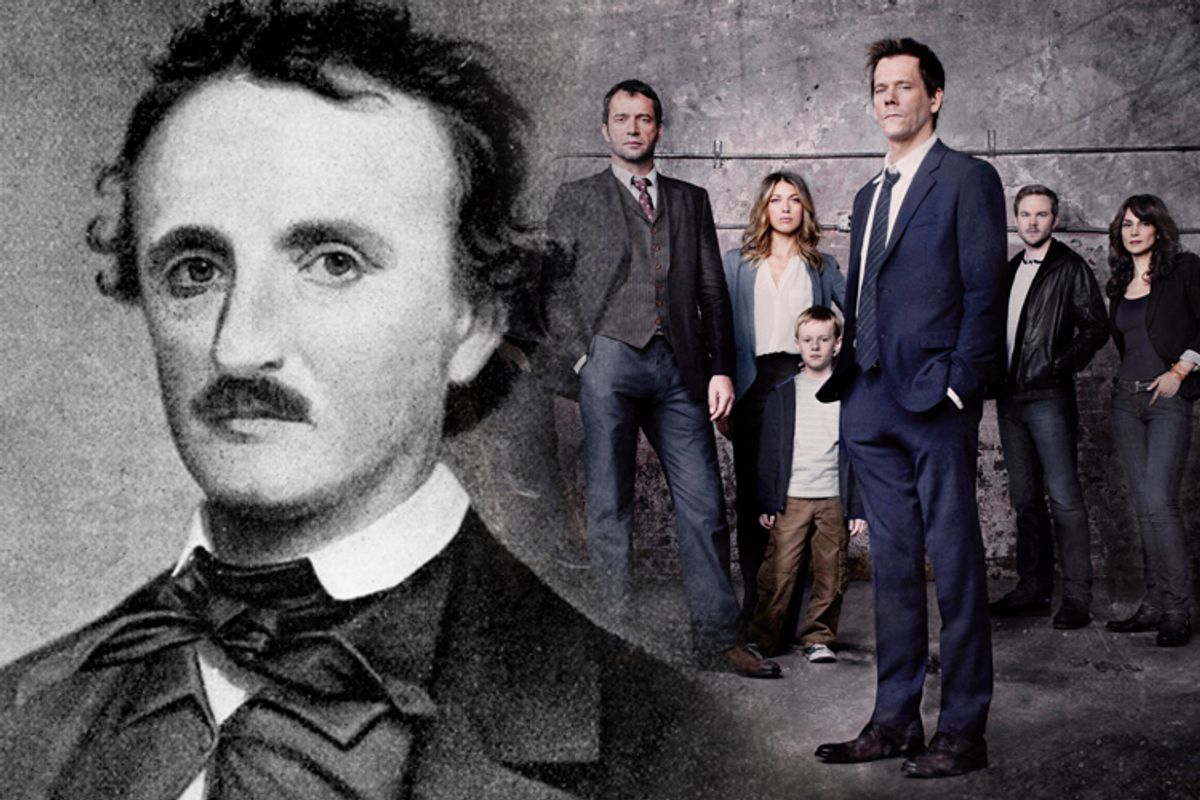

Poor Edgar Allan Poe! His life provides plenty of cause for that exclamation: orphaned at 2, raised by an unsympathetic godfather, shuttled off to military school, half-starved trying to make it as a writer and editor during an economic depression, bereaved by the untimely death of his child bride and troubled by alcohol -- all of this misery culminating in Poe's 1849 death under mysterious circumstances in Baltimore. But as if such injuries weren't enough, now comes the insult of "The Following," an incessant tintinnabulation of shopworn thriller clichés in the form of a new one-hour dramatic series on Fox.

The premise of the show, which is the work of Kevin Williamson ("Dawson's Creek," "The Vampire Diaries"), concerns a serial killer who, while incarcerated for his past crimes, directs a network of worshipful acolytes to carry out further atrocities. The villain, Joe Carroll, purportedly murdered his victims as a "nod" to Poe, his "hero." Carroll's specialty is gouging out young women's eyes -- you know, on account of all the "eye symbolism" in "The Tell-Tale Heart" and "The Black Cat."

Carroll, described as a "professor of literature," is supposed to be an expert on Poe, as well as the author of a novel, "The Gothic Sea," that completes the story Poe was working on when he died. "The Following" features several flashbacks to Carroll in the classroom, teaching in that hilariously reductive style, universal to TV and movie pedagogy, consisting exclusively of trying to decode the author's "message." "Poe's chief principle," Carroll declares to a roomful of rapt students: "insanity as art." Furthermore, he (nonsensically) continues, "This is the Romantic period. Death is about theme, mood, motif, emotional aesthetic."

Other Poe-related mishegoss in "The Following": a woman who strips in a police station, revealing lines from Poe written all over her naked body, before stabbing herself; the obligatory Roomful of Crazy, in this iteration, a decrepit tract house where kinky Carroll followers have been holed up, scribbling Poe quotes and illustrations all over the walls; and a guy wearing a creepy Poe mask setting fire to the critic who trashed Carroll's novel. (Poe buffs will laugh at that one, given the author's reputation as a notoriously harsh reviewer.) Carroll, when questioned on his followers' crimes, explains that he is writing a "sequel" to a bestselling book about his case by Ryan Hardy, the burnt-out FBI agent who caught him the first time around. Ryan is the series' hero.

Poe may be the father of American horror fiction, but he would surely protest at being implicated in this feeble, derivative, dishonest tripe. "The Following" presents an image of his literary intentions and methods that could not be more wrong. While some of Poe's characters are indeed insane, he did not equate insanity with "art." To the contrary, "The Philosophy of Composition," Poe's famous essay on how he wrote "The Raven," promises to demonstrate the supreme rationality of his creative process. He avows that "no one point in ['The Raven's'] composition is referable either to accident or intuition — that the work proceeded, step by step, to its completion with the precision and rigid consequence of a mathematical problem." And, believe me, he shows his work. Sure, the essay suggests a certain amount of OCD, but nothing that remotely resembles the sociopathic, homicidal ecstasy evinced by Carroll.

"The Following" goes on to portray one of Carroll's former students and future victims responding to the professor's questions by dreamily murmuring, "Poe believed that art is about beauty and nothing is more beautiful than the death of a beautiful woman." (Say what you will about today's female English majors, they would not let that concept pass unchallenged.) This, too, misrepresents Poe's ideas. Poe wrote, "Beauty is the sole legitimate province of the poem," which cannot be conflated with "art" since he made separate provisions for prose. Furthermore, Poe described the death of a beautiful woman as the most "poetical" subject available, not because it is "beautiful" but because it is sad. Grief -- something Carroll and his groupies never experience because they're nihilistic, inhuman loonies -- is what gives poetry its profundity in Poe's view.

These may sound like quibbles, but they underline the profound contrast between Poe's soulful version of horror and its degraded present-day descendant, the serial-killer narrative. By rights, we ought to be witnessing the late, decadent period of the serial killer motif, when there's nothing new to say and the borders begin to crumble just before everyone decides we're sick of the whole thing. We've even gotten to the point where we have a meta version in the Showtime series "Dexter," about a serial killer who preys only on other serial killers. Yet the fictional serial killer shows no signs of withering away.

As for "The Following" it could serve as Exhibit A in demonstrating the bankruptcy of this type of fiction. While the narrative pretends to condemn and recoil from its serial-killer villain, it covertly encourages us to revel in his powers. James Purefoy, a British actor best known to American audiences for playing a handsome, swaggering, alpha-male Marc Antony in HBO's "Rome," is only slightly less magnetic here. He is sleek and well groomed, despite being confined to a federal penitentiary and orange jumpsuits for the rest of his natural life. With his plummy accent he addresses everybody in the same buttery, avuncular manner -- although with the FBI agents he's just being sarcastic. (Taunting ranks high in the skill set of every cinematic serial killer.) Carroll has the ability, from behind bars, to mesmerize an untold number of ordinary citizens, persuading them to kill themselves and others in various outlandish ways, and somehow enabling them to get the drop on experienced law enforcement officers over and over again, all in pursuit of ... what? Just bein' evil, I guess.

By contrast, Hardy, Carroll's drab nemesis, has a drinking problem, a pacemaker and a life in shambles. (He's brought back on the case because, as a voice on the phone barks, "No one knows him like you do!") Played by Kevin Bacon, Hardy looks wan and gristly, as if he'd been chewed for a while by someone who ended up spitting him out as inedible. Sometimes he musters the vim to snap at a puppyish junior officer, but mostly he just stares haggardly into the middle distance. Next to Hardy, Carroll radiates health, potency and self-confidence. He is always, to summon yet another cliché, 10 steps ahead of everyone else. Given that fantasies of mastery are one of American pop culture's favorite enticements, the invitation to identify with the glamorized bad guy here is impossible to miss.

Like an anti-porn crusader lingering over the (shocking!) details of the material that offends her, the serial-killer genre, with half-pretended revulsion, offers up lavish interludes of sadistic violence. In order to produce the same extreme response, the ingenuity of the cruelties depicted in books and on film has escalated over the years. Not long ago, I read a novel in which the killer ... But, I'll spare you that. Suffice to say I was freaked out that the author (a state's attorney!) could even imagine such things, and now every time I fly I fret about being cooped up in a metal tube with dozens of people who regard this stuff as a fun, fast read.

Violence in popular entertainment is usually discussed in absolute terms: Either you think it should be reined in quantitatively or you defend it in blanket terms, as a matter of free speech. This bogus polarity obscures an important question: How is it used? Eyes are gouged out in "The Following" because the mutilated female corpses (all young and pretty in life) make a ghastly spectacle and enable Carroll to torment Hardy with talk of severing the victims' ocular muscles one by one. Eyes are gouged out in "King Lear" to indicate that the play's social order has descended to sub-human brutality as a result of the main character's refusal to see the truth. It's the same violent act, but in the latter case it is replete with meaning and induces an elemental despair, while in the case of "The Following" it's just gleefully lurid.

The violence and horror in "The Following" serve to flaunt the fiendish dominance of Carroll, a dominance that only looks more impressive when juxtaposed with the wrung-out Hardy and his inanity-spouting colleagues. (Someone actually says, "I read your file. I know you don't play well with others.") While the works of Edgar Allan Poe do feature death, murder and insanity, he uses these elements of the human experience in an entirely different way. Poe's mad narrators fight against their insanity. His murderers, like the narrator of "The Black Cat," lament their "final and irrevocable overthrow, the spirit of perverseness," and are compelled to betray themselves. Death is not beautiful; it strips them of the people they love and leaves them undone.

The horror in Poe's fiction, for all that it may share a ghastly detail or two with the carnage in "The Following," is rooted in helplessness not power. Madness is terrifying. It overtakes Poe's narrators, compelling them to do what they know is wrong. Guilt gnaws at their composure, so that even those who have committed crimes are hounded by them. In the most overtly sadistic scenario in all his tales, "The Pit and the Pendulum," the perspective is locked onto the victim, strapped beneath a swinging blade; his tormentors are nameless, faceless, absent and in a way insignificant. They might as well be life itself; as Poe knew, there are few things more merciless.

This is why "The Following," with its thinly veiled infatuation with omnipotent, amoral killers, has no right to invoke Poe. Beneath the gothic trappings of his verse and tales is the truth of human life, rather than a callow, sub-Nietzschean fantasy about casting off all moral restraints. (In a passage Carroll reads from his novel, "Good and bad no longer existed. It was all degrees of evil now.") Poe never showed much interest in evil, and his fictional universe is never divested of moral law. Life as he sees it is fragile and filled with loss. Our will and reason may be capsized in spite of how fiercely we cling to them, and we may end up doing things we will regret forever. That is the real heart of the horrors Poe wrote about, and heart is the operative word.

Shares