The American healthcare system is based on gambling. Every day, life or death choices are made based on the perceived odds of success. And for every heartwarming, headline-making story of some brave survivor who beat the odds, there are many more tales of those whose journeys and outcomes have been very different. What’s the price of a wager, in a game nobody ever said was going to be fair? That’s the question at the heart of the story of Sarah Murnaghan — and the complicated issues surrounding her treatment.

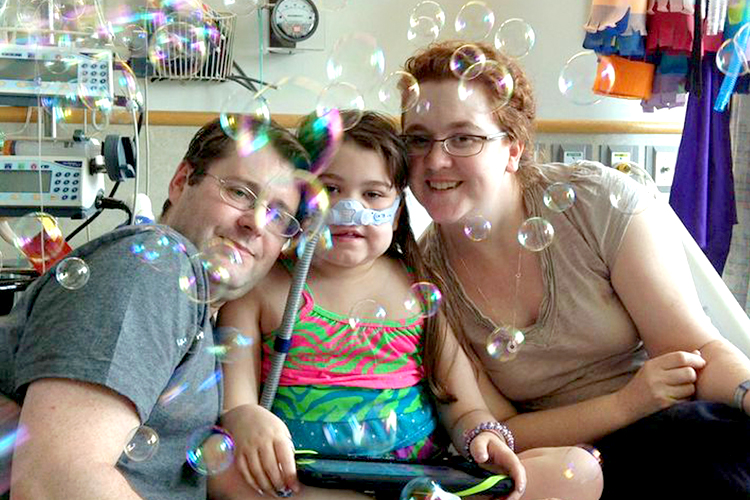

The 10-year-old girl, who has cystic fibrosis, received a lung transplant at Philadelphia’s Children’s Hospital on June 12 after her family won a lengthy battle for her to get on the adult Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network’s list. Her transplant was already controversial, raising ethical issues about who gets priority on organ donation lists, when the news of her family’s legal victory broke last month. But late last week, her story took yet another turn when her mother revealed the girl’s health had begun to “spiral out of control” after the surgery – and a few days later, she underwent a second lung transplant from a new adult donor. Her chest had to be kept open to alleviate pressure on the organs. “Under a bandage, you can see her heart beating, her lungs rising,” her mother said. The girl is reportedly able to take a few breaths on her own now, but she is scheduled for another operation Tuesday to rectify an outstanding complication from the prior surgery.

Murnaghan was facing an all but certain imminent death before her transplant came through. Even now, Arthur Caplan, head of the division of bioethics at NYU Langone Medical Center, says, “Sadly, she faces very long odds of surviving,” and asks, “Given her medical situation, should she have been on the adult list in the first place?” But then again, it’s worth asking why children her age were ever cut off from being candidates for potentially viable organs in the first place (the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network used to keep children on a different list because the size of adult lungs can make transplants difficult, but it’s beginning to change those rules).

Murnaghan’s case has made headlines, but the ethical issues her family and doctors face are common. Treatment is an investment – an expensive one – and stark financial reality and limited medical resources are often at odds with the emotional instinct to save lives. When Lou Reed received a liver transplant recently, critics were quick to point out his age — 71 — and his years of alcohol and drug abuse. Was he less worthy than a 50-year-old non-drinker? What about a 30-year-old drug addict? How do you calculate the value of a life? Clinical trials recruit subjects selectively, looking for candidates who are both sick enough to qualify for the drugs and well enough to tolerate them. (I’m grateful every day I hit that particular sweet spot.) Families battle ferociously over patient “Do Not Resuscitate” directives. As the judge in a 2010 New Jersey DNR court case noted, “Determining what medical treatment should be provided to incompetent or dying patients presents a matter of substantial public importance.”

But what’s infinitely tricky to assess is exactly when someone becomes “incompetent or dying.” On Monday, BoingBoing revealed the story of Janet Freeman-Daily, a Stage 4 lung cancer patient whose insurer rejected her appeal for a biopsy because it was “not going to affect long-term health outcomes.” In other words, if you’re Stage 4, why bother? But as Freeman-Daily, who is in a targeted therapy clinical trial and has had no evidence of disease for five months, now writes, “I’m a perfect example of a stage IV patient who has a good prospect for years of a reasonably active life despite my disease.” And though Sarah Murnaghan’s case still seems dire, it’s worth noting she’s a patient at the same children’s hospital where a year ago, leukemia patient Emma Whitehead was on the brink of death, before a revolutionary experimental treatment totally reversed her disease. She completed second grade a few weeks ago.

Sometimes it works. Sometimes it doesn’t. The process is costly and time-consuming and fraught with heartbreaking losses along the way. As Murnaghan’s story shows, it also comes with agonizing, uneasy questions over who gets to be treated, who get a chance to be saved. And no guarantees, for anybody.