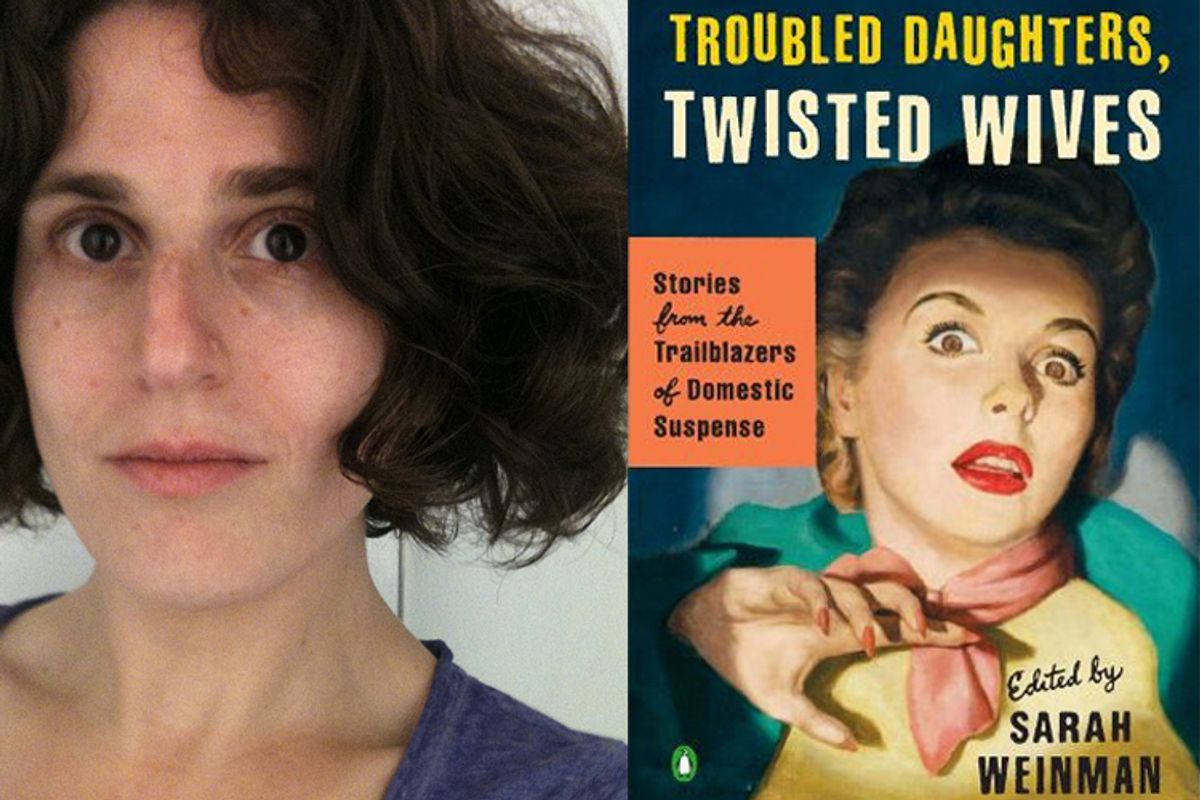

Few people know more about crime fiction than Sarah Weinman, a publishing journalist and critic who specializes in searching out and celebrating the best novels of mischief and mayhem. (Just this year she's pointed me to such artful page-turners as A.S.A. Harrison's "The Silent Wife" and Kelly Braffet's "Save Yourself.") Now Weinman has edited an anthology of her own, "Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Stories From the Trailblazers of Domestic Suspense," which collects short stories by a lost generation of women. These writers spun unsettling tales set in kitchens and bedrooms, where the tension grows out of our closest -- and most dangerous -- relationships. A couple of them, Patricia Highsmith and Shirley Jackson, have held onto their followings, but the rest, despite their past popularity, are in danger of vanishing from memory. These are the predecessors of such psychologically probing crime novelists as Laura Lippman and Gillian Flynn, and thanks to Weinman, they're poised to reach a bumper crop of new readers. I met with Weinman recently to find out more.

Is domestic suspense an established genre or subgenre, a term that people in publishing use routinely?

When I started using the term, I thought I had made it up. Then more recently I learned there had been other critics and websites that used it, one website in particular, called Mysterious Matters, which is run by a pseudonymous and (I believe) male editor at a small press. He's very steeped in the books of a lot of the authors who are in this anthology. He used the term "domestic suspense" in 2009. I must have seen it and not realized it.

Or great minds think alike! How did you first start thinking about it as a subgenre?

I was commissioned by [the literary journal] Tin House in 2011 to write a piece for an issue with the theme "The Mysterious." I'd been reading a few of the authors in the anthology, especially Elisabeth Sanxay Holding, because a niche publisher called Stark House Press had been reissuing her books, and Raymond Chandler had called her "the top suspense writer of them all" in a letter to his publisher. I thought, who is this woman? Then I read the reissues and thought they were great -- and strange. Very [Patricia] Highsmith before Highsmith.

I picked her and Celia Fremlin's "The Hours Before Dawn," which the more I talk about it the more I realize it's one of my favorite suspense novels. It was first written in 1958, and it features a woman who has two young kids and just had a third infant. She's clearly in postpartum depression but they didn't use the word back then, and she's got this husband who's a complete condescending mansplainer.

I also went back to an earlier work called "The Lodger" by Marie Belloc Lowndes, which was a prototype of domestic suspense. It's about a couple that once was middle class but has fallen on hard times, and Lowndes really paints the desperate straits they're in. They take in a lodger, who's weird, keeps odd hours, wants to be shut up in his room alone but then he's out and about at night, and meanwhile as they're dealing with their internal drama, women are being butchered in the streets. There's definitely a Jack-the-Ripper element, but also this claustrophobic theme of how to survive and hold a marriage together.

How did that essay lead to a bigger project?

What I found was that there was a whole generation of women writers, mostly working in the period between World War II and the dawn of women's liberation in the early 1970s. They were critically acclaimed, many won Edgar awards or were made grand masters by the Mystery Writers of America. They sold very well and were published in hardcover, whereas a lot of their male counterparts, who are now considered part of the crime fiction canon or are in Library of America, they were only published in paperback. So, what happened? I wanted to know more about them.

I was complaining to a Penguin editor about this, how these women weren't in print anymore, and he said, "There may be an anthology in this."

How would you define domestic suspense?

I freely acknowledge that some of the women in this anthology, such as Dorothy B. Hughes ("In a Lonely Place") and Vera Caspary ("Laura"), might be classified as noir. But they were also very concerned in their work and life with matters of where women fit in. Hughes was writing novels and then quit for 11 years.

Because she was caring for invalid relatives, wasn't it?

She had an ailing mother, and she also had children and grandchildren. So she was squeezed. She basically did not have the emotional space to work on fiction. She still reviewed extensively, though, and eventually she produced a biography of Erle Stanley Gardner.

In Caspary's case, she was kind of a badass. She was always writing about independent women. She didn't get married until she was 50, and then it was to this producer with whom she'd had this tumultuous bicoastal affair. She was waiting for him to leave his wife. At the same time, they were involved in social causes. She had an interesting life. In "Laura" the book [as opposed to the 1944 Otto Preminger movie], Laura is really trying to stand up for herself, saying, "No, I am having a career. Why are all these men trying to define who I am and what I do? I want to define myself." Seventy years later, that book still works.

The two main strains of crime fiction are hard-boiled and noir at one end and cozy at the other. But there's this in-between terrain.

What are the criteria that you used in picking the stories?

I wanted stories that started in the home. It's the idea of violence among the most intimate: husbands and wives, mothers and children, siblings, and also caregivers. The last story, by Fremlin, has a character who I think is 87, and she seems to be the ultimate victim, someone shunted away. But she isn't.

It's the idea of taking certain domestic tropes and the ways these writers would invert them or find the criminality in them.

And were you specifically looking for stories whose subject was women or women's lives?

I was. But there were a couple of instances where the subject is women who have been pushed aside but who come back, and it's told from a man's perspective.

Many of the stories present the idea that there is a secret world that only the women characters are aware of or understand.

Yes, and in some stories the suspense is subtle, or it seems subtle, but it's actually really scary.

Another fascinating element that comes up is children, which you just don't think of as playing much of a role in crime fiction except as innocent victims to be saved. But these children have more agency.

It's more nuanced than just the bad seed or killer kids, too.

Apart from Patricia Highsmith (whose contribution to this anthology you describe as "a path not taken" in domestic suspense because she'd go on to write mostly about male sociopaths) and Shirley Jackson, whose work is beginning to get a bit of a revival, it sounds like these writers were in danger of being forgotten. Meanwhile, the work of their male counterparts, which wasn't necessarily more widely read or well-regarded in their time, like Jim Thompson or Charles Willeford, has been championed and preserved by reprint houses like Black Lizard or even the Library of America. Why do you think that is?

It's about who gets to decide. Tom Bissell wrote a piece for the Boston Review about the time when he was still an assistant editor at Norton, really young, and he read that Jonathan Franzen essay that introduced him to Paula Fox. He said, "We should publish her," and they said OK. He was astounded to think that, just because of him, "Desperate Characters" was back in print and people were reading it and rightfully proclaiming it a classic. That's a lot of responsibility.

So the champions just weren't there for the women in this anthology?

Yeah, or they were there, but not in the right places to have an effect. You didn't have a Barry Gifford [founder of Black Lizard Press, a mystery publisher] championing Margaret Millar. Eudora Welty wrote a front-page piece for the New York Times Book Review on Ross Macdonald, not on Millar, who was MacDonald's wife.

I've often wondered if this happens because the type of fandom that existed before the Internet was very much about obsessive cataloging and archiving and publishing zines and going to conventions to buy rare editions for one's collection, and other activities that just seem to appeal more to male fans. It's incredible the amount of sheer labor that those cultures of fandom put into preserving the work of the artists they loved. It's why if there's a recording somewhere of an old bluesman, someone will have tracked it down and saved and/or redistributed it. The fans who felt that way about the hard-boiled crime fiction of the postwar period were mostly men and they mostly liked work by other men.

There's definitely something to that. It's not just the genres, though. Sometimes it just takes the right critic in the right place saying, "You've got to read this." Or it takes a really smart biographer to reframe a career. Right now, Ruth Franklin is clearly doing that for Shirley Jackson, by working on a new biography that will assert that Shirley Jackson belongs in the literary canon.

I feel that the only reason Shirley Jackson went underrecognized for so long is that she did not match most people's image of what a great American writer was supposed to be in the middle of the 20th century.

Fortunately, she continued to be read over that time.

You draw a line between these writers and Gillian Flynn's "Gone Girl." An audience for this kind of fiction seems to be coming into its own.

I really think so. This project was already in the works before "Gone Girl" took off, but I have to thank Gillian Flynn for paving the way.

It seems like fandoms run by women have really blossomed with the Internet. They're less about mastery and completism and more about sharing and reinforcing each other's enthusiasms. They're less time-consuming and expensive than the old male-style fandoms, too, yet they can really make a phenomenon out of a book, the way the fan networks created around "Twilight" helped make "The Hunger Games" a hit.

Or the way YA bloggers and video blogging have made John Green a crossover YA star. Young women feel a tremendous kinship with him. There are blog networks and GoodReads. They offer a kinship and emotional connection that fosters the spread of cultural phenomena.

Who else is doing this genre in a contemporary mode?

I was heartened to see that piece about A.S.A Harrison's "The Silent Wife" in the New York Times. Sadly, she can't produce any more novels. I really like what Hallie Ephron is doing. She's totally in that vein. Her most recent novel, "There Was an Old Woman," has a youngish heroine but also a 90-something woman who is nobody's fool and will take care of herself even in the face of a serious threat. And then there's Laura Lippman.

She is so terrific.

And she keeps getting better.

I mean no knock on George Pelecanos or Dennis Lehane, who are excellent, but I don't really see why those crime novelists seem to be regarded with so much more reverence, when Lippmann is, to my mind, consistently more adventurous and interesting. She has something fresh to say about human beings and character and where both intersect with crime and violence in every single book.

She came of age with Pelecanos and Lehane and Michael Connelly and Harlan Coben, all the writers who introduced me to contemporary crime fiction. Those guys all sell spectacularly well and have been written about so much. But with Laura Lippman, there are people still struggling to identify her as more than the woman married to David Simon. Why does that happen? It's the same reason why most of the women writers in "Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives" are out of print but the Library of America has a five-novel volume of David Goodis' work -- which is great…

We both want to go on the record as not begrudging the hard-boiled writers their revival. We're not running them down. We're just asking why women writers who were (or are) doing work that's just as good are not getting the same props.

Exactly. Why does selection bias work that way?

What's the future for domestic suspense?

I think contemporary domestic suspense straddles so many different cultures and genres. Private detective fiction, frankly, became too narrow. It's starting to widen again, and I think women writers are going to help that. Police procedurals, apart from Connelly? It's really hard for me to read about a cop now, especially post-Occupy. With all the surveillance-state stuff, the police stories that I'm most interested in I don't think people are writing. I don't know if they're ready to do it. There's so much weird stuff happening authority-wise that's not properly reflected in fiction.

The downfall of crime fiction is that it can become too fetishized: the whole fedora syndrome, for example. Right now, domestic suspense feels more open, freer.

Shares