No one had high hopes for the presidential election that just passed and so, perhaps, no one was disappointed. But that dreary slugfest, like any war, nevertheless becomes the most relevant model for how the two parties will fight next time.

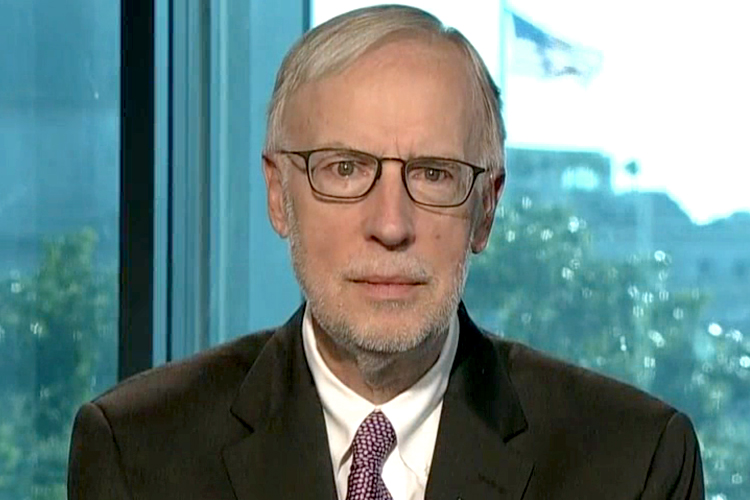

As the Washington Post’s chief correspondent, Dan Balz is one of a handful of old media lions who can still shape the conventional wisdom; as such his new campaign book “Colllision 2012” is as close to an account-of-record as we’re likely to get.

Balz talked to Salon about how the Republicans might recover, what’s right with Washington and why he rarely posts on Twitter. The transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

2012 wasn’t anybody’s favorite campaign, but was it an important campaign?

You’re right about the first part of it. When it finished everyone said, “Good riddance, we don’t want to revisit it and we may not want to read about it. (laughs)

It was an important campaign, or could have been. One of the reasons I used the title “Collision 2012” was to talk about the idea that this was potentially a significant clash of philosophies and government and the economy and that sort of thing, in a way that 2008 wasn’t. 2008 was much more the personality campaign and the inspiration of Barack Obama. This one really was a question of what direction do people want to go, and in that sense it was a big campaign. There were some big things on the table.

My takeaway was that it was a big campaign but often fought out in really small ways.Neither side could figure out a way to create the great debate that everyone claimed they wanted.

Do you see any aspects of it changing how the next campaigns will be run?

Yeah, I do. I think this was a window into the future in ways that some past campaigns haven’t always been. Obviously, things change from cycle to cycle, and I thought some of the changes between 2008 and 2012 were bigger than we’ve seen in past cycles and I do think they tell us something about the future.

Like what?

One, to state the obvious, is the power of social media. Twitter wasn’t a factor in 2008, and we suddenly saw in 2012 how powerful a medium it can be. It’s the new former of conventional wisdom, it’s the new community bulletin board for the political community, it’s an early warning system for campaigns for hurricanes that are developing out in the Atlantic and may wash them away.

We obviously saw it the night of the Denver debate. The story was written on Twitter in the first 30 minutes and reinforced in the next 60 minutes, to the point that a very strong performance by Romney and a very weak performance by the president got locked into all of the discussion about that debate. There were 10 million tweets in the 90 minutes of that debate. So that’s one.

The debates themselves.The parties themselves always say they want to bring this under control, and maybe there will be fewer debates in 2016 than there were in 2012, but I think one thing the debates showed is that they now create a national conversation, and in a sense a national primary, that runs parallel to, and in some ways eclipses, the kind of retail politicking that we’ve gotten used to in Iowa, New Hampshire, and to some extent South Carolina – the earliest of the states.

The debates had as much influence on the shaping of public opinion and the views within the Republican party as anything else that was going on. I always used to think of Iowa as being the place – because it saw the candidates first and closest, it tended to be ahead of the rest of the country. What we saw in 2011, as we were heading to the caucuses, was that Iowa public opinion was moving very much in the same way that public opinion in the rest of the country was moving.

Obviously, in the wake of Citizens United, the role of super PACs is changing politics. Did it change it in a decisive way? I don’t think it did in the general election. I think the super PACs were important and influential in the Republican primaries.

Do you see the PACs not having an influence in the general election just because the Republicans didn’t seem particularly savvy in how they spent a lot of money?

That’s part of it. Also, I think that there was just so much advertising that I think, at a point, it either cancels itself out or it’s the law of diminishing returns. I spent a lot of time in Ohio, and I remember toward the end of the campaign, watching local news on Ohio TV in Columbus, and it felt like there were seven minutes of news and 23 minutes of advertising. The whole imbalance of it was such that I have to think that normal people tuned that stuff out.

You talk about the importance of Twitter, but at least in terms of posting, you’re not active. Any particular reason?

I’m not as clever as most of my friends. Seriously. I’ve got lots of colleagues who tweet wonderful stuff. Karen Tumulty is a master at Twitter. Roger Simon at Politico is a master of Twitter. I tend to be more reserved. I watch Twitter a lot, but I don’t necessarily enter into the conversation.

It’s a common complaint that campaign reporting is boring because the campaigns are so controlled. You probably have more access than most reporters but do you find it boring?

I don’t find it boring, and I don’t have access that goes significantly beyond what most reporters have.

Campaigns are harder to deal with. I was able to get some access during the campaign because they knew I was working on a book, but even that tends to be more limited than it used to be. All campaigns are wary of spending too much time talking to reporters.

I don’t find it boring. To some extent, what I worry about is that we grab for the trivial at the expense of the significant or consequential, even though the significant or consequential is a harder story to tell. There are moments in any campaign that we all seize upon because they seem like a big story at the time, or because they’re tremendously entertaining and yet we don’t do enough with, for example, the changing demographics as a country. How do you tell that story in a way that everybody’s cognizant of the hole that Republicans have created for themselves, or that this country is putting them into?

Those are the challenges in political reporting. We have to find an audience and keep an audience, and you have to write politics in a bright and lively way, but you want to be both smart and clever, but if you have to choose one versus the other, you want to be smart.

It’s hard to do it on the fly; it’s hard to do it sitting on the campaign bus; it’s hard to do it with limited access, but I think it’s one of the challenges of political reporting these days.

You mentioned the demographics story. No one talked about that during the campaign, and it’s all anyone’s talked about since.

It is. I was sort of astonished to see Republicans wake up after the election and discover they had a problem with the Latino vote. This has been staring them in the face for a long time: we have known not just from the recent census, but we have known from the prior census. And the Republicans have not consistently been able to corral a significant and steady percentage of that vote. George W. Bush had more success than others, and his brother Jeb did pretty well, but they have been the exception and not the rule. Republicans for whatever reason have continued to cling to the idea that because some of their philosophies sync with the Hispanic community, they will be able to find a bigger audience.

But you could argue that one of the most damaging things to happen to the party were the debates about immigration during the primaries and how it hurt Romney. Then to wake up after the election and saying, “We have to do something about that” – it’s like they spent 18 months making the problem worse, and then said, “Oh my goodness, we have a problem.”

Is there any way to fix the problem except passing an immigration bill?

Yes. The immigration bill is not the be-all and end-all for Republicans within the Hispanic community. In some ways, it’s a door-opener. It creates an opportunity for a longer conversation between Republican candidates and Hispanic voters. It doesn’t completely solve the problem, it just prevents it from being worse than it is. But they’ve got to figure out either how to make their philosophy either more relevant or more appealing to Hispanic voters, or recognize that there are things Hispanic voters are looking for that they’re not offering, and they’ve got to figure out a way to do it, whether it’s through economic policies or social welfare policies.

The other problem you have is that you’ve got a party badly divided on the question of immigration, and as long as that’s the case, every time you have a Steve King, the congressman from Iowa, make the comments that he did recently, it sets back the whole party.

What are the other questions you’re asking yourself about 2014 or even 2016?

For 2014, I think that the big question is “To what extent, if any, does it tell us something important about what could happen in 2016?” Midterm elections sometimes predict the future, but very often they don’t. The electorates are quite different in the midterm elections than in the presidential years. One of the reasons the Republicans had so many problems in 2012 was because they thought that the 2010 electorate, which was older and whiter than the 2008 electorate, was closer to what they were going to have in 2012.

We’ll look at 2014 and we’ll do a lot of interpretation of it, but I think we’ll have to do it with a certain amount of distance and skepticism. In 2016, I think the issue, particularly for the Republican party, is to what extent do they have a vigorous debate about who they are as a party and where they want to go. Are there candidates to run for president who are able, in the way Bill Clinton did in 1992, who are able to think through the assets and liabilities of the modern Republican party?

What policies need to be changed or tweaked or spoken of less, and what things do you talk about more and how do you talk about it? It could be a really fascinating contest for the Republican nomination in 2016. If the party is lucky, they will have that. It could also be a wrenching discussion; it could pit one faction versus another, but a skillful candidate is the one who finds a way to bridge those divisions within a party.

Talking strictly about policy, do you have a picture in your mind of what a winning Republican looks like in 2016?

I don’t. They have to work that out. They have to find a way to develop an economic policy and message that doesn’t appear as though it is tilted towards the wealthy, that is equitable across all income groups and is sensitive to the anxieties and aspirations of the middle class.

There’s some people in the party who are beginning to try to think about this, but they’ve had a particular approach to economics. And it’s not clear that it’s as salient as it was 10 years ago, or 20 years ago. They’re not going to throw out the idea that they’re for smaller government or lower taxes, nor necessarily should they. There are a lot of Americans who, at least in a general way, believe in both of those, but it has to be done in a way that resonates broadly with people, and particularly with the people they’re not getting.

To win an election, you’ve got to do two things. You’ve got to energize your base as much you can, but you’ve also got to find those voters who keep you from being a 46 or 48 percent candidate and turn you into a 50.1 candidate.

It’s funny how you said earlier that the debates were so important, since the primary debates weren’t necessarily marked by any sort of particular disagreement. It was more like a presentation or a spectacle.

Yeah. They were reality TV for political junkies. The reason I say they were influential is they obviously drew an audience of, among others, people who were voting in the primaries and the caucuses. And they did tend to be personality-driven.

When you have eight or nine or 10 people on the stage, you rarely get a deep discussion of policy—let’s be honest. For one, the debate hosts generally are not looking for that. They want clash and battling back and forth and people dusting one another off, but there are other ways that you get to that.

If you’re debating every other week, There are opportunity costs. One is you’re spending less time with voters, which means you are less in touch with what’s on the minds of real people.

I’ve always thought that one of the values of Iowa and N.H., though they’re not at all representative of the country at large, is that it forces candidates to listen to other people, and to be presented with a view of the world that they might not otherwise get, and that can affect their thinking.

The other thing it does — we saw very few serious efforts at laying out a philosophy or a particular policy. Often there’s very little as boring to journalists and maybe readers as a story about a speech about a policy X. But when people get elected, the sort of starting point for their administration’s agenda can be that series of speeches. Time and effort goes into those. And if you’re spending all of your time debating, you’re thinking about A) how can I survive without making a fool of myself and B) what’s the sound bite I can utter that will capture attention. The incentives and rewards are sort of in the wrong places to sort of get that from people.

You don’t appear in “This Town.” Why not?

You’d have to ask Mark that. I don’t know. Maybe I’m not a “This Town” kind of guy.

Do you have any thoughts on how the culture that book describes has influenced elections?

One thing we know is that people outside of Washington have a very low regard for Washington. And Mark’s book brilliantly captures the culture of one part of Washington, and the part that I think the people outside dislike the most.

I don’t know how that has affected campaigns. The campaign industry is a real industry. It’s a year-round, fulltime industry, that is, in many ways, divorced from the governing process, or, to some extent, has infected the governing process.

It’s the permanent campaign intersecting with partisan divisions in governing and it creates this system that we have now, which the two parties can’t work out some of their differences in order to get some of these things passed. Ultimately, I think all of that has a corrosive effect on voters and I think it’s why we see so much disgust and anger with Washington.

Can you tell us anything about Washington that would make anyone from outside Washington have a higher regard for it?

Well, I think there are a lot of people here who genuinely do want to get some things done. There are a lot of people who get into politics for the right reason. I’ve covered politics obviously for a very long time, and you can’t cover politics if you’re so cynical about it or loathe the people who are in it. There’s a lot of aspects of politics and campaigning that I don’t find attractive, but I think that in order for democracy to work, you’ve got to have elections and you’ve got to have debate, and I think there are people who want to do that. But we’re in a period in which it’s harder to do that than it used to be. The incentives are all in the direction of trying to win the next election, because if you win the next election, maybe you’ll be in power. But what we’ve found is being in power doesn’t mean you have real power. And so I think that’s the next order question that has to be addressed.