Like many modern people -- especially the fictional ones who serve as the narrators of novels -- Paul Lohman is nettled by newfangled affectations, particularly those of posh, trendy restaurants and their habitues. In an irritable, self-righteous tone familiar to anyone who reads Internet comments threads, he snarks about the place his brother has picked for the meal that gives Herman Koch's novel, "The Dinner," its title. Restaurants are not the only thing that gets on Paul's nerves. While he and his wife, Claire, wait for Serge and his wife, Babette, to show up, Paul ruminates on the humiliations inherent in shaving: If you do it before a meeting, you betray overeagerness, but if you don't you seem lazy or even sickly. "No matter what you do, you're not free."

Also on the list of things that bug Paul: the waiter's insistence on elaborately recounting the provenance of every item they order ("Did you notice how he points with his pinky all the time?" Paul hisses to Claire), the "yawning chasm between the dish itself and the price you have to pay for it," and the "vast emptiness" of the plates when they arrive bearing their dainty portions of food.

Then there's his brother, a politician likely to become the next prime minister, but whose habits and personality irk Paul. Serge, who guzzled vast quantities of cola as a youth, now -- intolerably -- fancies himself a wine lover. Serge has a house in France and frequents restaurants like this one, where he's greeted personally by the owner, except when he insists on popping by places like the nearby "ordinary-people café" favored by Paul and Claire -- although, of course, Serge only goes there to pretend ostentatiously to be a "regular guy."

And what about the son Serge and Babette adopted from Burkina Faso, taken in after they'd had two biological children? Paul suspects there was calculation even in this seemingly generous act, though the couple did it before Serge's career took off. Nevertheless, Paul notes "it looked good" to have the black boy (now a teenager) appearing in family photographs as "living proof that there was one politician who didn't act purely out of self-interest."

The two couples are convening over this dinner to discuss urgent family business. Paul and Claire's son, Michel, and Serge and Babette's biological son, Rick, have gotten themselves into some serious, if initially obscured, trouble. Paul adores Claire and regards his own home life as the definition of happiness: "Happiness needs nothing but itself, it doesn't have to be validated." With Claire, he has an effortless rapport, and the ability to communicate by the tiniest gestures or expressions. Nevertheless, he hasn't yet told his wife what he discovered just before they left for the restaurant. Paul sneaked a peek at a video on Michel's cellphone and learned that their troubles are bigger than he'd thought.

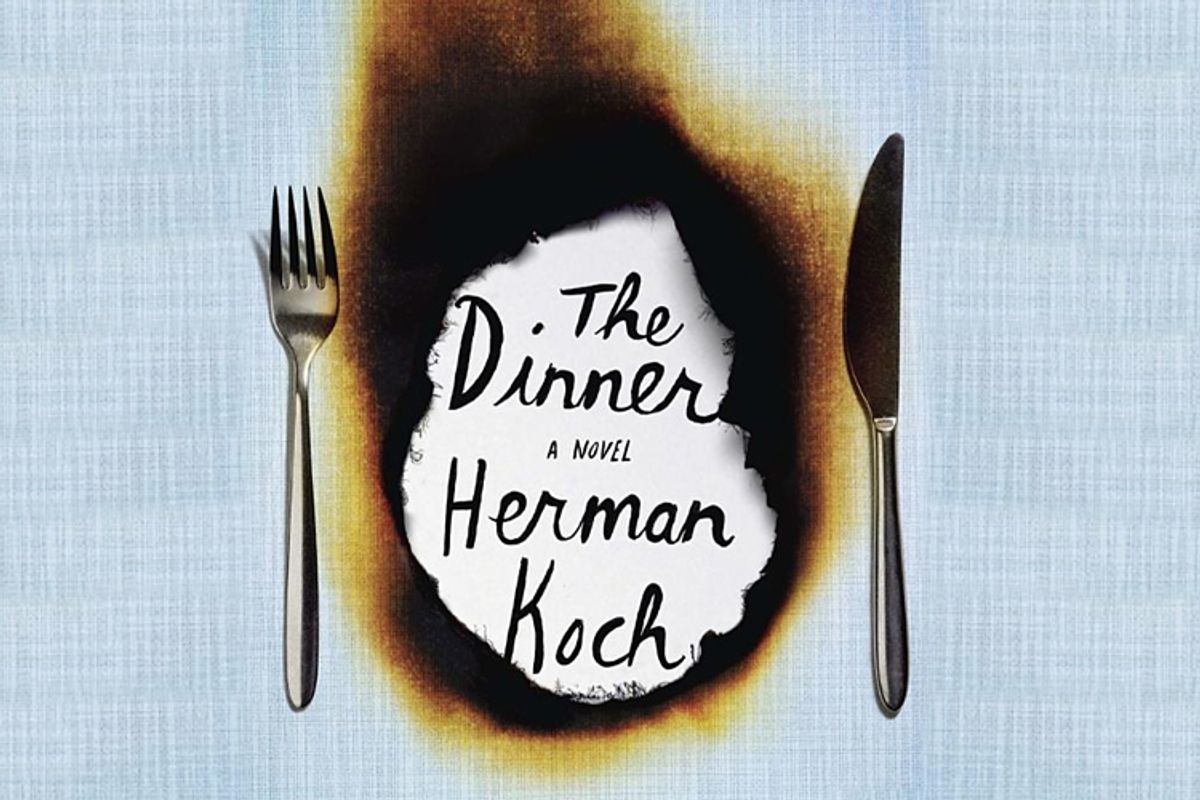

"The Dinner" sold more than a million copies in Europe, where it was originally published in 2009. (Koch is Dutch.) The novel has been called the "Gone Girl" of the Continent, and not without cause: Like Gillian Flynn's bestseller, it's a tale told by an unreliable narrator, full of twists and skillfully executed revelations, ultimately registering as a black parable about the deceptively civilized surface of cosmopolitan, middle-class lives. No people could better epitomize the notion of progressive, enlightened Westerners than the Dutch, whose nation, like its Northern European neighbors, consistently ranks among the world's happiest and most peaceable. Informally, and perhaps perversely, the Dutch also have a reputation for being a bit boring.

Paul would probably concur with the latter criticism, but, then, as the novel proceeds, the reader can't help noticing just how many things Paul objects to: "People who describe entire films," Dutch people who idealize rural France, men who seem overly proud of having a "steady, powerful jet of urine" (compared to his inhibited one) when they stand next to him at a urinal, "morons whose breath stinks like rotten meat but refuse to do anything about it," "hopeless cases who go on complaining all their lives about the nonexistent injustices they've had to suffer," and so on. Sure, most of these features of contemporary life are annoying, and who hasn't occasionally entertained a group of friends with an amusing, Denis Leary-style rant about stuff like that? Commiseration is a bonding ritual.

That inclination to identify with someone who takes a skeptical, even curmudgeonly attitude toward the fashionable, the fancy and the fussy -- whether in cuisine or positions on social issues -- often runs strong in readers; what could be less cutting-edge, after all, than reading a book? Combine that with the natural tendency to trust one's narrator, and Paul starts off "The Dinner" with a heaping helping of the reader's faith. Then, ever so slowly and fiendishly, things go wrong. And to say any more that that would make me a spoiler -- another type of person Paul hates.

"The Dinner" is probably too disorienting and merciless to resonate with a broad swath of American readers. We tend to be less self-critical than Europeans, and (to judge by some reviews of "The Dinner"), a lot easier to confuse. What Koch achieves with his prose -- plain but undergirded by breathtaking angles, like a beautiful face scrubbed free of makeup -- is a brilliantly engineered and (for the thoughtful reader) chastening mindfuck. The novel is designed to make you think twice, then thrice, not only about what goes on within its pages, but also the next time indignation rises up, pure and fiery, in your own heart.

Shares