about. His father turns out to have been a Greek-American New England bohemian who saluted friends (there’s no way around this) by dropping his pants and mooning them: “No one … should have to contemplate the furry pucker of his father’s asshole in the window of a car, or anywhere else … It is like seeing your own death. Actually, it’s like seeing your own death and staring at your father’s asshole at the same time.”

Cringeworthy frankness isn’t an incidental feature of the book. "Too Good to Be True" takes its title from a nickname Anastas was given at a hippy sanitarium his mother repaired to during a bout of depression when he was a child, and it strikes him as the root of what’s gone wrong with his adult self. “I am lost and broke because I have tried to be TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE,” he says. Thus: “Will being TRUE instead reverse the losing trend and set me free?” The memoir is a bet that the answer will be yes. This is why Anastas doesn’t bother with most of the felicities of artistic goodness and instead gives us an intimation of mortality in his father’s rectum: Because if it’s not too good (no argument there) it might just be true. As an autobiographical method, it’s self-consciously anti-literary. Maybe it would have worked better if Anastas had told the story of how he got so poor, about which he keeps quiet in a way I’m tempted to call artful, as implacably as he tells the stories of his marriage, literary problems and disappointing dad. I put the book down feeling he’d been evasive under his paraded candor, or maybe just confused truthfulness with explicitness. It’s a funny kind of artistic crisis when the only bullshit-free zone left is an asshole.

Still, "Too Good to Be True" wasn’t hard to get through. Anastas is a skilled enough writer that you enjoy the memoir even as you qualify your sympathy for the memoirist. There’s no such luck with Rachel Cusk’s 2012 "Aftermath," another account of divorce, which is far too good to be readable: an unyielding travesty of literariness set in “the heart of marital darkness.” Whether that makes Cusk Kurtz or Marlow in her mind is hard to tell, as she never gets around to explaining why she left her husband. Purely in terms of prose style, I’d say she’s more like Dennis Hopper in "Apocalypse Now," who can’t ask the time without blurting out a stanza of “The Hollow Men.” For Cusk writes with a high seriousness that never stops making her look silly. Where does she find the energy, you wonder, to write this badly? As well as Conrad’s novella, she compares her marriage to warfare, the Oresteia and the sack of Rome, and routinely dares heart-sinking flourishes like “her amniotic atmosphere” and “the bloodshed of relationship” — the dropping of that second “the” somehow assuring the vulgarity of the idea. For the most part her syntax is so twisted and her drift so oblique that you don’t really know what’s going on. Weirdly, though, as Cusk ponders “the weave of life knotted into madness” and other topics, the same questions preoccupy her as did Anastas: “Unclothed, truth can be vulnerable, ungainly, shocking. Over-dressed it becomes a lie.” This is on Page 4, before you realize quite how thoroughly she intends to tart up the goods.

“Form is destiny,” Cusk writes, and maybe it is. Anastas takes the pants off the truth, Cusk gets it up for the ball, but it’s telling that these aesthetic near-opposites both treat literary form as a game of dress-up with the facts. They seem to think that rough truths can only be rendered in coarse prose, that refined feelings require verbal finery. They don’t see the difference between style and stylization. When I was younger and more nervous about casualness in writing, I had a hard time with David Foster Wallace. I thought his prose style’s simulacrum of sloppiness (the run-ons, the played-up tentativeness) was a way of shirking art’s prime duty, which was to take a stand for form. But channeling your “brokenness” in a novel is the opposite of stylizing it in a memoir; writing "Infinite Jest" because your girlfriend dumped you is about as strong a stand for form as can be taken. Just think: Wallace could have brought his brokenness to a museum instead. What would the exhibit have been called? “Oblivion” is a bit too bleak, and “Everything and More" a bit too sarcastic. “Picked-Up Pieces” has the right weight of irony, though Wallace was never one for Updike. “Fifty Shards of Dave"?

Shares