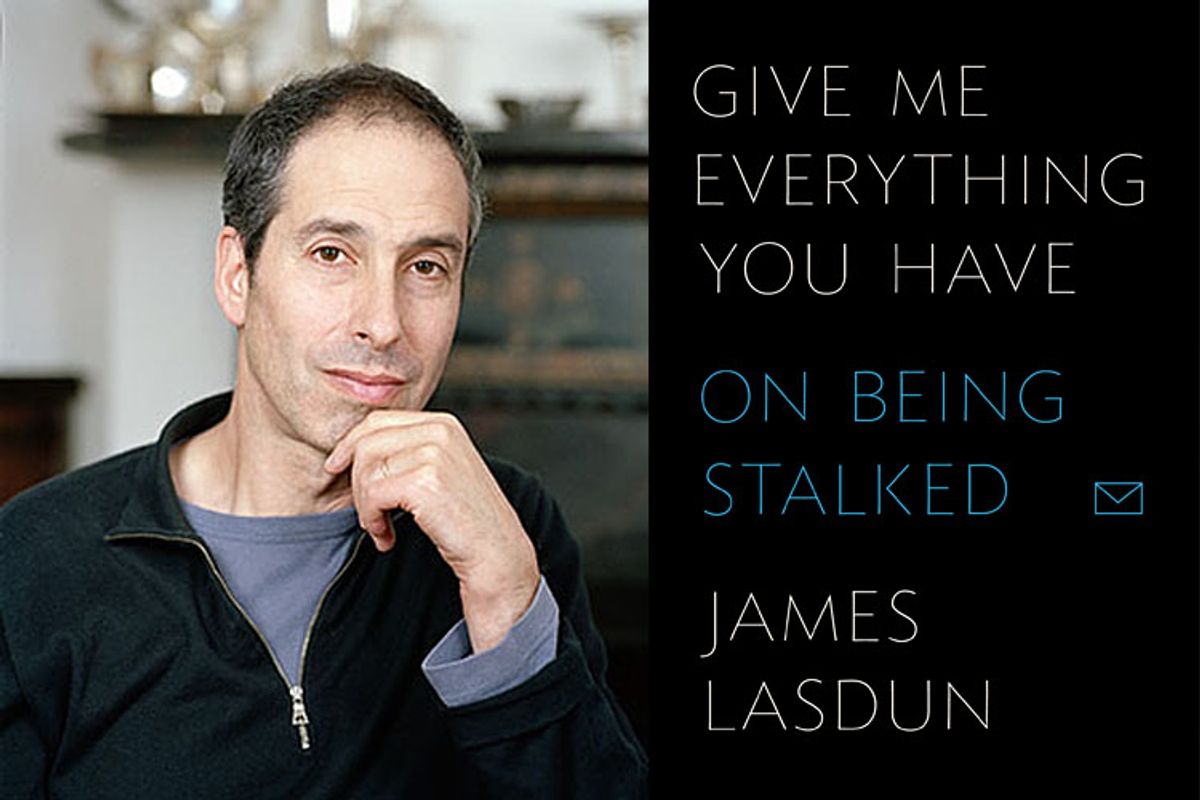

With its eerie, pristine prose, James Lasdun's fiction distills the anxieties of contemporary life to their mythic core. In his remarkable 2002 novel, "The Horned Man," an academic estranged from his wife goes quietly mad while serving on his college's sexual harassment committee, imagining that the department's most legendary womanizer is secretly living in his office and sabotaging his life. Take a writer like this, one who specializes in the surreal, inward spiraling of paranoia, and make him the target of a clever stalker: It sounds like the premise of a James Lasdun novel, right? However, "Give Me Everything You Have: On Being Stalked," Lasdun's new book, is not a novel, but a memoir.

In the mid-2000s, Lasdun struck up a chatty email correspondence with a woman who had taken one of his graduate creative-writing workshops two years earlier. He remembered her work as exceptional, and the rough draft of the novel she sent impressed him, so he put her in touch with his agent and an editor who might help whip the draft into shape. Her novel, about an affluent Iranian family living in Tehran during the fall of the Shah, was autobiographical. The two writers met for coffee during one of his visits to New York City, and Lasdun was struck by the "reticent" demeanor of the friend who had always seemed so lively in her emails. "There was something canceled or hidden, somehow, about her bearing; a strange irreality in her presence across from me at our lacquered pine table, as if she were absent in all but the most literal, mechanical sense."

Over time, their correspondence made him uneasy. Mildly flirtatious banter -- a not uncommon divertissement in email exchanges between people who rarely or never see each other -- led to her recounting of "salacious gossip," purportedly originating from other workshop members, about Lasdun and herself. When he mentioned a forthcoming cross-country train journey, Nasreen, as he calls her, playfully offered to smuggle herself into his sleeper car. Lasdun responded by ignoring the innuendo and making frequent references to his happy marriage. Finally, he realized that "something more explicitly discouraging than a mere tactful silence was going to be required of me."

Nasreen, who at first seemed to accept Lasdun's rebuff gracefully, became gradually unhinged, pelting him with "unstoppably amorous communications, often a dozen or more a day," as well as forwarding gossipy private emails from other people and correspondence related to a sexual harassment lawsuit she was pursuing at her workplace. He stopped writing back -- temporarily he told himself -- and then left the country for several months on a research trip with his family. He never communicated with her directly again.

Enraged, Nasreen continued her digital assault, filling Lasdun's email box with ravings. She accused him of sleeping with another student, or several other students (though not herself), of using her private emails in his fiction, of engineering a rape that allegedly occurred before they even met and of participating in a conspiracy to steal her work and sell it to other Iranian women writers who were publishing at that time. Many of these messages contained violently anti-Semitic abuse. (Lasdun is a Briton of Jewish descent.) She began sending similar emails to Lasdun's agent, the freelance editor he'd referred her to and his employers. (Like a lot of writers, Lasdun takes short-term teaching jobs at various colleges.) She posted harsh reviews of his books on Amazon and the social-networking site GoodReads, as well as nasty comments, whenever possible, on every article Lasdun wrote.

Lasdun provides plenty of excerpts from Nasreen's emails (finally validating her old delusion that he was raiding her life for material), and they are so manifestly the work of an emotionally disturbed person it's hard to believe that anyone took them seriously. Yet, some apparently did, among them an NYPD officer, who offered Lasdun a little desultory help, and the director of a program where Lasdun was teaching. These two men were briefly willing to entertain what strikes me as the most preposterous of Nasreen's charges: that he had somehow stolen and resold her work. (The willingness to believe such fantasies seems to come from the popular misconception that the most important thing about any piece of writing is its ideas or premise, rather than writing itself.)

Despite its lack of material impact, Lasdun was tormented by Nasreen's campaign to "ruin" him. Even when nobody believed her crazier and crazier invectives, he still felt that he was tainted by them. "Intrinsic to the very nature of Nasreen's denunciations and insinuations," he writes, "was, as I began to understand, an iron law whereby the more I denied them the more substance they would acquire and the more plausible they would begin to seem." An author whose work is often likened to Kafka's, Lasdun found himself in a notably Kafkaesque situation, beset by an unseen, tireless, irrational accuser and never entirely sure how innocent he appeared in the eyes of those around him. He became irritable, insomniac, preoccupied, depressed.

It's easy to view the sensitive Lasdun's response to this situation as deriving from the two banes of his dual background: English embarrassment and Jewish guilt. The shame he felt at being associated, however unjustly, with Nasreen's sordid rants was compounded by a compulsive self-scrutiny: Wasn't he initially flattered by her crush on him? Didn't he cut her off rather abruptly? Wasn't there a troubling power imbalance -- age, gender, ethnicity -- in their friendship?

Here, the reader may feel conflicted; If Lasdun is engaged in an extended, self-inflicted form of victim-blaming, the result of all this introspection remains an enthralling and thoughtful book. He contemplates his ordeal while visiting D.H. Lawrence's burial place in Santa Fe, while reading Patricia Highsmith's "Strangers on a Train," while remembering his youthful infatuation with "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight," a story whose almost perfectly virtuous main character he identifies with. It's only when he attempts to grapple with Nasreen's anti-Semitism by traveling to Israel in what's meant to be the climactic portion of the book that these inquiries fizzle. The political and rhetorical thickets of the Arab-Israeli conflict will not bend to his method; they remain intractably exterior, while his forte is rummaging around in the basements and sub-basements of the psyche.

"I have a strong, vested interest ... in claiming that Nasreen was fundamentally sane," Lasdun writes near the end of "Give Me Everything You Have." "I want to hold her responsible for her behavior." But he has to admit that if she were simply, merely mad, then his story would become "for literary purposes, less interesting." He'd rather believe that whatever unhinged Nasreen served to liberate a toxic element that lurks in most, if not all human beings. This would give Nasreen moral stature, make her a more interesting villain. It would also, though he doesn't quite acknowledge as much, endow his own suffering with more significance. If the cause of his misery and self-doubt was "just the chaotic by-product of chemical imbalances and misfiring synapses," then it is "essentially meaningless." As for insisting that the tribulations people live through amount to more than an accident of biology, well, that's essentially what writers do.

Shares